Microbrewed Adventures (23 page)

Islandic Vellosdricke

Gotland Island, Sweden

NEVER EVER EVER EVER trust a homebrewer who says, “This is the last beer we're going to taste.” NEVER EVER in a million years

EVER!

I

LEARNED MANY YEARS AGO

that homesick Swedes brought the dandelion to America. Now I could scarcely doubt this as we drove past expansive fields yellow with carpets of dandelions blazing against a startlingly blue springtime sky on the island of Gotland. Surrounded by the Baltic Sea, Gotland is a small island, about 25 miles wide and 50 miles long, situated off the southeast coast of Sweden. There, dense stands of birch and pine trees accent flowering trees and red, white, yellow and blue springtime tulips and daffodils. The sea is dark blue and cold; the winds are brisk.

Sixty-four-year-old Vello Noodapera greeted Swedish Homebrewing Society member Jesper Schmidt and me at the Gotland airport. We were both curious about the legendary beer of Gotland Island. Overwhelmed by the excitement of our arrival, Vello immediately set the record straight: “Do you know what day is today?” Was it something special? I didn't know, and with a thirsty smile I asked him to explain. “It is Folknykterhetens Dag, which roughly translates to âa day of people's soberness.'” My god, I had arrived on a national day of abstinence! I thought to myself, “Shit! Get a grip, Charlie! You might get off on smelling the dandelions.” But Vello quickly confided with a hearty laugh, “â¦but we'll ignore it.”

We were on our way to Vello's small farm and later to Sweden's first brewpub (it had officially opened only two weeks before my arrival), the Virungs

Bryggeri. My quest was to discover the mysteries of the island's special beer, Gotlandsdricke. The 45-minute drive along scenic and winding roads was interrupted briefly as we stopped at a roadside parking area. It may have been 10 in the morning, but it was not too early for a homebrew. At this time of year the sun stubbornly sets late anyway. Up popped the trunk of Vello's Saab and within seconds Jesper, Vello and I were toasting the occasion with a mugful of delicious ale, brewed with the local baker's yeast. I knew I was about to have my horizons broadened.

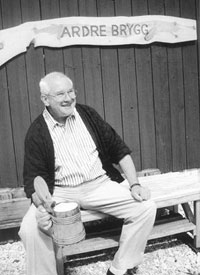

I had no idea how wonderful this day was about to become. As we approached the farm, I noticed in the distance an American flag flying high on a pole. Vello proudly explained, “That is in your honor, Charlie. It flies near my house and homebrewery today.” Off on the side-wall of a large red barn, a skillfully carved and painted signproclaimed “The Ardre Brygg”(Ardre Brewery). From the room behind that wall emerged the simple mash, lauter and brewing kettles from which Vello proudly brewed his beer. From home-fashioned tubs and adapted pieces of dairy equipment, Vello Noodapera brewed some of the best damn beer I had in all of Europe. What I was particularly interested in was the specialty of the island, Gotlandsdricke, ale brewed with smoked malt, hops, juniper branches, bread yeast and water.

Now it would be simple to assume that one could learn and brew this unique beer by following a recipe, but I discovered, as with all traditional beers, that if one wishes to come close to au

thenticity, it is absolutely imperative to experience it firsthandâand in your hand. I did. From this experience I came away with a feeling of admiration for a beer loved by the people who make it.

Vello Noodapera with his brewery kettle and Gotlandsdricke

Gotlandsdricke is brewed everywhere on this tiny island. It is estimated that 5,000 hectoliters of this beer is homebrewed here by its 50,000 residents. That's 10 liters homebrewed for every man, woman and child on the island. The island is self-sufficient, with its own barley, hops, malt houses and yeast strains.

Dan Andersson, one of Vello's brewing neighbors, soon arrived for this occasion with a most recent batch of Gotlandsdricke. I drooled with anticipation, watching amazed as this amber nectar was poured from a wooden vessel into a magnificent mug made from juniper wood. The rich, creamy head and the aromatics from the juniper resulted in love at first sip. Wow, was this stuff ever good! A huge pile of birchwood logs caught my eye and I asked whether the malt was smoked with birch with the bark left on. They confirmed my speculation: “Yes, we leave the bark on the wood when we smoke the malt.” No small detail, since birch bark itself has its own unique qualities. “But everyone makes their own style of Gotlandsdricke,” Jesper translated to me from a side conversation going on in Swedish. Details, details. How did they do it? Freshly cut juniper (note: juniper is not the same as cedar) branches are boiled in water for about two hours to make an aromatic amber broth. I noted that the juniper was of the variety that is usually low growing and difficult to handle because of the very thorny nature of the needles (I immediately recalled seeing these types of bushes growing in home gardens and on the mountains of my home state, Colorado).

This is the brewing liquor, which is added to crushed malted barley. Thirty percent is malt dried from the heat and smoke of burning birch logs. The remaining malt is the brewer's preference, consisting mostly of pale lager-type malt. Some of the amber water is reserved for sparging. The lauter vessel and bottom screen is lined with more freshly cut boughs of juniper. The mash is then poured into the lauter vessel and sparged (rinsing the grains with hot water), and sweet aromatic malt extract is drawn off the bottom. In the kettle local hops are usually used, though the more experienced homebrewers were now making the effort to import German-grown varieties.

When the mash is cool, what seemed to be an infinitesimal amount of baker's yeast is added. At Vello's brewery, about one square centimeter of cake yeast was used for a 100-liter (about 25 gallons) batch. The beer was snorting, foaming and in full fermentation within six hours. I didn't understand the significance of the careful utilization of yeast until after I visited the brewpub in the nearby village, where Gotlandsdricke also was made. Added

to 800 liters (about 200 gallons) of fresh wort was a mere 25 grams (less than one ounce) of cake yeast. This is the equivalent of using a half-ounce of dried yeast for a 200-gallon batch of beer! Infinitesimal by brewing science standards, but it worked well.

Vello Noodapera, Gotland

Someone mentioned, “We tried using cultured brewing yeasts, but the quality was not the same.” When asked why so little yeast was used, no one seemed to have a scientific explanation. Though I now postulate that because this yeast is so active, a small amount is desirable to reduce the quantity of heat generated during the initial fermentation. With greater amounts of yeast, the explosive activity would generate heat that might in turn cause the yeast to produce undesirable flavor compounds, typical of high-temperature fermentations. The relatively cool environment and viability of this yeast produced a balance of flavors the people of Gotland Island had learned to love.

At Vello and Dan's homebrewery recordkeeping was not a habit, but from my senses I surmised they brewed a beer at 1.050 (12.5 degrees B) original gravity. Color was about 14 SRM, and the hop character of Hallertauer contributed about 30 units of bitterness. Their Gotlandsdricke had a fruity and pleasant juniper taste and a smooth, distinctive smoky flavor. But friendly rivalries existed among Gotland's homebrewers, and everyone had his own secret recipe and styles: sweet, bitter, strong, weak, dark, pale, sour, with more or less smoke and juniper. We finished Vello and Dan's beer and continued our daylong expedition to Virungs Bryggeri, the island's brewery/brewpub in the small village of Romakloster. In fact, the small cottage and barn compound seemed to be the entire village. There we visited Lillis Svärd and his family, who raise sheep, run a smokehouse and meat house and operate a small malt house, brewery and attached inn. Lillis malts his own barley and was experimenting with growing and malting wheat and spelt.

A lightly smoked (relatively speaking) version of Gotlandsdricke was brewed using 40 percent lightly smoked malt along with some Munich malt bought from a commercial malt house. Lillis's other beer is called Drog öl, brewed with pale and Munich malt and honey. Lillis had been a homebrewer for the past ten years and had recently gone commercial. Though he was working on a system with which to bottle his beers, you would have had to be

there to experience the finest essence of his craft. Lillis has since closed his brewery in pursuit of developing concrete tepees, but I can't imagine he has stopped homebrewing.

VELLO'S GOTLANDSDRICKE

The fruity and refreshing character of juniper boughs and berries combined with the mellow warmth of gently smoked malt emerge as a magical combination. It is not without reason this centuries-old beer tradition remains regionally popular. If you have access to fresh juniper, you can recreate this Scandinavian experience at home. The recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

I believe that as you brew your next batch of beer, whatever your style might be, Lillis and Vello will be tending their most recent batch of Gotlandsdricke. I fell in love with the stuff and was very pleased with how my first homebrewed batch turned out. I did have a little help, since Lillis gave me about 10 pounds of birch-smoked malt he had made, but you can produce your own style of “dricke” using ingredients locally available. Why? Because you're a homebrewer and microbrewer.

And if you can drink it out of a wooden juniper mug, please do. It's simply wonderful.

Flights of the ImaginationâEccentric, Creative and Wild The Netherlands and Belgium

“Geezus I'm blasted. No, not wasted. Blasted. Do I get combat pay for this trip? Everyone seems to want to feed me three times more than I could possibly eat and then pour me five times more than I can possibly drink. I am truly saturated. HELP! I mean having a beer at 10 a.m. is one thing but continuing until 1 or 2

A.M

. one after another and knowing that the next day begins at 7

A.M

. is an awesome thing to consider.”

âF

ROM MY TRAVEL JOURNAL

, M

AY

1995,

THE YEAR

I

VISITED THE

N

ETHERLANDS AND

B

ELGIUM

.

Long Days' Journeys into Nights

P

ERHAPS

there is no country in the world more under-discovered and under-recognized for its beer culture than the Netherlands. Amsterdam is both a magnificently beautiful and wild city. Explore its streets and alleys with beer in mind and you will discover brewpubs, world-class beer bars/cafés and memorable beers. Go beyond the city limits to the countryside towns and villages and you will begin to realize the beer passion homebrewers and microbrewers have embraced as their own. There is much more to Holland than

Heineken. My introduction began in the small town of Vllesingen, the Netherlands, with beer, homebrew, microbrew, cider, liqueur, distilling, herbal, horticulture and wine master Jan Van Schaik.

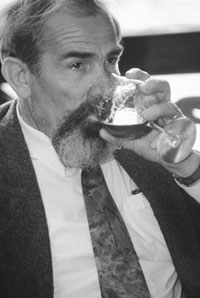

Jan has a small goatee and trim mustache, reminding me of photographs I've seen of Louis Pasteur. I learn that Jan frequently gives lectures about Pasteur, one of his favorite scientists and heroes. He has written numerous books on homebrewing, wine, cider and distilling. He not only is an expert at all things alcohol, but has helped lobby the Dutch legislature to legalize home distilling and established the Dutch beer judge program. Born in 1936, Jan continues to love the finer aspects of alcohol, but seems to overflow with a passion for beer more than anything else.

He lives with his wife, Irma, in the small coastal village of Vllesingen, on the most southwesterly tip of the Netherlands. His garage is an experience, magnificent to behold, filled with herbs, spices, brewing ingredients and an unfathomable collection of homemade beer, wine, brandy and liqueur.

Within hours of my arrival from Colorado, Jan whisked me away to a truly micro microbrewery, the Scheldebrouwerj in the village of 'S Gravenpolder/Bergen op Zoon. These guys impressed as the epitome of true homebrewers. Their hand-built microbrewery, with tiled floors and walls, is in immaculate order. They were brewing 10 hectoliters (about 265 gallons) a weekâonly on the weekends. The owner, Kaees Loenhout, was a social worker involved with the child protection board by week, brewing on the weekends with his assistant, Louis Spoelstra. Louis's day job was as an oil refinery cracker, electrician and mechanic; he had a keen interest in engines, steam engineering and electronic gad-geteering. The brewery has grown a little since my visit in

1995, but they continue to brew with skill and passion as only original homebrewers can do. Their beers were unlike anything I had ever had.

Jan Van Schaik, the Netherlands

The first thought that went through my mind was that American microbreweries have a lot to discover when it comes to beer character. They made a beer called De Zeezuiper Natuurbier, a 7.5 percent top-fermented bottle-conditioned ale with 5 to 10 percent corn or maize, malt, coriander, curação peel and woodruff, all deliciously blanketed with an unbelievable creamy, dense head. They referred to their yeast as Belgian “zampus.” Their hopping rates were low at 20 bittering units, but the beers wonderfully impacted my palate as though they had 30 units of hop bitterness. De Zeezuiper is fermented for 10 days, then cold “lagered” or aged for three weeks before bottling. The bottles are conditioned at warmer temperatures for 10 days before being released from their tiny microbrewery. Whew! What a beer!

They also brewed a Winterbier with 8.5 percent alcohol, made with pilsener, amber, crystal and caramel malts. With the skillful addition and balance of cinnamon, coriander, Belgian candi sugar, Czech Saaz and German Hersbrucker hops, this ale becomes indescribably awesome and unlike anything I've ever had by any American homebrewer or microbrewer.

The repertoire of beers went on. They have made a 6.5 percent (low-alcohol beer!) called Lamme Goedzak, as well as a Liberation 1945â1995 Teugs Teugje Meibok Beer. How did they develop all this brewing knowledge? As homebrewers first, but not without some professional training. Kaees went to the University of Ghent for three years of Sundays to study brewing. Every Sunday morning he would commute to Ghent to

attend classes. What he has learned he imparts to others as a beer judge and beer judge teacher.

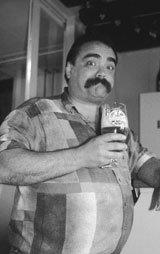

Brewer and founder Kaees Loenhout of the Scheldebrouwerj

Â

MUG

IS THE DUTCH WORD

for mosquito. It is also the name of one of the most charming pub-restaurants in the Netherlands and Jan's favorite local specialty beer bar. A tiny place and easy to miss, De Mug is wonderfully nestled in the village of Middelburg only a 10-minute drive from Vllesingen. De Mug's regularly published newsletter features news of the beers they offer and events they sponsor. One can't help notice the abundance of candles and large casks of old medium sherry, dry Madeira and rich ruby port behind the “brown” bar, so called because of its ambience. Bottles of Tabasco sauce are tucked away amidst the carved wooden nooks and crannies and an American Express sticker can be seen on the window, but that's as far as 1995 seemed to express itself, except for the selection of 64 classic Dutch and Belgium beers (though they did have Murphy's and Guinness stout and Paulaner Salvator doppelbock as well). Heineken is offered, but it isn't the Heineken light lager the rest of the world knows; rather rare bottles of Heineken “Oud Bruin” and Amstel “Meibok” were offered as world classics.

The pub was established in 1973. Barend Midavaine, the owner, really loves what he is doingâand it shows. At De Mug I met folks who make beer, sell beer, think beer and drink beer. Barend's wife is a homebrewer. Need I say more about the heart and authenticity of this tiny bar near the Zeeland coast?

I enjoyed a few beers, including a Trappist-brewed Westvleteren and a Rochefort. I savored their complexity and freshness, thinking that this was the finale for the day's visits, but I was wrong.

Nearby in the small village of Hilvarenbeek, we approached an old brick building. I was taken behind its unassuming garage door. I glanced to the side and noted that the iron gate had a hop motif designed into one its supporting posts. Inside this unassuming brick building is a brewery that has been turned into a working museum. The two-hectoliter (53 gallons) Stichting Museumbrouwerij De Roos brewhouse, built in 1850, was hidden from the Germans during World War II and thus saved from being scrapped for war materials. The original Stichting De Roos Brewery was a top-fermenting ale brewery, one of but a few breweries that did not change its beer to the more popular lager style. Harrie de Leijer De Roos, son of the founding grandfather, only recently renovated the brewery premises. At the time of our visit he had the support of the local city council for plans on offering to the local homebrew club an opportunity to brew at this historic brewery museum.

Upon returning to Jan and Irma's home we took off our street shoes and slipped into wooden Dutch shoes to roam around the soggy yard and into the crammed floor-to-ceiling garage. We began tasting Jan's various liqueurs, including a homemade Scottish Drambuie indistinguishable from the real thing and a mystery liqueur whose origins Jan asked me to guess. I tasted vanilla, cocoa, coffee and Curação. But Jan flabbergasted me when he confided that he had hand roasted his own cocoa beans, saying, “You really can't get the really true taste of cocoa unless you roast your own beans. They were very difficult to find, but I did.”

We had dinner, and the beer, brandy and stories continued. I learned that Holland's only Trappist monastery (De Schaapskoot) would be hosting the next year's Dutch National Homebrew Championship and would brew a special beer in honor of homebrewing. Meanwhile I prepared for another day's adventures with a short night's sleep.

Â

DE VAETE BROUWERIJ

in Lewedorpwas was a microbrewery I visited, conceived by yet two more homebrewers. Located at the end of a long dirt road running alongside a canal in an extremely small farmer's shed. Inspired by their 10 years of homebrewing, Ton de Bruin and Alexander Roovers had become weekend microbrewers, producing about 25 gallons at a time. Keeping 30 different strains of yeast on culture, they fermented their Plder Blondje, Tripel, Winterbier, pale ale, Dubbel and Pa's Best in five-gallon carboys. By trade, Ton is a laboratory technician and Alexander a microbiology technician. Their annual production at the time of my visit was about 660 gallons a year. All for the love of beer.

Homebrewing activity in the Netherlands is a relatively small part of the beer landscape, but the few dozen homebrew clubs throughout the country have a great impact on beer education and awareness. Each of the clubs inspires homebrewers with beers and the passion of camaraderie. It is clearly evident that their gatherings are about both beer and family. The next evening we joined about 40 people in a small village community center. I talked about homebrewing and beer judging in America. We then all turned our focus on Meibocks (May/Maibocks), a light-colored German-style strong, malty bock beer that the Dutch have embraced as their own. Tasting six commercial Dutch Meibocks and then 12 homebrewed Meibocks, we judged and chose a winner.

Â

IN AMSTERDAM

we met 40 beer judges. This was a Dutch Beer Judges Guild special field trip to visit a brewpub, drink beer, go on a walking tour of

Amsterdam brewery sites, drink beer, attend a seminar and, of course, drink beer. These guys are thrifty when it comes to non-alcoholic endeavors. I was tagging along. We stayed at a $10-a-night youth hostel in the center of one of the diciest areas of Amsterdam. There must have been several hundred travelers bunking in the dormitory-style accommodation. I was in Room 7 with at least 60 guys. Despite all the wonderful beer we had indulged in, I had difficulty sleeping. What does a pod of 30 hippos belching and farting on the riverbanks of the Zambezi sound like? This was an experience to be forgotten, but nonethess it was being experienced at least once in my life. Good beer helped. The sound of 50 men snoring started kind of low key with about 10 or 12 snorting randomly. By 2

A.M

. there were at least 30 or 40 all snoring their way to wherever their dreams were taking them. But the most interesting thing was that by about 3

A.M

. they had all cycled into snoring in unison. I was not hallucinatingâthe effects of alcohol had worn off by that time. I had difficulty believing what I was hearing: 59 Dutchmen snoring in harmony, lending a spooky ambience to the darkness of the room, lit by one lonely and beckoning exit sign.

I don't know how much any of you know about Amsterdam, but, well, shall we say, it can get pretty damned weird. Strange-looking people, the smell of legalized hashish and marijuana wafting its way out of numerous street cafés. And hookers, their whorehouses lining the alleys and side streets. It was in this atmosphere that we started our two-hour morning brewery tour. While the guide was explaining the sights in Dutch, all these beer guys were focused on was the one building we were told used to be a brewery 100 years ago. It looked like a brick building to me. Meanwhile in my sleep-deprived state, I did not believe what I was seeing in the picture windows on either side of the historic brewery site. As our guide was pointing out architectural features, I was looking across the canal and up the street. It was only about 9

A.M

., but there were “ladies” shaking their booties, winking and carrying on in all manners. Farther down the street were dozens of the most bizarre sex shops I'd ever seen. Meanwhile, our guide was rambling on about the brewer in 1789 and the beer and the pubs. Junkies (though friendly ones at that) were staggering around amongst us and the thousands and thousands of other well-to-do tourists, young and old, shopping for chocolates, teacups, T-shirts, postcards and the weirdest-looking dildos I've never even imagined!