Master Thieves (4 page)

Authors: Stephen Kurkjian

When they got to Rossetti's house Royce instructed his passenger to remove his blindfold. By this time he was getting comfortable, and knew that after the blindfolded drive he had the stranger's full attention. “You know, I'm planning another score that might interest you,” Royce said. “The artwork there makes this look like small potatoes.” Royce handed over a guidebook to the Gardner Museum.

“Me and the old man have a plan,” Royce boasted, nodding toward the book. “Anything catch your eye?”

“Are you kidding?” the stranger said with a laugh, flipping through the guidebook. “Let's see what you've got first. Let's see how this goes.”

Royce led the group to the backyard, to a door not easily seen from the street. That's when he noticed the stranger's shoes.

”Did you see those shoes? Look at that shine,” Royce whispered to the elder Rossetti, who blew off Royce's concerns.

“Let's do this,” Ralph said, and the meeting went forward.

They showed the stranger all eleven pieces from the score at the Newton home.

“This is nice, quality stuff,” the stranger said. “$50,000 for everything, right? I don't have time to raise that kind of cash. How about $10,000 for the DalÃs?”

Three prints for $10k? Royce nodded approvingly to the Rossettis.

A meeting was scheduled, but the stranger kept putting Royce off. Before long Royce gave up on him. “He doesn't have the dough,” Royce told Ralph Rossetti.

Then, in late August, six months after their initial meeting, the stranger called Royce.

“Let's make a deal,” he said.

As he continued to wait for an opportunity to cash in his big score, Royce finally heard the magic words from his fence.

“Where can we meet?” the stranger asked. “I've got a buyer for the stuff myself, and I want to do this deal as quickly as possible.”

“Stevie will meet you late tomorrow afternoon,” Royce said. “East Boston. Outside the entrance to the Sumner Tunnel.”

The next day, Royce and Ralph Rossetti sat in Royce's car about a block away from the arranged site for the meeting, a tunnel that carries cars to and from downtown Boston and Logan Airport. But before the younger Rossetti even arrived on

the scene with three of the Dalà prints, a swarm of FBI agents descended on Royce's car and arrested him and the elder Rossetti. They also seized three of the paintings stolen from the Newton home: one lithograph signed by Chagall and two signed by DalÃ.

While Stevie Rossetti was able to elude capture, Royce and Ralph Rossetti were arrested and arraigned on multiple theft charges in Middlesex County Superior Court. They made bail, but Royce returned to court less than a year later to face the charges. He knew he had little recourse but to plead to the break-in at the Newton house. But he had an offer to make to the prosecutors.

“If you drop the charges against Ralph, I'll tell you where you can find the rest of the score,” he told prosecutors.

The deal was struck, though nothing was said about it when Royce appeared in court. Less than a month later police announced a raid of a North Shore motel during which they'd recovered the valuable paintings and prints that had been stolen from the Newton home. Neither Royce's nor Rossetti's names were made public as being involved in the paintings' recovery.

______________________

I first met Louis Royce

in a private room at a Massachusetts state prison, in a section where inmates could meet with their friends or lawyers. He was in the final months of the seventeen-year sentence for pleading guilty to masterminding a scheme to kidnap and hold for ransom a well-to-do Boston restaurant owner.

“This is the third long bid I've done since the early '70s,” he told me, estimating that he had spent about five years during the past four decades on the street, with two of those years as an escapee from federal custody.

In fact, Royce's criminal record shows that even as a twelve-year-old he was being arrested by Boston police. But those early run-ins with the law, according to his record for being a “stubborn child,” soon turned more serious as he became adept at larceny and breaking and entering.

Despite the grimness of his past, Royce was upbeat when we met and I told him that I wanted his help in figuring out the Gardner case. Over the next several months we met more than a dozen times and I came to appreciate how important Royce's experiences were to solving the case. Royce swore he did not know who was responsible for the theft; he had been in prison when it had taken place. But I knew that if I could get him talking, all these years later, he would surely tell me whom he'd told about how vulnerable the museum was to a major theft, not to mention the details of his elaborate plan, and that in turn might help me to determine who pulled it off.

Royce was blunt about his motive. He had two reasons for wanting to see the case solved.

“I figure they still owe me my 15 percent,” he said. Under the norms of the criminal life, the person who learns of a potential score, or hatches the plan for it, and passes it on to others, is due 15 percent of the profits of the theft, depending on the tipster's clout with the actual thieves. “As I see it, with the way it works in my world, someone owes me a lot of money.”

“You find out who did it,” Royce said. “I'll make my case with them.”

Also, Royce said, regardless of who had ordered it and why, the specific purpose of the theft way back in 1990 had long since passed. “Maybe they [the paintings] were taken to get someone out of jail, but that obviously hasn't happened. So they're just laying somewhere now, unseen and unappreciated. They should be back with the museum now.”

Before I spoke to Royce I knew I had to check to make certain of his bona fides. I needed to be sure he had indeed been a master thief who had studied how to rob the Gardner

Museum and that he was a trusted member of one of Boston's most aggressive underworld gangs and had brought the secret of how to rob the museum into that mob.

Soon I had the testament of the FBI's leading undercover agent in New England during the 1970s and 1980s.

“He was the best thief I'd ever seen,” FBI special agent William Butchka told me, without hesitation. “He was clever, and he'd study a job for however long it took to figure out the best way of pulling it off successfully.”

As for the possibility that the plan to rob the Gardner Museum had originated with Royce, Butchka said, “I had never heard anyone talking about it before him. The next time I heard about the museum after that, it had just been robbed.”

I had been reporting on the Gardner theft for the

Boston Globe

since 1997, and getting Royce to talk seemed a tremendous advantage. Confidential files attested to his having cased the museum for a major robbery and, since this was the first time he had spoken about it, I felt confident he could provide the link that would lead to a breakthrough.

Unlike the FBI, whose strategy for finding the stolen artwork had evolved into a game of waiting for someone to call to make a deal or the Hail Mary of waiting for an anonymous tip, Royce offered a different path. The key to recovering the artwork lay with the crew who had stolen it, and Royce surely knew who they were.

Still, I wondered if it were possible that this eighth-grade dropout, who had spent most of his adult years behind bars, could hold the secret to this infamous case.

______________________

While with the Rossetti gang

in the early 1980s, Royce says, he made several visits to the Gardner Museum. He had not

been back to the museum since his boyhood, but now it was more than a warm place to spend the night. During his ensuing years as a criminal, Royce had hatched a plan to rob the Gardner of some of its most precious artifacts.

Royce told me about a fellow gangster who had taken part in the theft of a valuable Rembrandt from a Worcester museum in the 1970s. Royce had been impressed with the favorable buzz the heist had garnered in the criminal underworld.

Although a guard had been shot in the Worcester robbery, Royce was convinced that the security at the Gardner was so lax that he could pull in a huge score, and best of all, without any violence.

Royce wasn't looking to hit the Gardner to secure the prison release of an associate or strike a plea bargain deal, as had become the custom in the gangland underworld. Instead, he had riches in mind. Royce and his fellow gangsters put the word out, seeking a commission from a wealthy art collector connected to the underworld. Then he made a detailed study of the museum's security system and decided that, while a number of approaches for breaking into the building could be made, the easiest time to hit the museum was at night. The museum held chamber music concerts on Tuesday evenings that were lightly attended and overseen by only one or two guards. With Rossetti in tow, Royce planned to walk into the concerts and ignite several smoke bombs. In the ensuing chaos, they intended to rush to the galleries where the paintings they planned to steal were hanging and make as fast a getaway as they could manage.

Of course, once inside, Royce planned to find a way of getting his hands on the crucifix scene painted by Raphael in 1504, captured in a rich golden frame,

Lamentation Over the Dead Christ

, purchased by Mrs. Gardner in 1900 just as she was moving forward with constructing her museum in Boston's Fens neighborhood.

Royce showed the score to Richard Devlin, who was immediately keen on the plan. Devlin knew from his brother and a former neighborhood accomplice, both of whom had been arrested for trying to fence stolen paintings in Florida in the late '70s, the value of rare masterpieces. He was more than willing to accompany Royce when he scoped out the Gardner.

As fate would have it, one night while driving past a construction site near the museum, the pair noticed several pieces of heavy equipment apparently being used in a renovation job. Who needed police uniforms and smoke bombs when you had a cherry-picker truck left right there for the taking?

In an instant Royce decided this was the simplest way for him to grab the piece he had coveted for so long. He knew the Raphael crucifix scene was right there by the second-floor window, so the two men simply “borrowed” the man-lift.

“This is perfect,” Royce thought as he drove the piece of equipment the three miles to the museum. At the corner of the Fens and Palace Road, right in front of the Gardner, the pair made it seem that they were members of an emergency utility crew and set up orange cones around a nearby. . . . With Devlin providing lookout, Royce swung the bucket of the cherry-picker into place, close to the museum's second-floor windows.

“I was within fifteen feet of it, but I could see the damned window was locked,” Royce remembers. “I considered breaking the glass, but I knew it would have set off an alarm. And there was no way we'd be able to get away in time with that piece of equipment. I waved off Richie [Devlin], and that was it.” Thankfully, keeping the windows locked was one security precaution the museum always maintained.

Although they may not have known about the incident with the cherry-picker, the FBI knew of Royce's interest in robbing the Gardner from their undercover encounter with him and the Rossettis trying to sell the valuable prints they had stolen from the Newton home.

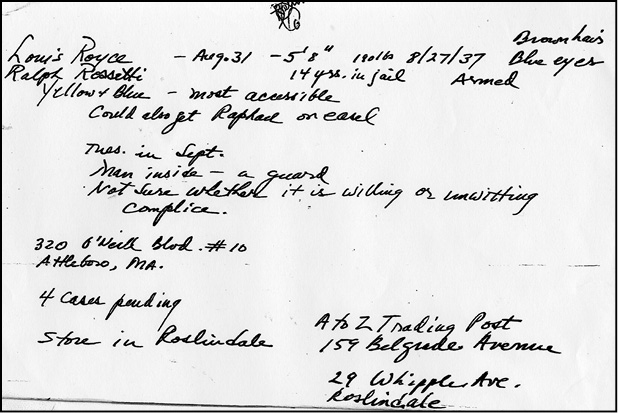

Notes taken by the Gardner Museum's deputy director during a confidential meeting with FBI agents on September 23, 1981, held to inform the museum that it was in danger of being robbed by master thief Louis Royce and Ralph Rossetti, head of an East Boston gang.

Within days of recovering the artwork stolen from the Newton residence, the FBI had reached out to officials at the Gardner with a message.

“You're going to be hit.”

“Lyle, we've been contacted by the FBI and two agents want to come in to see us,” said a 1981 note from Linda Hewitt, the Gardner Museum's deputy director, to Lyle Grindle, its security director.

The next week, on September 23, 1981, FBI special agent Edward Clark and a second agent were ushered into the museum's small first-floor library. Around a small wooden table, they shook hands with the three people who were most responsible for the museum's safety: Grindle; Roland “Bump” Hadley, the museum's director; and Hewitt.

Clark, a textbook example of an FBI agent, trim with sharp features, a crisp suit, and an almost military demeanor, didn't

waste any time with pleasantries. Instead he opened the meeting candidly.

“You've got a problem, my friends. Some people have found a hole in your security system.”

The Gardner staff, not used to such brusque talk, especially from law enforcement, bristled.

“The FBI's Boston office has come in contact with men who have been working with a gang from East Boston,” Clark went on, in a formal, affected FBI manner the staff recognized from television and movies. “They're intent on breaking in and robbing your museum.”

Clark let the words hang there for a moment to make sure they sank in. They did. The museum had never suffered a major theft as far as any of the three Gardner officials in the room knew. The only known loss had taken place more than a decade before when someone stole a miniature Rembrandt self-portrait sketch from its easel in the Dutch Room. The guard's attention had been diverted when another person smashed a bag full of lightbulbs on the marbled floors. Who stole it or why was never determined, but the etching returned just as mysteriously a few months later when a New York gallery owner was approached by a third party to buy it and saw from printing on its back that it belonged to the Gardner Museum.