Memories of the Future (15 page)

Read Memories of the Future Online

Authors: Robert F. Young

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Anthologies, #short stories, #Anthologies & Short Stories

But the roots can be traced back farther yet. They can be traced back to the days when he himself was a Jonah and killed spacewhales, ostensibly for a living but actually out of revenge for his having been temporarily blinded by one, and scarred for life. Killed them, till one day he saw his face in one and could kill them no longer.

The complexity of problems is no new thing under the suns, but the complexity of this one is nevertheless unique. Ciely Bleu, at odds with the proletariat society she grew up in on Renascence (

a

Andromedae IX) and whose members she scornfully calls the “

haute bourgeoisie

” because of their middle-class values and because they put on “parvenu airs,” stole a star eel that was undergoing experimental conversion out of the Renascence Orbital Shipyards (where her father is employed as a converter) to keep it from being enslaved. Three weeks later (Renascence time), the eel, which she had named “Pasha” and which she loved, affixed itself to Starfinder’s whale and began absorbing its 2-omicron-vii lifeblood. Starfinder boarded the eel, conned Ciely into returning with him to the whale, where he talked her into calling the eel off. The whale, acting out of instinct, promptly rammed the eel, destroying it. Starfinder should have anticipated this, but he didn’t.

The eel, despite its gargantuan size, was Ciely’s pet, and its death overwhelmed her. The whale, contrite, substituted itself.

it “said,” indicating that she and Starfinder and itself would henceforth be three comrades in the Sea of and

and . The antidote worked, and she has come to love “Charles” as much as she loved “Pasha.” It is now up to Starfinder to return her to her

. The antidote worked, and she has come to love “Charles” as much as she loved “Pasha.” It is now up to Starfinder to return her to her

“haute bourgeoisie”

parents.

Well, this doesn’t seem like much of a problem. There will be tears involved, of course, and sad farewells; but eventually Ciely will forget Starfinder and the whale and come to love her

“haute bourgeoisie”

parents, however much she may think she despises them. But wait: There are financial and legal complications to contend with. The star eel she stole was the property of Renascence’s Orbital Shipyards (OrbShipCo), and, at a conservative estimate, was worth in the neighborhood of $10,000,000,000. It is doubtful that Renascence law will allow a twelve-year-old girl to be prosecuted for grand larceny; nevertheless, someone is going to have to pay the $10,000,000,000 back.

Starfinder is as poor as a church-mouse. He doesn’t even own his own whaleship—at least not legally.

No doubt Ciely’s parents are moderately well-to-do and have money in the bank in the city of Kirth, which is the New Bedford of the star-eel industry and the headquarters of OrbShipCo. But how are they going to raise $10,000,000,000? How, for that matter, if their daughter can be prosecuted, are they going to raise enough to cover the fee of a lawyer crafty enough to keep her out of jail?

Problem? This is no problem. This is a brick wall. A four-dimensional brick wall that slams against you just as hard when you try to climb over it or to go around it or to burrow under it as it does when you try to barge right through it.

But fortunately Starfinder has in his possession a four-dimensional sledge hammer in the form of a whale.

He turns off the timescreen, retires to his cabin and has the wardrobizer outfit him in nondescript apparel that will pass uncommented upon where and when he is going. From a secret drawer of his desk he removes a pair of telekinetic dice and slips them into one of the pockets of his nondescript coat. Into another pocket he slips an ostentatious bauble that can easily be converted into legal tender. Then he leaves the cabin, makes his way forward and ascends the companionway to the bridge. There, via the computer, he programs the whale to surface five hundred miles off the shores of Kirth (well beyond the orbiting dead star-eels and the conversion docks and the space stations that constitute the orbital shipyards) at a temporal level when Kirth was a small town and the star-eel industry was still in its embryonic stage, and he post-programs the whale to dive the moment he departs in the lifeboat and to resurface one Renascence month later at a corresponding point in space. Then he girds himself and descends to the boat-bay. He has a busy “night” before him.

* * *

“You look bushed, Starfinder,” Ciely says over her cereal. “Didn’t you sleep well last night?”

Starfinder fortifies himself with a second cup of coffee and dials an order of toast and scrambled synthi-eggs. In the galley viewscreen,

a

Andromedae hangs like a dazzling Christmas-tree ornament from the black branches of the fir of space. In the foreground, hogging most of the screen, Renascence turns imperceptibly on its axis, its dayside green-gold, and tinged with blue. The orbital shipyards, visible only on the nightside, bring to mind a moving semicircle of twinkling trinkets.

Where did those little crow’s feet at the corners of your eyes come from?” Ciely asks, when Starfinder makes no reply. “They weren’t there last night.”

“I didn’t know there were any crow’s feet at the corners of my eyes.”

“Well there are.”

Starfinder doesn’t argue. Instead, he tackles his order of toast and scrambled synthi-eggs. He is wearing his captain’s uniform. It is white, with gold piping. The left side of the coat front is hung with seven rows of multi-colored ribbons, to each of which is attached a gleaming, meaningless medal. The epaulets match, in both color and design, the décor on the fore-piece of the white hat, which rests on the table near his elbow, and bear a strong resemblance to the scrambled synthi-eggs he is eating. The white trousers have triple creases and are tucked neatly into black, synthi-leather boots that are so highly polished you can see your face in them. The uniform came with the whale.

Ciely is staring at the viewscreen. Her abbreviated khaki dress, faded from many washings, gives evidence from its tightness of the weight she has gained during her sojourn in the belly of the whale. “Are you going to come and see me after they put me in jail, Starfinder?”

“No one’s going to put you in jail, Ciely. Everything’s been taken care of.”

She doesn’t seem to hear him. “I’ll get life at least. And my mother and father will gloat. ‘Steal a ten-billion-dollar star-eel, will you?’ my father will say. ‘Well, you’re getting your just desserts.’ ”

“But, Ciely, you’re not going to jail.”

“The

haute bourgeoisie

are like that, you know. They don’t care about their children. All they care about is time-and-a-half on Saturdays and double-time on Sundays.”

“Ciely, listen—”

“My father is so hungry he works every Sunday they let him. He’s a brown-noser too. Every Christmas he gives the shift leader a case of Scotch.”

“Ciely, I don’t have any choice. I

have

to take you home.”

“I know. My debt to society must be paid.”

“It has nothing to do with your debt to society. Anyway, there’s no longer any such debt. But I still have to take you home. You belong with your parents, with young people your own age. You can’t grow up in a spacewhale with no one to keep you company but an old man of thirty-three.”

She begins to cry. The handle of her spoon protrudes forlornly from her forgotten bowl of cereal. Her glass of synthi-milk stands untouched by the synthi-sugar bowl.

Starfinder is a great hand with children in distress. He sits there woodenly in his dazzling captain’s uniform, like a bemedaled bump on a log. Oh, he is a great hand with them, all right.

It is up to the whale to save the day. With its usual

savoir-faire

, it does so:

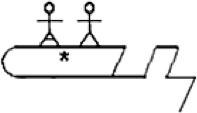

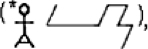

it says, signifying, by the juxtaposition of itself (*), Ciely ( ), and

), and (space-time), that they will always be comrades no matter how far they may drift apart.

(space-time), that they will always be comrades no matter how far they may drift apart.

“I know, Charles,” Ciely whispers. I know we will.” She dries her eyes with her napkin and stands up. “I’m ready, Starfinder.” And then,

I love you, Charles. Goodbye.

* * *

The lifeboat lands in a big back yard beside an in-ground swimming pool. It is night, and there is the scent of new-mown grass.

“Where are we, Starfinder? Whose house is that?”

“Mine,” Starfinder answers.

She stares at it. It is three-storied, cupolaed, multiwindowed. Behind it is a big double garage. A driveway winds around the house and down a grassy slope and joins hands with a highway. There are no other houses for miles around—only fields and trees. In the distance, the lights of a large city can be seen.