Male Sex Work and Society (49 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Of course, men and boys have engaged in sex for commercial and exchange purposes at least since recorded history. Evidence of male sex work dates back to biblical times, and references in ancient images, literature, anecdotes, and even police records verify its longstanding existence around the globe (Dynes, 1990). The male sex industry has not developed in isolation but in relation to other societal developments and new technologies. For example, the pornography industry boomed in the late 19

th

century with the advent of motion pictures, and some of the earliest examples of male-on-male pornographic film date back to the 1920s (Thomas, 2000). In the mid-20

th

century, male sex work was recognized as a facet of sexual subcultures; MSWs and other men who had sex with men were often “lumped into similar categories as ‘sexual deviants,’ occupying similar and overlapping ideological and geographical spaces” (Miller, 2005, p. 1).

th

century with the advent of motion pictures, and some of the earliest examples of male-on-male pornographic film date back to the 1920s (Thomas, 2000). In the mid-20

th

century, male sex work was recognized as a facet of sexual subcultures; MSWs and other men who had sex with men were often “lumped into similar categories as ‘sexual deviants,’ occupying similar and overlapping ideological and geographical spaces” (Miller, 2005, p. 1).

A changing understanding of the male sex industry can be traced in the emergent research literature. In the U.S. context, Bimbi (2007) has suggested that research emerged in four interconnected and overlapping waves that began with a focus on male sex work as a psychiatric disorder in the 1940s; it shifted in the 1950s and 1960s to putting male sex workers into typological groups; in the 1980s and 1990s, the focus became HIV transmission and infection; and, most recently, there is a surge of interest in sex work as work. In the UK context, Whowell and Gaffney (2009, p. 104) offer a framework of understanding that details the ways the identities and bodies of MSWs have been socially (re)constructed through the research discourse in six phases from the late 1970s onward. The first phase, Revolution and Revolt, describes research conducted post-WWII to the late 1970s, which was a period when homosexuality was partially criminalized, homosexual men were considered to be mentally ill, and engaging in sex work was positioned as a type of rebellion. The next body of work emerged in the 1980s and centered on street-based sex workers; it is described under the theme, Retribution and Revenge. Within this theme, MSWs are largely constructed as victims and as experiencing multiple types of chronic social exclusion. Following this, from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, the Repressed and Revived discourse centered on MSWs as “vectors of disease,” as commercial sex at this point was perceived to be an important source of HIV transmission. In the mid-1990s, as research fell under the heading of Reformed and Rebranded, researchers began to diversify and explore other types of sex work beyond street-based engagement. Following this and prior to the publication of the Home Office (2004) consultation, “Paying the Price,” which represented the first substantive engagement with prostitution policy since the 1957 “Wolfenden Report” was published, a new research theme emerged, Rehabilitated and Rescued, which focused on the exploitation of young men engaged in street sex work, with an emphasis on rescue and diversion. Finally, Whowell and Gaffney suggest that the current research discourse positions sex workers as laborers, businesspeople, and those using sex work to explore different types of body work and sexual experiences, and thus they define this theme as Recognized and Rejuvenated (adapted from Whowell & Gaffney, 2009, p. 104). In both the UK and U.S. research contexts, the time periods and associated discourses are overlapping.

This body of work, along with more recent scholarship, provides the context for this chapter, which offers an overview of the debates concerning male sex work in the UK, with a particular focus on specialist service provision, as well as the service needs of male sex workers.

Defining Male Sex Work

The research literature describes sex work practices in various ways, and those engaged in sex work also use varied terminology to describe their practices. For example, Gaffney (2012) reported 12 different responses to a 1996 study that asked 88 MSWs how they defined themselves in the context of their work, including “rent boy,” “tart,” “escort,” and “personal trainer.” Indeed, some men may not actually perceive their practice as sex work, seeing it instead as a way to meet basic needs, explore sexuality, or even as a type of therapeutic practice (Gaffney, 2002; Smith, 2012). Most recently, Atkins (in press) argued that the exchange of intimate practices (which may or may not involve sex) can represent complex relationships between the sex worker and client, and sometimes result in longer term relationships.

1

1

Nevertheless, defining sex work as a form of labor is a much discussed conceptualization in the literature that is sometimes embraced by sex workers themselves, as it “prioritizes attention to the skills, labour, emotional work and physical presentations that the sex worker performs, [and] has been the theoretical underpinning of legal and social changes that have made provisions for legitimate sex work” (Sanders, O’Neill, & Pitcher, 2009, p. 11). Some have argued that the feminist debate about whether sex work is in fact a type of work or is always and inevitably exploitative has largely been superseded by a vast body of empirical research demonstrating that sex work in its varied forms is actually “a more complex reflection of cultural, economic, political and sexual dynamics” (Brents & Hausbeck, 2001, p. 307).

This view reflects the notion that sex work is diverse, that it takes place between a variety of people, in multiple settings, and for a multitude of reasons. Weitzer (2010), for example, presents the polymorphous paradigm, which he suggests “holds that a constellation of occupational arrangements, power relations, and worker experiences exist within the arena of paid sexual services and performances,” and that it is “sensitive to complexities and to the structural conditions resulting in the uneven distribution of agency and subordination” (p. 26). Smith (2012), on the other hand, seeks to understand the experiences of male sex work from a position wherein the “understanding of commercial sex … [is] both historically and culturally contingent and also socially and politically contested” and ultimately is “a set of meanings and practices which have no inherent truth” (pp. 591-592). She draws from poststructuralist work and postcolonial feminist scholarship that “view commercial sex as implicated in but not determined by social structures.” Atkins (in press) goes further, looking at sex work as exchanges of “intimacy” that may or may not involve “sex itself.” He explores how the process of exchange is shaped by “affective energies” in “situations of encounter,” within which what was being “earned was often more than money, [and] what was being sold was more than a time limited service.” Sex as work may be embodied within these conceptual frameworks, but they also offer a more contingent way of understanding the multiple performances, sexualities, and identities associated with sex work.

The social, cultural, and geographical context in which sex work takes place is therefore important in understanding processes of identification, as well as the experiences and needs of male sex workers; as Wilcox and Christmann (2008) note, “the nature of sex work is not necessarily oppressive and … there are different kinds of worker and client experiences which encapsulate varying degrees of victimisation, exploitation, agency and choice” (pp. 119-120). This view is applicable across sectors, of which, as Gaffney (2012) has noted, there are many, ranging from street and opportunistic sex workers (often selling sex to meet basic needs or survive), to erotic dancers and strippers (working in clubs for male and/or female clientele, or working independently for private functions), to “kept boys” (men who exchange sex for a lifestyle and are financially/economically “kept” by another person), and institutional prostitution (sex for exchange in prisons and other institutions), as well as independent and agency escort work (those providing sexual services in an incall or outcall capacity).

As the literature and evidence from practice suggest, men engage in sex work for a range of reasons, and there are multiple routes into the sex industry, including “available labour options, issues of choice, coercion and experiences of violence” (Bryce et al., in press). The context in which sex work takes place, as well as how and between whom, has a significant impact on how individuals experience the work. It is therefore troubling that, over the last 10 years or so, the overwhelming focus of sex work policy and practice in the UK has been limited to the female street market. Although street workers are certainly worthy of considerable attention, off-street workers are a much larger sector of the sex work industry in the UK. Moreover, the common assumption in policy and practice contexts that there are fewer males than females engaged in sex work is, Smith (2012) argues, based on flawed logic:

In empirical terms, the focus on women tends to be justified (if it is justified at all) on the grounds that the “vast majority” of sex workers are female; indeed a huge amount of theoretical weight rests upon the shoulders of this empirical assertion and yet it has never been interrogated empirically. (Rather, the words “vast majority” are uttered and, like a rabbit in a hat, all male and transgender sex workers magically disappear). (p. 590)

The next section explores the gendered policy and practice context in the UK in a little more depth.

Sex Work Policy and Provision of Services: But What about the Men?

2

2

Over the last decade, there has been a flurry of activity relating to national policy approaches to sex work in the UK. In Scotland and Northern Ireland, moves have been made to criminalize the purchase of sex, in a step toward the Nordic Model in which the purchase of sex is prohibited under law but the sale of sex is not. This model, which is informed by a narrow and arguably dangerous radical feminist agenda, favors heterosexist readings of prostitution while ignoring queer embodiments of sex work (Bryce et al., in press; Laing, Smith, & Pilcher, in press).

There had been little activity in the national policy context in England and Wales since the publication of the “Wolfenden Report” in 1957, until the Home Office published “Paying the Price” in 2004, which preceded the new “National Strategy” published in 2006. The “National Strategy” provided guidance from the national level as to how sex work should be managed at the local level.

3

However, after the Coalition government (Conservatives and Liberal Democrats) came into power in 2010, the “National Strategy” was replaced with “A Review of Effective Practice in Responding to Prostitution” (Home Office, 2012), which reflected the broader “localist” agenda of the government in power at the time.

3

However, after the Coalition government (Conservatives and Liberal Democrats) came into power in 2010, the “National Strategy” was replaced with “A Review of Effective Practice in Responding to Prostitution” (Home Office, 2012), which reflected the broader “localist” agenda of the government in power at the time.

FIGURE 11.1

The UK Network of Sex Work Projects guide, “Sorted Men,” geared toward men who sell sex.

Source:

http://www.uknswp.org/resources/

Source:

http://www.uknswp.org/resources/

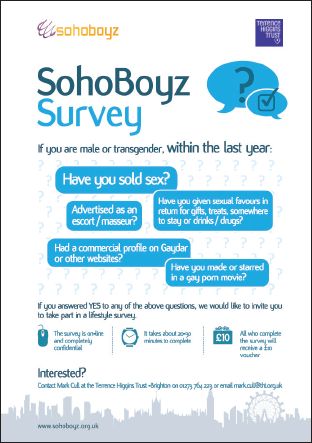

FIGURE 11.2

SohoBoyz, a key service provider for male sex workers in the UK, provides a needs-assessment program.

The journey to the publication of new national policy guidelines is an interesting one, especially when considered through a gendered lens. The focus of the “National Strategy” was almost solely the street-based female sex worker, with little consideration of men and other women working in different spaces (Whowell, 2010). Indeed, the publication noted that the earlier “Paying the Price” provided “scant information on male prostitution” (Home Office, 2006, p. 9). The failure to consider MSWs at this critical stage—especially since the 2003 Sexual Offences Act made all prostitution-related offenses gender neutral—can be considered an oversight at best, a dangerous omission at worst. When referring to male sex workers, the “National Strategy” stated that the government would provide guidance for those offering specialist service provision to male sex workers around support and exit; however, these guidelines were never published. The failure to acknowledge that men and women can be both sex workers and sex buyers reflects the radical feminist ideology and discourse that drove the “National Strategy,” which positioned all prostitution as a form of violence against women and failed to acknowledge evidence of the vastly varied experiences of the men, women, and transgender people involved in the sex industry (Bryce et al., in press). Indeed, the overarching theme of the critical policy literature (see Brooks-Gordon, 2006; Cusick & Berney, 2005; Gaffney, 2007; Soothill & Sanders, 2004) is that the “National Strategy” had a moralistic ideological agenda that sought to challenge and abolish the sex industry, rather than to address more pragmatic issues such as the health, safety, and well-being of sex workers. In contrast, “The Review of Effective Practice” (Home Office, 2012) does consider health and safety, recognizes different methods of supporting sex workers, and has a somewhat more gender-nuanced approach.

Other books

The Truth About You & Me by Amanda Grace

Camino a Roma by Ben Kane

A Wife by Christmas by Callie Hutton

Real As It Gets by ReShonda Tate Billingsley

Weston by Debra Kayn

AdonisinTexas by Calista Fox

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. by Waldman, Adelle

White Wolf by David Gemmell

Season of Secrets by Sally Nicholls

Cain's Crusaders by T.R. Harris