Metallica: This Monster Lives (11 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

Phil sat back down, wondering how he was going to handle this one….

It’s important for me to point out that Phil welcomed us into his world as enthusiastically as any subject we’ve ever documented. Although Lars had specifically invited us out to San Francisco to film the sessions, I had assumed that this therapist, whoever he was, would need some convincing before letting us in the door. We had prepared ourselves for an initial rejection, figuring we would have to jump through several hoops before he allowed something so unusual as someone filming his patients’ therapy sessions. But Phil was immediately receptive to us. He had filmed some of his sessions in the past (although not for public consumption), and he firmly believed that cameras could have beneficial effects, either as a “truth serum” that kept people honest with themselves and one another, or simply as a motivator, since some people feel a compunction to talk if they know a camera is on them. Phil’s hospitality with us may have given him a sense of quid pro quo:

we’re all in this together.

By getting too close to Metallica, he eventually complicated his relationship with them. And there were times when he encouraged a closeness in us that complicated our relationship with him. By submitting to therapy, I was partly to blame.

Of course, any of the eventual awkwardness between Phil and us might still have happened if I hadn’t unburdened myself on his couch. But it was an early example of how roles could get tricky with this film. Was Phil a coauthor of

Some Kind of Monster

? For that matter, was he a de facto member of Metallica? Were the cameras enabling the therapy or vice versa? The filmmakers, the band, and Phil: who was authoring whom? As the filmmaking process went on, these questions became increasingly thorny. The moment I said yes to Phil may have marked the first growing pains of the three-headed monster.

CHAPTER 6

NO REMORSE

Day One at the Presidio. The bunker setting foreshadowed the long, hard slog that would ultimately result in

St. Anger.

(Courtesy of Niclas Swanlund)

01/21/01

INT. FROM 627, RITZ-CARLTON HOTEL, SAN FRANCISCO - DAY

JAMES:

I just think [making this record] is going to be fun.

KIRK:

Yeah.

JAMES:

I mean, that’s the part I’m looking forward to: no bad vibes. Just go in loose and completely relaxed, with a smile, and just kick major ass. I mean, just having no luggage, no weights on you, no nothing-just free, really free, and just going for it.

KIRK:

Like a vacation.

JAMES:

Completely.

KIRK:

Should be like a goddamn vacation.

PHIL:

One thing I wanted to ask you guys: What do you think about becoming-how should I say it?-more in tune to one another, more like a family, more sensitive, more-dare I say it

loving toward each other? Is that going to take the edge off?

LARS:

Exactly. I was going to touch upon that.

PHIL:

Is anybody afraid of that?

LARS:

I was actually going to say, I think it’s going to go in the opposite direction. I can’t really hear much of the record yet, but I just-you know, the words “brutal” and “ugly” and “come to mind. We’ve had some fun with a lot of blues-based stuff and backbeats and that kind of stuff, and I just hear ugliness, real ugliness, and really just fucked-up shit. Ugly sounds and nasty energies and just weird kind of … RRRRRRRGGGGH!

JAMES:

Like I said, fun.

In the fifty-year history of rock and roll, has any band besides Metallica endured such intense and prolonged group therapy? Probably not. Has any other band lasted this long without trying, at least once, to make music collaboratively? I doubt it. As weird as it was for these rock and rollers to have daily therapy sessions, it was weirder that they’d lasted twenty years without having a spontaneous jam session.

In a way, this unwillingness to jam is what landed Metallica on Phil’s couch. Any Metallica fan knows that the band has always had a rigid hierarchy and an entrenched creative process: James and Lars solicited ideas (mostly riffs) from the others; James and Lars together wrote, arranged, and assembled basic tracks of the songs, which they presented to the others; Kirk added his solos and Jason added bass lines. Kirk had always accepted the status quo, but Jason, whose “second-class citizen” status in Metallica ran much deeper than Kirk’s, bristled at it.

1

To deal with these feelings, he began his Echobrain project with a couple of young musicians he’d met in his neighborhood. As Echobrain

evolved into a real band, Jason defied Metallica’s rule (really James’s) that no band member spend significant time with another band. James didn’t want to bend the rule, but neither did he want to change the way Metallica made music by giving Jason more input. Jason’s departure underscored that this impasse was untenable if Metallica were to remain a healthy unit.

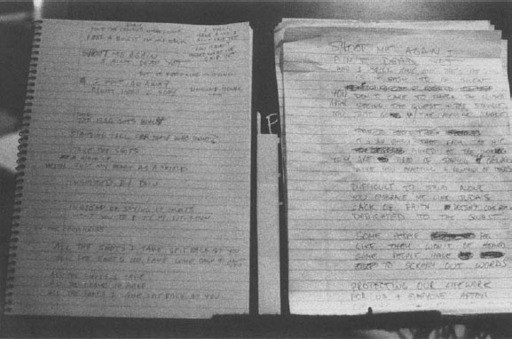

For the first time in Metallica’s history, song lyrics were created democratically. (Courtesy of Bob Richman)

I wouldn’t be surprised if James and Lars found the idea of jamming—and, more broadly, of opening themselves up to input from others—to be more frightening than therapy. You could always just clam up and recede into yourself in therapy, letting others do the talking. To take the same tact while writing music meant losing control of the music. Even within the tight James-Lars nexus, the two Metallica leaders had long ago reached an implicit understanding that neither was allowed to criticize the other’s contributions. This created an almost constant state of tension, as Bob Rock discovered when he came aboard to produce Metallica’s 1991 self-titled breakthrough. “It was horrible,” he recalls. “It was always just James and Lars, and I was between them. I never knew what to do. They were always on opposite ends, with Kirk trying to keep the peace. Jason was the outsider, and they would just

squash

him.”

Except for the part about Jason, who was gone by the time we arrived on the scene, that scenario should be familiar to anyone who has seen

Monster.

As our film makes clear, old habits were very difficult to break. After more than a decade on the front lines, Bob was glad they were at least trying. “It was definitely a welcome change. Before, I always felt like I was being thrown together with these monsters. It was almost like going to war.” He laughs. “They’re like great soldiers. They’re monsters and horrible people, but they have another side that’s very lovable.” Realizing they needed to shed their old personas, they had no choice but to become, in Bob’s words, “four guys fooling around in a garage.”

It certainly seemed to me that the love was flowing during those early Presidio sessions. You could really feel it from Kirk. As he says in the film, he was thrilled that James was opening up the lyric-writing process.

2

Metallica really did seem like a young band, a little shy with each other but thrilled by their collective buzz. Their childlike enthusiasm was genuinely touching.

So why did I have the sneaking suspicion that what I was hearing was, to use one of Metallica’s favorite derisive terms, pretty “stock”?

I mean, the music sounded

okay

, but it seemed to occupy some bland middle ground. It didn’t sound like the old Metallica or a compelling version of a new Metallica. I questioned my judgment, however, because the guys were so excited. Besides, what did I know? By the time we finished making

Monster

, I would feel like a Metallica expert, but at this point my knowledge of the music was mostly limited to what we used in the

Paradise Lost

films. I’d gone through a brief Black Sabbath phase in my youth, although I was always more into the Stones and the Dead. More recently, my tastes had run more to the Cure and the Clash. Mine may not have been an expert opinion, but I did have some idea of what Metallica were capable of, owing to the songs we had used in

Paradise Lost

and my work with the band on VH1’s

FanClub.

It never occurred to me that what I was hearing at the Presidio would one day evolve into an album as great as

St. Anger

, but my main impetus in making a Metallica movie had never been the music. I was more interested in the disconnect between their onstage image and who they were as people. I was fascinated by their business savvy and also by the complex dynamic between James and Lars. I wanted to make a film that would tackle stereotypes in much the same way as

Brother’s Keeper

and

Paradise Lost

had done.

I was, however, concerned about the quality of the music inasmuch as it pertained to the job we were hired to do. Remember, we were being paid to put together an infomercial about the making of an album. We hoped somehow to

elevate the project by delving into Metallica’s personal lives, but that was really a secondary consideration. I was glad to be working again and didn’t want to screw this up. If this album wasn’t headed for greatness—and it didn’t really sound to me like it was—making a decent promo film would be that much harder.

To the extent that I did dream of this film becoming more personal and less promotional, I was less bothered by the music than I was by the lack of focus and often superficial nature of much of the therapy. Although I had been immediately struck by the parallels between what these guys were going through and the situation with Bruce and me, after several sessions I began to feel that they were barely scratching the surface. I had recently spent a few sessions with a therapist in New York, to help me deal with the helplessness and despair caused by the

Blair Witch 2

fallout, so it was incredible—not to mention inspirational—to see guys like this even attempt group therapy Still, I couldn’t help noticing that they were circling around important issues, veering off into a million tangents, and issuing “breakthroughs” like “I’m really getting to know you.” To make the film we really wanted to make, we’d have to find a way to make the therapy work cinematically. As a filmmaker who mentally edits during shooting, I was starting to realize the challenge of presenting meandering, discursive conversations with no real resolution in such a way that would be interesting to watch while remaining true to their essence.

I was particularly concerned about James in this regard. He just wasn’t saying much in the sessions. It wouldn’t do to have a Metallica film where the band’s leader stays silent. James didn’t look bored—he looked positively uncomfortable. It began to dawn on me that the therapy, though at times apparently superficial, was dredging something up in James. I couldn’t say just what. But if you go back to the earliest therapy scene in

Monster

—the one where Lars wonders aloud if our cameras will destroy the intimacy of therapy, to which James responds, “What intimacy? What the fuck are you talking about?”—you get a sense of what James was going through. He’s smiling, but it’s a smile that says he’d rather be anywhere but there. Even outside room 627, you could tell that James was uncomfortable. When the band sits around patting each other on the back about the great music they’re making, James is silent. “You don’t seem too psyched,” Lars says.

All I could decipher was that something wasn’t quite right with James. Much later, when it was time to begin editing

Monster

, I was struck by how much James’s unease is obvious on-screen. Perhaps there is something to Phil’s belief that our cameras brought out the truth. James, though he was able

to resist this pressure, was nonetheless no better able to remain perfectly mute. He might not have been talking out loud, but our cameras were listening hard.

I don’t think I was any better at keeping my insecurities to myself. I still had no idea that we were capturing so much emotional complexity. I was afraid we weren’t capturing much of anything, and toward the end of that second week I was determined to be proactive. I decided that if the therapy and studio material wasn’t sufficiently compelling, then we needed to go deeper. One day as we began filming, I heard Lars mention a meeting he’d had with Bob the night before, to discuss their thoughts on how the new music was progressing. A few minutes later, as Lars sat behind his drums warming up, I walked up and tried to get his attention. At first he didn’t see me—or pretended not to. I waved a little to get his attention.