Memories of the Future (18 page)

Read Memories of the Future Online

Authors: Robert F. Young

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Anthologies, #short stories, #Anthologies & Short Stories

That’s all behind us now, whale. Now, it’s just you and me. Two comrades instead of three. De-orbit!

You can’t leave me in the lurch, whale! Remember our pact!

!!!

!!!

Damn it, whale! Do you want me to kidnap her?

Silence.

Even if I dared, she needs more than just a father. She needs a mother, too.

Starfinder throws his captain’s hat on the deck. Not only is he furious, his “duodenal ulcer” is killing him.

All right, whale, this is the end! It so happens that I have a house in the country down below and that I happen to own stock in half the major corporations on Renascence and. . . .

And then he remembers that he deeded his house in the country to the Bleus and that he liquidated all his stock to buy the star eel and to establish a trust fund for Ciely and that he is as poor as he was before he went pastbacking—to wit, as a church mouse.

Moreover, without the whale’s cooperation, he can’t amass another fortune.

Would he if he could?

Would he, if he could, buy another house in the country and settle down for the rest of his life among the

“haute bourgeoisie”

?

He would sooner settle down among the Great Apes of Tau Ceti III.

Ciely has no option. At least not until she comes of age.

By then, it may well be too late. By then, she may very well be a Great Ape herself.

It is true that her parents aren’t really Great Apes. But they might just as well be.

Why did he blind himself to the glaring truth? Why did he refuse to face the inexorable fact that they do not give a damn about her, never have and never will?

Because the alternative was kidnapping her?

Hardly. He already has two crimes lying on his doorstep. There is sufficient room for one more.

Because there isn’t enough room for two people in the whale?

Hardly. There is enough room in the whale for a whole girl’s school.

Because living in the whale, in space, in time, would deprive Ciely of a proper education?

Hardly. Not with the entire past, with its wealth of music, paintings, sculptures, literature, drama, philosophy, and science at her very fingertips.

Because she would be deprived of the company of young people?

Hardly. He could set up housekeeping in a place-time of her choice, and she could attend school and become part of a peer group and remain a part for as long as she chose. All he would need would be money, and with the whale’s cooperation he could amass another fortune anytime, anywhen.

A panorama of what he and the whale can do for her appears before his eyes, dazzling him. It has been there all along, but up till now he has refused to look at it.

Why?

Why did he pretend it wasn’t there? Why did he pretend that in stranding Ciely among the

“haute bourgeoisie”

he was acting in her own best interests?

The answer, when it comes, punctures his ego like a pin piercing a balloon.

He acted as he did because he knew that the freedom he stole when he stole the whale was in jeopardy. Because, whenever he balanced that freedom against the love of a little girl, he always put his thumb on the scales. Free, unfettered, he was afraid to cross his Red Sea, his Hellespont, his Alps, his Rubicon, his Atlantic, and his Isthmus.

Well, he is afraid no more.

* * *

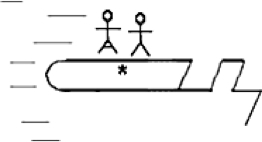

He lands the lifeboat in the Bleus’ front yard, knocking down the pretentious cast-aluminum sign and demolishing the rest of the flowerbed. He pounds on the front door so hard he nearly knocks the house down, and when a startled Mrs. Bleu opens it, he rushes through the living room without difficulty. She is fast asleep on her narrow bed. Her pillow is wet with tears. He picks her up, grabs an armful of dresses out of a nearby closet and carries her in her night clothes back down the stairs and through the living room and out onto the porch and down the steps and across the ruined flowerbed to the lifeboat.

Behind him, a half-awake Mr. Bleu bellows, “Bring back my dotter, you space-bum, you!”

“Kidnapper!” screams Mrs. Bleu.

Somehow, they sound like actors in a play.

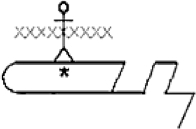

Starfinder lofts the lifeboat. Miraculously, his “duodenal ulcer” has healed. Ciely doesn’t come fully awake till they are halfway to heaven. “Starfinder, you came back!” Presently the whale shows above them, a gigantic silhouette against the stars. Starfinder docks the boat and they make their way together to the bridge. Now

will you de-orbit, whale?

Now

will you dive?

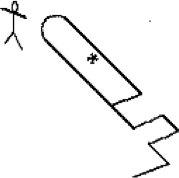

There is a great crepitation as 2-omicron-vii energy fills the drive tissue. A faint creaking of bulkheads as the whale girds itself for the de-orbital thrust. And a rebus thrown in for good measure:

The whale breaks free. A moment later, it dives.

“I think,” says Starfinder,

pere et mere

, leading the way to the lounge, “that we might have a glass of orange pop before we turn in. And maybe look in on ‘Ba’ and see how she’s doing with her

Sonnets

these fine days.”

“observes” the whale.

“observes” the whale.

“Oh,

you!

” says Ciely Bleu.

A Drink of Darkness

“Y

OU’RE WALKING DOWN FOOL’S STREET,”

Laura used to say when he was drinking, and she had been right. He had known even then that she was right, but knowing had made no difference; he had simply laughed at her fears and gone on walking down it, till finally he stumbled and fell. Then, for a long time, he stayed away, and if he had stayed away long enough he would have been all right; but one night he began walking down it again—and met the girl. It was inevitable that on Fool’s Street there should be women as well as wine.

He had walked down it many times since in many different towns, and now he was walking down it once again in yet another town. Fool’s Street never changed no matter where you went, and this one was no different from the others. The same skeletonic signs bled beer names in naked windows; the same winos sat in doorways nursing muscatel; the same drunk tank awaited you when at last your reeling footsteps failed. And if the sky was darker than usual, it was only because of the rain which had begun falling early that morning and which had been falling steadily ever since.

Chris went into another bar, laid down his last quarter, and ordered wine. At first he did not see the man who came in a moment later and stood beside him. There was a raging rawness in him such as even he had never known before, and the wine he had thus far drunk had merely served to aggravate it. Eagerly he drained the glass which the bartender filled and set before him. Reluctantly he turned to leave. He saw the man then.

The man was gaunt—so gaunt that he seemed taller than he actually was. His thin-featured face was pale, and his dark eyes seemed beset by unimaginable pain. His hair was brown and badly in need of cutting. There was a strange statuesqueness about him—an odd sense of immobility. Raindrops iridesced like tiny jewels on his gray trench coat, dripped sporadically from his black hat. “Good evening,” he said. “May I offer you a drink?”

For an agonizing moment Chris saw himself through the other’s eyes—saw his thin, sensitive face with its intricate networks of ruptured capillaries; his gray rain-plastered hair; his ragged rain-soaked overcoat; his cracked rain-sodden shoes—and the image was so vivid that it shocked him into speechlessness. But only briefly; then the rawness intervened. “Sure I’ll have a drink,” he said, and tapped his glass upon the bar.

“Not here,” the gaunt man said. “Come with me.”

Chris followed him out into the rain, the rawness rampant now. He staggered, and the gaunt man took his arm. “It’s only a little way,” the gaunt man said. “Into this alley . . . now down this flight of stairs.”

It was a long gray room, damp and dimly lit. A gray-faced bartender stood statuesquely behind a deserted bar. When they entered he set two glasses on the bar and filled them from a dusty bottle. “How much?” the gaunt man asked.

“Thirty,” the bartender answered.

The gaunt man counted out the money. “I shouldn’t have asked,” he said. “It’s always thirty—no matter where I go. Thirty this, or thirty that; thirty days or thirty months or thirty thousand years.” He raised his glass and touched it to his lips.

Chris followed suit, the rawness in him screaming. The glass was so cold that it numbed his fingertips, and its contents had a strange Cimmerian cast. But the truth didn’t strike him till he tilted the glass and drained the darkness; then the quatrain came down from the attic of his mind where he had stored it years ago, and he knew suddenly who the gaunt man was.

So when at last the Angel of the Drink

Of Darkness finds you by the

river-brink,

And, proffering his Cup, invites

your Soul

Forth to your Lips to quaff it—do not

shrink.

But by then the icy waves were washing through him, and soon the darkness was complete.

* * *

Dead!

The word was a hoarse and hideous echo caroming down the twisted corridor of his mind. He heard it again and again and again—

dead . . . dead . . . dead

—till finally he realized that the source of it was himself and that his eyes were tightly closed. Opening them, he saw a vast starlit plain and a distant shining mountain. He closed them again, more tightly than before.

“Open your eyes,” the gaunt man said. “We’ve a long way to go.”

Reluctantly, Chris obeyed. The gaunt man was standing a few feet away, staring hungrily at the shining mountain. “Where are we?” Chris asked. “In God’s name, where are we?!”

The gaunt man ignored the question. “Follow me,” he said and set off toward the mountain.

Numbly, Chris followed. He sensed coldness all around him but he could not feel it, nor could he see his breath. A shudder racked him. Of course he couldn’t see his breath—he had no breath to see. Any more than the gaunt man did.

The plain shimmered, became a playground, then a lake, then a foxhole, finally a summer street. Wonderingly he identified each place. The playground was the one where he had played as a boy. The lake was the one he had fished in as a young man. The foxhole was the one he had bled and nearly died in. The summer street was the one he had driven down on his way to his first postwar job. He returned to each place—played, fished, swam, bled, drove. In each case it was like living each moment all over again.

Was it possible, in death, to control time and relive the past?

He would try. The past was definitely preferable to the present. But to which moment did he wish to return? Why, to the most precious one of all, of course—to the one in which he had met Laura.

Laura

, he thought, fighting his way back through the hours, the months, the years. “Laura!” he cried out in the cold and starlit reaches of the night.

And the plain became a sun-filled street.

* * *

He and Minelli had come off guard duty that noon and had gone into the Falls on a twelve-hour pass. It was a golden October day early in the war, and they had just completed their basic training. Recently each of them had made corporal, and they wore their chevrons in their eyes as well as on their sleeves.

The two girls were sitting at a booth in a crowded bar, sipping ginger ale. Minelli had made the advances, concentrating on the tall dark-haired one. Chris had lingered in the background. He sort of liked the dark-haired girl, but the round-faced blonde who was with her simply wasn’t his cup of tea, and he kept wishing Minelli would give up and come back to the bar and finish his beer so they could leave.

Minelli did nothing of the sort. He went right on talking to the tall girl, and presently he managed to edge his stocky body into the seat beside her. There was nothing for it then, and when Minelli beckoned to him Chris went over and joined them. The round-faced girl’s name was Patricia and the tall one’s name was Laura.

They went for a walk, the four of them. They watched the American Falls for a while and afterward they visited Goat Island. Laura was several inches taller than Minelli, and her thinness made her seem even taller. They made a rather incongruous couple. Minelli didn’t seem to mind, but Laura seemed ill at ease and kept glancing over her shoulder at Chris.

Finally, she and Pat had insisted that it was time for them to go home—they were staying at a modest boarding house just off the main drag, taking in the Falls over the weekend—and Chris had thought,

Good, now at last we’ll be rid of them.

Guard duty always wore him out—he had never been able to adapt himself to the two-hours-on, two-hours-off routine—and he was tired. But Minelli went right on talking after they reached the boarding house, and presently the two girls agreed to go out to supper. Minelli and Chris waited on the porch while they went in and freshened up. When they came out Laura stepped quickly over to Chris’s side and took his arm.

He was startled for a moment, but he recovered swiftly, and soon he and Laura were walking hand in hand down the street. Minelli and Pat fell in behind them. “It’s all right, isn’t it?” Laura whispered in his ear. “I’d much rather go with you.”

“Sure,” he said, “it’s fine.”

And it was, too. He wasn’t tired anymore and there was a pleasant warmth washing through him. Glancing sideways at her profile, he saw that her face wasn’t quite as thin as he had at first thought, and that her nose was tilted just enough to give her features a piquant cast.

Supper over, the four of them revisited the American Falls. Twilight deepened into darkness and the stars came out. Chris and Laura found a secluded bench and sat in the darkness, shoulders touching, listening to the steady thunder of the cataract. The air was chill, and permeated with ice-cold particles of spray. He put his arm around her, wondering if she was as cold as he was; apparently she was, for she snuggled up close to him. He turned and kissed her then, softly, gently, on the lips; it wasn’t much of a kiss, but he knew somehow that he would never forget it. He kissed her once more when they said good night on the boarding house porch. She gave him her address.

“Yes,” he whispered, “I’ll write.”

“And I’ll write too,” she whispered back in the cool damp darkness of the night. “I’ll write you every day.”

* * *

Every day

, said the plain.

Every day

, pulsed the stars.

I’ll write you every day.

And she had, too, he remembered, plodding grimly in the gaunt man’s wake. His letters from her were legion, and so were her letters from him. They had gotten married a week before he went overseas, and she had waited through the unreal years for him to come back, and all the while they had written, written, written—

Dearest Chris

and

Dearest Laura

, and words, words, words. Getting off the bus in the little town where she lived, he had cried when he had seen her standing in the station doorway, and she had cried too; and the years of want and of waiting had woven themselves into a golden moment—and now the moment was shreds.

Shreds

, said the plain.

Shreds

, pulsed the stars.

The golden moment is shreds. . . .

The past is a street lined with hours

, he thought,

and I am walking down the street and I can open the door of any hour I choose and go inside. It is a dead man’s privilege, or perhaps a dead man’s curse—for what good are hours now?

The next door he opened led into Ernie’s place, and he went inside and drank a beer he had ordered fourteen years ago.

“How’s Laura?” Ernie asked.

“Fine,” he said.

“And Little Chris?”

“Oh, he’s fine too. He’ll be a whole year old next month.”

He opened another door and went over to where Laura was standing before the kitchen stove and kissed her on the back of the neck. “Watch out!” she cried in mock distress. “You almost made me spill the gravy.”

He opened another door—Ernie’s place again. He closed it quickly. He opened another—and found himself in a bar full of squealing people. Streamers drifted down around him, streamers and multicolored balloons. He burst a balloon with his cigarette and waved his glass. “Happy New Year!” he shouted. “Happy New Year!” Laura was sitting at a corner table, a distressed look on her face. He went over and seized her arm and pulled her to her feet. “It’s all right, don’t you see?” he said. “It’s New Year’s Eve. If a man can’t let himself go on New Year’s Eve, when

can

he let himself go?”

“But, darling, you said—”

“I said I’d quit—and I will, too—starting tomorrow.” He weaved around in a fantastic little circle that somehow brought him back to her side. “Happy New Year, baby—Happy New Year!”

“Happy New Year, darling,” she said, and kissed him on the cheek. He saw then that she was crying.

He ran from the room and out into the Cimmerian night.

Happy New Year

, the plain said.

Happy New Year

, pulsed the stars.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind . . .

The gaunt man still strode relentlessly ahead, and now the shining mountain occulted half the sky. Desperately, Chris threw open another door.

He was sitting in an office. Across the desk from him sat a gray-haired man in a white coat. “Look at it this way,” the gray-haired man was saying. “You’ve just recovered from a long bout with a disease to which you are extremely susceptible, and because you are extremely susceptible to it, you must sedulously avoid any and all contact with the virus that causes it. You have a low alcoholic threshold, Chris, and consequently you are even more at the mercy of that ‘first drink’ than the average periodic drinker. Moreover, your alternate personality—your ‘alcoholic alter ego’—is virtually the diametric opposite of your real self, and hence all the more incompatible with reality. It has already behaved in ways your real self would not dream of behaving, and at this point it is capable of behavior patterns so contrary to your normal behavior patterns that it could disrupt your whole life. Therefore, I beg you, Chris, not to unleash it. And now, goodbye and good luck. I am happy that our institution could be of such great help to you.”

He knew the hour that lay behind the next door, and it was an hour which he did not care to relive. But the door opened of its own accord, and despite himself he stepped across the dark threshold of the years. . . .

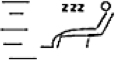

He and Laura were carrying Friday-night groceries from the car into the house. It was summer, and stars glistened gently in the velvet-soft sky. He was tired, as was to be expected at the end of the week, but he was taut, too—unbearably taut from three months of teetotalism. And Friday nights were the worst of all; he had always spent his Friday nights at Ernie’s, and while part of his mind remembered how poignantly he had regretted them the next day, the rest of his mind insisted on dwelling on the euphoria they had briefly brought him—even though it knew as well as the other part did that the euphoria had been little more than a profound and gross feeling of animal relaxation.

The bag of potatoes he was carrying burst open, and potatoes bounced and rolled all over the patio. “Damn!” be said, and knelt down and began picking them up. One of them slipped from his fingers and rolled perversely off the patio and down the walk, and he followed it angrily, peevishly determined that it should not get away. It glanced off one of the wheels of Little Chris’s tricycle and rolled under the back porch. When he reached in after it his fingers touched a cold curved smoothness, and with a start he remembered the bottle of whiskey he had hidden the previous spring after coming home from a Saturday-night drunk—hidden and forgotten about till now.