Metallica: This Monster Lives (12 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

“Hey, Lars, I heard you and Bob had a meeting about the new album.”

He stared straight ahead, pumping his feet on his trademark dual-kick drum setup. “Uh-huh.”

“You know, you really need to tell us about everything that goes on that we might want to film.”

“Okay” he said tentatively.

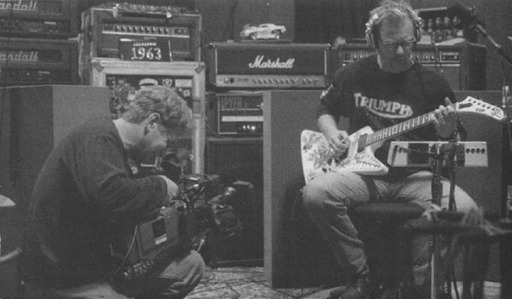

Cinematographer Bob Richman shoots James. (Courtesy of Annamaria DiSanto)

James with his daughter, Cali (Courtesy of Bob Richman)

“I mean, if we’re going to make an effective documentary about you guys making this album, we need to—”

He swiveled around to face me. “Hey!” That’s all he said. Then he swiveled back and kept pumping his feet. I took that to mean, “I’m Lars Ulrich, the drummer of fucking Metallica, the biggest band in the fucking world, and don’t tell me when to invite you to tag along with a camera.” All he needed to say was that one dismissive word: “Hey!”

The band decided to take a three-week vacation after the second week. There was a small impromptu party at the Presidio studio on the last night before the break. James cut out right after work was done, barely saying goodbye, but everyone else stuck around. Sean Penn, a close friend of Lars’s, had been hanging around the studio that day, although he made it very clear that he wasn’t interested in appearing in the film. (“I don’t want to be like Warren Beatty in

Truth or Dare.

”) Someone handed me a bottle of vodka.

I was hanging out with rock stars and a movie star, kind of buzzed at two

A.M.

when Lars walked up and presented me with one of those ethical quandaries that come with making documentaries.

“You want to go hit some bars with me and Sean?”

Did I? Well, yeah, sure I did. Maybe Lars was trying to make up for snapping at me, although it was clear that we were all off the clock, that this would

just be a social call, a chance to hang out, not something we’d film. I pondered this invitation for a second and decided its social nature was exactly what made me uneasy.

SOME KIND OF MONSTER

The first time we see Metallica at the Presidio in

Some Kind of Monster

, they improvise over a riff played by James. As the jam gets going, he ad-libs vocals by lifting some lyrics from the Metallica song “Fuel.” That happened on our first day of shooting at the Presidio; that riff was literally the first new Metallica music we documented. It’s easy to miss it in its embryonic form, but that riff eventually became the song “Some Kind of Monster.” Over the next couple weeks, “Monster” became the first real song to emerge in a rough state. Bob Rock played a special role in its creation by suggesting the lyrical theme and zeroing in on the riff that eventually became the song’s chorus.

As soon as “Some Kind of Monster” began to coalesce, I thought it would make a good title for our film (even though at that point our “film” was still officially an infomercial). The titles for our other movies have emerged very late in the filmmaking process, so I soon grew bored with this one, even as it began to catch on with Bruce and the rest of the crew. Toward the end of filming, I started leaning toward

Madly in Anger

, a line from “St. Anger.” But during the editing process, we all began to notice that

Some Kind of Monster

was a perfect title, considering what Metallica was going through, especially James’s struggle with the “beast” that was his band. So the title stuck.

The song would continue to evolve throughout the recording of

St. Anger.

As much as I like the final incarnation, I prefer the Presidio version. There’s a rawness to it that’s missing from the finished song, which I think sounds a bit too manipulated and “produced.” I think my preference is partially due to the emotional response the original song triggers in me. It takes me back to those days at the Presidio, when I was so thankful to be working again and excited to be in the presence of people who seemed like they knew the secret of creating art as a collaborative unit. Of course, I—and they—had a lot to learn.

“Monster” was a natural choice to play over our closing credit roll, though it was ultimately too monstrous for us: the song clocks in at over eight minutes, five of which were edited out so that its length matched our end credit sequence.

As I said before, I’m all for documentary filmmakers spending time with their subjects. But as with any other meaningful relationship, that trust has to be earned. After months of bonding with the Wards while making

Brother’s Keeper

, we knew we’d reached a turning point when Roscoe named some of his turkeys after us. With

Monster

, we were dealing with celebrities, an entirely different situation. I really didn’t consider Lars to be a personal friend at that point—a professional acquaintance, sure—so to hit the town would have made me feel like a fan being tossed a bone by a rock star, which is the last way I wanted Metallica to perceive me. If we were to have a relationship, it would have to be based on mutual respect. There are several people in Metallica’s inner circle who started out as fans. They’re now part of the team, but some of their old roles endure—kind of like a former assistant who, despite a promotion, is still treated like an assistant by the boss. I felt like the only way Bruce and I were going to get the access we needed was if Metallica saw us as professional filmmakers, not celebrity hangers-on.

So, while it took a lot of willpower, I told Lars, no, thanks, I had a plane to catch the next day (which was true). A part of me felt like I had blown a fun opportunity but I told myself that if a friendship was going to develop, this wasn’t the way to start. I also wanted to make it clear that I wasn’t here because I was into those sorts of perks.

I flew back to New York the next day with a lot to think about. It had been an interesting couple of weeks, but I still felt I needed to make sure that if I continued with this project, it would be for the right reasons—not just because I needed the money or wanted to work again. I conceived of this as a modest project, but it was still one that would carry my name. After

Blair Witch 2

, this was a very important consideration.

I also owed it to the band and its management to be up front about why we thought it was important to film the therapy and other personal stuff if our assignment was to do a promotional film. I wanted to be completely honest with everybody while figuring out a way to nudge the film in other directions.

There was also the issue of Bruce’s involvement. Besides the fact that collaborating with him was the ethical thing to do, since we had gotten to know Metallica together, I knew that our collaboration would make it a better film. We had gotten along really well the past few weeks. But we had never worked out

the exact parameters of our new working relationship. I was thinking a lot about the quandary James had gotten himself into with Jason, unable to relinquish control but not able to let go completely. I could relate. As it turned out, Bruce made it really easy, perhaps anticipating how much I loathe confrontation. We had an unspoken understanding that we wouldn’t sweat the details until later. Although we still hadn’t discussed our two-year separation, during which we closed down our production company all that mattered was that he was back onboard.

We drew up a provisional budget with Metallica’s managers in New York. Elektra Records, the band’s label, would provide all the funding, with 50 percent of the cost taken out of Metallica’s album royalties. We spent the break making preparations for the film, firming up our crew, working out a schedule, and generally preparing ourselves for the chaotic state our lives enter when we make a movie. The filmmaking team of Berlinger and Sinofsky was back in business. It felt really good to be working together again—kind of like getting back together with a girlfriend you regretted dumping.

We flew back to San Francisco to rejoin Metallica as the guys returned from vacation. As we checked into our hotel, it felt like we’d never missed a beat—making dinner plans, deciding what we needed for the next day’s shoot, making sure Bruce had a refrigerator in his room for his diabetes medication, getting the candy taken out of my minibar because I have no willpower. It had been two years since we’d been on a shoot together, but as Bob would say to James deep in this film’s future, it felt like the next day.

As we retired to our rooms, we actually shot each other a thumbs-up. We didn’t dare say it, but we knew we were thinking the same thing: Please, let something bad (but not

too

bad) happen to Metallica to make our film interesting.

We weren’t disappointed.

CHAPTER 7

EXIT LIGHT

05/03/01

INT. ROOM 627, RITZ-CARLTON HOTEL, SAN FRANCISCO - DAY

LARS:

As we continue to push forward into uncharted [musical] territories, what is it that we’re scared of? It would be awesome if Phil could help us with that a little bit. What is the fear of?

KIRK:

Lack of originality. We don’t want anyone to accuse us of having a lack of originality. That’s the way I see it. I think we want to stand alone on our hill and be seen as an entity that’s completely original.

LARS:

It’s a lot of fucking pressure!

PHIL:

One of the things I hear you guys say every now and then is that you want to be different, not just original, and there is a difference there.

LARS:

Different from the groups of people that we get lumped in with, or different from what we’ve done before?

PHIL:

What do you think?

LARS:

I mean … I don’t know!

PHIL:

I think that one of the things that’s happened over the last few weeks or months is that there’s a greater respect and closeness, an appreciation of one another. You’ve been letting down your defenses, and therefore you’re feeling more open to the world. There’s less of a need to be different for the sake of being different, or different because you’re trying to be against something, or different because you feel like you don’t fit in somehow. So if we’re talking about what’s healthy, it’s nice for you to choose originality, because it’s something that comes from a creative gesture, as opposed to, “We want to preserve the sanctity of being different because we don’t know how to belong.”

JAMES:

I feel like there’s nothing wrong with [wanting to be different.]

PHIL:

It’s not a matter of right and wrong…. Part of my role is helping you clarify your motives. And I do believe that if you’re driven by fear, it does affect your creativity. When you’re trying

not

to be something, or trying to protect yourself against something, it tends to siphon energy. So I think it’s good for us to check out our fears. I mean, you guys respect your uniqueness, you respect your originality, you respect what you’ve come up with, which is very special.

LARS:

I think that if you look at the history of what we’ve done for the last twenty years, our originality doesn’t exist in its own vacuum. The originality is always the result of molding together a bunch of different things, and being fortunate to have our own X factor that somehow become a part of the things we’re molding together, which results in something unique. And that unknown X factor is something we’ve never been able to define, but when we make music together, there’s an unknown thing that creeps into all the things that we take inadvertently from other people, the things that inspire us. Whether it’s been this record or the Black Album or whatever, that’s always been true. Whether it’s been Diamond Head or Mercyful Fate or AC/DC, there’s always been something that’s sparked us into going in different places, and ending up in this beautiful original state. And I just think we should just be aware that that’s always been present in our lives and in our career to some degree.