Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks (5 page)

Read Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks Online

Authors: Ken Jennings

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Technology & Engineering, #Reference, #Atlases, #Cartography, #Human Geography, #Atlases & Gazetteers, #Trivia

Not all feats of spatial memory are long-distance migrations straight out of Walt Disney movies.

The frillfin goby

is a small tropical fish that’s usually found in rocky pools along the Atlantic shore. When threatened in a tide pool, either by a predator or by falling water levels, it has a remarkable defense mechanism: it escapes by shooting itself up into the air, like James Bond from an Aston Martin ejector seat. If you ever had a suicidal goldfish as a child, you know that accurate jumping isn’t always a fish specialty, but the goby always jumps straight into another (safer) pool. Sometimes it makes up to six consecutive pool hops until it arrives in open water. Obviously the fish can’t see out of its own pool, so how does it make these leaps of faith? It plans ahead. It takes advantage of every high tide to explore its surroundings so it knows—and remembers—where the safest spots are likely to be once the tide goes out.

But just because an animal can perform an impressive bit of way-finding doesn’t mean it’s relying on a sophisticated cognitive map. The clarinetist’s shearwater, for example, was crossing territory it had never seen before, the North Atlantic. It was obviously flying on instinct, not a mental map from past experience. We now know that many migrating birds rely on the position of the sun as a compass, as well as the sights and even smells of habitats along the way. Baby turtles are sensitive to tiny variations in the earth’s magnetic field; you can get a loggerhead turtle to change directions in a swimming pool by placing powerful magnets nearby.

*

We humans use many of the same tools to orient ourselves that animals do; we’re just not as good at them. We don’t have magnetite in our beaks like homing pigeons do, but otherwise the principles are the same. Take my family’s recent trip to Washington, D.C.

• On our first day there, we walked from the Metro to the Air and Space Museum and then to the Natural History Museum. To get back to the Metro, we didn’t retrace our steps through both museums. We mentally gauged the distances and directions we’d traveled and set out to walk directly toward the Metro. Animal species from fiddler crabs to ground squirrels can do something analogous, only with much greater accuracy. An ant, for example, can wander around aimlessly for two hundred meters (at human scale, the equivalent of running

a marathon) and then, from any point, return in a straight line to exactly where it started. This is called “path integration,” and it’s a crucial ability for foraging animals, which wander over a vast territory looking for food but need to be able to return directly to the nest as soon as they find enough to eat.

• Every time we double-checked our location by looking to see where we were relative to the Tidal Basin or the Washington Monument, we were mimicking another common animal trick: the use of landmarks. Many species of jays and nutcrackers, for example, are “scatter hoarders,” meaning that they store little food caches in as many as eighty thousand locations over a single winter. These birds rely heavily on landmarks to recover their hidden goodies; if nearby visual cues are tampered with, the food will be lost forever.

• We even used some rudimentary celestial navigation on our trip, as the Manx shearwater does. In which direction is the late-afternoon sun? All right, then, the White House is that way.

By the end of the day, we had the lay of the land down pretty well; even Mindy could find her way between any two monuments we’d visited without resorting to landmarks or a sun compass. It’s hard to be sure which animals can do the same. We can’t exactly ask them. The current consensus is that mammals, and possibly even some insects, like honeybees, can think in terms of maplike models. In one experiment that’s been repeated with

both dogs and chimpanzees

, an animal accompanies the researcher as food is hidden at various points within an enclosure. The animal is taken to a food cache, then back to a starting point, then on to another food cache, then back to the start, and so on. When the animal is released, it’s vastly more successful at locating the food than are other subjects that didn’t get the walking tour, of course. But, more suggestively, the dog or chimp won’t just retrace the researcher’s steps between the food and “home.” It will actually invent efficient new routes to circle through nearby food caches without ever having to revisit the starting point.

“Every species is good in its own niche” when it comes to navigation, says David Uttal. “We’re not at the top of some evolutionary ladder.” This probably goes without saying, given that a Chinook salmon

can swim a thousand miles upstream to the place it was born just by following its nose, whereas a human often struggles to find a car in a parking lot after ten minutes in a grocery store. “But what we have that no other species has is culture. We can share information, and that gives us an amazing flexibility.”

That’s where mapmaking comes in. When humans take information from mental maps and put it down on paper (or a cave wall or clay tablet), the game is fundamentally changed. Sure, a honeybee can share geographic information with his hive by doing a little dance, but according to Karl von Frisch, who won a Nobel Prize for translating the bee dance, it has only three components: the direction of the food source relative to the sun, its distance, and its quality. The maps we make for other humans are much more versatile. The same map of southern Africa that I used as a kid to imagine Tarzan-style adventures could be used by an environmentalist to study land use, a tourist to plan a safari, or a military strategist to plan a coup or invasion. It has thousands of potential routes on it, not just one.

There are plenty of possible ways you could express to others the geographical information in your mental map: a written description, gestures, song lyrics, puppet theater. But maps turn out to be an enormously intuitive, compact, and compelling way to communicate that information. To emphasize that they’re not “innate” seems to stop just short of saying that maps are an accident, the product of dozens of arbitrary cultural decisions. I think that misses the point. Just because maps aren’t innate doesn’t mean that they’re not optimal, or even inevitable.

Cast your mind back, for a moment, to the middle of the last century. Today, orbital imagery is everywhere and we take it for granted, but before the space race began, no Earthling had ever seen our home planet from high above—that is, from the viewpoint of a large-area map. If you look at science-fiction movies and comics from that era, you’ll see that the Earth is almost always depicted like the Universal logo or a schoolroom globe:

without any cloud cover at all

. We had no idea what we looked like from outside ourselves! As a species, we were the equivalent of Dave Chappelle’s famous comedy sketch character: the blind Klansman who doesn’t know he’s black.

But when John Glenn became the first man to orbit the earth

in 1962, he looked down in surprise and told the Bermuda tracking station, “I can see the whole state of Florida just

laid out like a map

.”

*

Think about what that says about the fidelity of maps: seeing the real thing for the first time, the first thing that occurred to Glenn was to compare it to its map representation. In that one sentence, he validated that maps had been getting something fundamentally

right

about Florida for centuries. That makes me think that we shortchange maps by calling them mere cultural conventions. Sure, some of the specifics that we take for granted might be arbitrary—the angle of view, dotted lines for roads, blue ink for water, and so on—but not the fact that we as a species rely heavily on pictorial representations of the surface of our world. They’re critical to the way we think. If maps didn’t exist, it would be necessary to invent them.

That’s also demonstrated in our compulsion to turn

everything

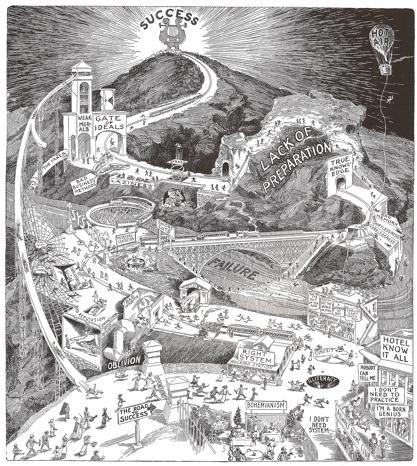

—not just spatial data—into map form. For centuries illustrators have been drawing

allegorical maps

, which schizophrenically join the beauty and detail of classic illustration with all the bag-of-hammers subtlety of a 1980s after-school special. In the 1700s, it was popular to draw romance as a nautical chart: watch out for the Rocks of Jealousy and the Shoals of Perplexity on your way to the Land of Matrimony! Unlucky sailors would wind up marooned at Bachelor’s Fort on the unfortunately named Gulf of Self Love. The Prohibition era gave us railroad maps of temperance, in which the Great Destruction Route might seem like fun as you’re chugging through Cigaretteville or Rum Jug Lake but then quickly diverts you through the States of Bondage, Depravity, and Darkness. One of the most popular illustrations of the 1910s was “The Road to Success,” depicting a snare-laden road through Bad Habits, Vices, and the carousel of Conceit, in which only the tunnel of True Knowledge leads successfully through Lack of Preparation mountain and inside the Gate of Ideals. A recent Matt Groening cartoon updates this map for the twenty-first century. Now the road takes aspirants past the meadow of Parental Discouragement and the River of Unsold Screenplays, inside the House of Wrinkles, and up into the Tower of Fleeting Fame . . . which unfortunately leads straight to a long slide marked “Disappointing Sales of Second Album, Novel, Play or Film Followed by the Long, Long Slide Back to the Bottom

*

(

*

Drug Addiction Optional).”

The most popular allegorical map ever drawn.

Watch out for the slide of Weak Morals!

Why this urge to turn every facet of life into a mappable journey? Hell, why see life itself as a journey to Heaven, the way medieval Christian maps always did? That whole metaphor isn’t in the Bible anywhere. (Well, that’s not strictly true. I’m sure there are lots of verses about walking in righteous paths and so on. But nowhere, as far as I know, does God tell the children of Israel, “Verily I say unto you that life is a highway. Yea, thou shalt ride it, even all the night long.”)

For a long time I blamed writers like John Bunyan and Dante for this allegorical form of cartacacoethes. Desperate to extract a story-line from a possibly dreary and didactic subject—the struggle to live a life worthy of Heaven—they seized on a quest narrative, a “pilgrim’s progress,” and mapmakers were quick to follow suit.

*

I wonder: how would history be different if Bunyan or Dante had chosen to represent life not as a linear journey through a geographic territory but as something a little more holistic—a library, say? Or a buffet? (

Pilgrim’s Potluck

!) What would Western civilization be like in that alternate universe? Would we value different things, set different goals for ourselves, if the governing geographic metaphor of our culture were replaced by something else—recipes instead of maps, cookbooks instead of atlases? Would shallow celebrities still tell interviewers they were “in a good place right now”? Or would they say things like “I’m at the waffle bar right now, Oprah”? (“You eat, girl!” Respectful audience applause.)

Maybe, but I think there would still be people like me who would

see everything through the filter of geography, because of the spatial way our brains are wired. The sense of place is just too important to us. When people talk about their experiences with the defining news stories of their generation (the Kennedy assassination, the moon landing, the Berlin Wall, 9/11), they always frame them as where-we-were-when-we-heard. I was in the kitchen, I was in gym class, I was driving to work. It’s not relevant to the

Challenger

explosion in any way that I was in my elementary school cafeteria when I heard about it, but that’s still how I remember the event and tell it to others. Naming the place makes us feel connected, situated in the story.

And maps are just too convenient and too tempting a way to understand place. There’s a tension in them. Almost every map, whether of a shopping mall, a city, or a continent, will show us two kinds of places: places where we’ve been and places we’ve never been. The nearby and the faraway exist together in the same frame, our world undeniably connected to the new and unexpected. We can understand, at a glance, our place in the universe, our potential to go and see new things, and the way to get back home afterward.

When my family moved overseas in 1982 so my dad could work at a Korean law firm, I missed my imprinted habitat of western Washington State. In many ways, South Korea was the polar opposite of Seattle: hot in the summer, dry in the winter, crunchy cicadas underfoot instead of slimy slugs. The Seoul air was so polluted that I developed a convincing smoker’s hack at the tender age of eight. Before the end of World War II, Korea had been a Japanese colony, and the peninsula had been stripped of forests to help fuel Japan’s massive industrial and military expansion. The neat rows of spindly pine trees assiduously replanted by the Korean government seemed like soulless counterfeits when compared to the dense, majestic forests of the Pacific Northwest.