Microbrewed Adventures (25 page)

Kettle and Crucifix, Westmalle Trappist Brewery

We ate lunch across the street at the Trappiste Café. From there, where did we go? Oh, of course, to visit another brewery. North, not too far from Westmalle and almost to the Netherlands to visit the Sterkens Brewery in Hoogstraten. Built in 1880, it is only about a 15,000-hectoliter (about 13,000 barrels) per year operation, a truly original microbrewery. Stan Sterken offered me beer after the tour. I accepted and immensely enjoyed their Poorter. Not to be confused with American-or British-style porter, this beer is velvety smooth, offering dark ale qualities not commonly brewed by other breweries large or small. Sterken's Poorter has a “round” nutty malt character without any of the caramel or crystal malt flavor you'd normally anticipate in an amber or brown ale. Furthermore, despite its coppery color there is virtually no roast malt astringency. There is a slight touch of banana character in the flavor, but not pronounced or anywhere near the level of many of the dark abbey-style ales of Belgium. Alcohol character was not evident in flavor, aroma or mouthfeel.

SWITCH AND TOGGLES PREPOSTEROUS POORTER

This is a prized recipe that achieves the smooth, “round” nutty malt character and complexity of Belgian malts, with a slight touch of banana character in the flavor. The recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

The word

sublime

comes to mind. Honestly, I drank this beer scratching my head and truly wondered how it possibly could have been made. My 25 years of brewing experience didn't help solve the mystery. What impressed me the most was the notion that as a brewer I still could find the excitement of learning about and brewing something new.

After a brief consultation with the importer, I was given direction: “It's the malt.” I learned on my adventures in Belgium how special Belgian malts can be. I also learned to discern the character of Goldings hops and the important role they play in many Belgian specialties.

World-Class Belgian Breweries

Belle Vue, Palm, Moortgat and Lindeman

I

N OLDEN TIMES

spontaneously fermenting lambic breweries proliferated throughout the area of Brussels. Now only a few remain, and even fewer offer the traditional unsweetened styles so revered by beer enthusiasts, who appreciate and savor the tart, acidic, fruity characters of this true “champagne” of beers.

The Belle Vue Brewery is the largest of the Belgian lambic breweries and is now owned by the Belgian brewery giant Interbev. This was already the case when I visited in 1995. Their lambics are often criticized for being sweetened beyond traditional recognition, and some will not even consider them true lambics.

It is true that the final product is so sweet that it bears very little resemblance to a true lambic. Its base is a true brewed lambic blended with juice and sweeteners to suit what they perceive as consumer preference. But a tour of the brewery reveals secrets that very few care to explore because of its mega-brewery and sugared reputation.

Inside there are over 11,000 large wooden oak barrels fermenting and ag

ing the real thing! I learned that Belle Vue's lambics are aged for years in these barrels. The small bungholes in the barrel remain open for years, during which fermentation foams out and over the barrel.

For the making of Kriek (Belgian cherry) lambic, ripe, whole cherries are harvested in July and added to six-month-fermented lambic. Fermentation resumes with the addition of natural sugar from the cherries and continues for an additional two to two and a half years. It is easy to tell which barrels have fermenting Kriek inside. There are a handful of birchwood twigs stuffed in and partially emerging from each oak barrel. Why? So that the pits don't emerge and clog the hole during the second fermentation, thus avoiding the danger of building pressure and exploding barrels. Eighty kilograms (about 175 pounds) of cherries are added to each 520-liter (about 550 gallons) oak barrel. That is a lot of cherries, and most of the production staff is busy stuffing cherries into bungholes during the two short weeks when the fruit is received at the brewery.

During the maturation process a moldlike skin from wild yeast forms a layer on the surface of the beer, inhibiting oxidation and evaporation. The entire process is natural, from the spontaneous fermentation begun by airborne yeast and bacteria. Spiders abound in the brewery. These are the sacred creatures of every lambic brewery; their webs capture bacteria-laden flies.

After a tour of the main cellars housing the oak barrels, we were led to a smaller cellar tucked away in a quiet corner of the brewery. There, I couldn't believe my eyes. Hundreds of champagne-type bottles were resting on their side, aging and refermenting lambic. What a comforting sight! I was treated to a bottle. This select aged lambic was exquisite and a real treat, but is rarely available. Most fascinating was an explanation of how to translate the sediment inside the bottle. Brewer Jacque De Keersmaecker explained how to “read” the sediment as he lifted a bottle lying on its side, carefully so as not to disturb the sediment. As the light silhouetted the sediment we could see that it had spread itself into a pattern, clinging to the side of the bottle. Jacque explained that there are two types of sediment along the side of the bottle. The dark, dense and somewhat oval-patterned sediment is bacterial; the featherlike sediment that extends up and down from the bacterial center is

Brettanomyces

yeast. The yeast sediment is actually formed in very thin, featherlike strands. You can tell how acidic the beer will be by how large the bacterial sediment is, and how influenced by

Brettanomyces

yeast the lambic will be by the extending patterns of featherlike fronds of sediment.

You can go to the brewery for a tour any time. In 1995 you could also bring your own container and fill it up directly from their unblended barrelsâa little-known treat.

T

HE

500,000-

HECTOLITER PALM BREWERY

is a small brewery by some standards, but to taste their beers is to taste the soul of Belgian beer passion. On a tour, the owner took a few of us to the side and showed us the dried whole hops used in one of their special dry-hopped beers. We were told that there is a crew of people who individually tear apart each hop cone by hand before adding it to the aging tanks. I had my doubts until he confided to us how wonderful American homebrewers are: “I have to thank the homebrew club in Los Angeles. I believe they are called the Maltose Falcons. They advised me to use Styrian hops when dry hopping. I learned quite a bit from my visit there.”

On the second brewery tour of the day, the brewery Moortgat (brewer of Duvel and other beers) was explained. Interestingly, this tour was indicative of many of the other brewery tours I and several other brewers experienced while in Belgium. There were few, if any, secrets kept from us. The breweries even handed out flow charts explaining every detail of ingredients, processes and equipment for each of their brews. American brewers, small or otherwise, rarely go into as much detail as the Belgians. I supposed they really didn't feel they had anything to hide. It would be virtually impossible to duplicate their beer with another system and even if you could, you would still be missing the 100-plus years of beer tradition and experience.

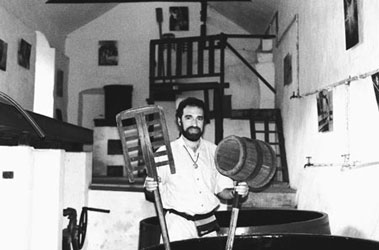

Roger Musche tapping gueuze lambic at Lindeman Brewery

In the evening I was part of a private tour of the Lindeman Brewery, brewers of spontaneously fermented lambic beers

that are widely exported to America. My first impression: What a funked-out, totally bizarre brewery! Words cannot describe the funkiness of this farmhouse brewery just outside of Brussels. Roger Musche, whom I had met in Zimbabwe while enjoying my sorghum beer indulgence, was the head brewer. He greeted us with the compassion of a brewery father and excitedly led us through the inner depths of the brewery. The fermenting rooms smelled like an old urinal and had the ambience of an ancient water closet. As we sampled various batches of lambic from tanks and barrels, Roger tossed leftover beer onto the walls and floor to add to and feed the existing micro flora of bacteria and wild yeasts, so important to the brewery's success.

Tours uncompromisingly lead to the tasting room. We sat comfortably at wooden tables, the walls decorated with labels and posters outlining the history of the brewery. We tried their

kriek

(cherry),

peche

(peach),

framboise

(raspberry) and sweetened faro lambics. But it was unanimous among the invited that the best beers were the refermented gueuze lambic, no longer sold, and their cassis lambic, which was a failure in the marketplace. The most interesting “beer” was called “Tea Beer,” actually a blend of sour fermented lambic and green tea.

When you have the opportunity to reciprocate beer for beer, it is a common courtesy to do so. Rarely have I had the opportunity to share my beers with brewers in other parts of the world. But having anticipated this tour for nearly a year, I had brought along my own homebrewed “lambic-style” cherry and raspberry lambics. Unfortunately, they did not hold up to the two weeks of traveling I had just undergone. Through agitation and less-than-ideal conditions they had lost their edge, crispness and complexity. I was not offended

by their less-than-accepting reception. But my 10-year-old Gnarly Roots Lambic-style barley wine was greeted with enthusiasm. I noted with interest that usually this 10 percent alcohol barley wine tasted very strong, but on this occasion, and after tasting 8 and 9 percent Belgian-style ales with regularity for the past two weeks, it did not. I suppose that proves the theory of relativity, doesn't it?

BELGIAN-STYLE CHERRY-BLACK CURRANT (KRIEK-CASSIS) LAMBIC

This is one of the most phenomenal lambic-style beers I've tastedâand I made it! I used a combination of sour cherries and chokecherries, but you have the option to use currants if you wish. This beer is a two-year process, but well worth the effort. You'll need a quiet corner to age the slowly fermenting and evolving beer. Avoid extreme temperatures. Use the best-quality fully ripened fruit you can buy or pick yourself. Cherries and currants should have a balance between sweet and sour. Fresh or fresh-frozen are best. Here is the recipe for my finest lambic. It can be found in About the Recipes.

Cerveza Real in Latin America

A

LAND OF THIRST

,

Latin America has some of the lightest-tasting beers on the planet. The beer landscape from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego can be quite monotonous unless you tune in to creative fermentations.

Greatly influenced by German brewers who had immigrated to Latin America, there was at one time a diversity of ales and lagers available regionally in cities and the countryside. However, nationalization of brands and beer monopolies have greatly diminished the choices available to the beer drinker. Even if you wanted to pay more money for a full-flavored beer, it is difficult to find one. Fortunately, there are signs that all this may be changing. Brewpubs and microbreweries are emerging in Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Colombia, Peru and several other nations. There are homebrewing co-ops and clubs celebrating their discovery of beer flavor and diversity. Even some of the large brewing companies are beginning to offer amber ales, bocks and wheat beers.

Slowly and patiently, the dormant Latin American passion for beer flavor is reemerging. The hot climate does not mean the beer needs to be tasteless. Pioneers are beginning to succeed by providing choice. People are discovering and drinking their beer with a great deal of appreciation. A microbrewed adventurer will find them.

J

OSÃ WATCHES HIS CUSTOMERS

enjoying beer at his taverna in Tijuana, Mexico. Most are guys, local residents, some with their wives or girlfriends. José notes that one guy is enjoying a chilled half-liter of a pilsener-style lager while his female companion seems disinterested, bored and sipping on a glass of water. José walks over to the table and presents a glass of pilsener to the woman, explaining that he is only giving her the beer so she can feel part of the scene. She doesn't need to pay for it nor even drink it. She thanks him, admitting that she really doesn't like beer. “But this beer is different,” he insists, then goes on to briefly explain the merits of all-malt beer with flavor and character. He leaves. Five minutes later he observes from afar that there is one inch of beer missing from the complimentary glass. Ten minutes more go by and the glass is half full. Twenty-five minutes later he returns to the table with another glass of beer, offering the same dealâ“you only need to keep the beer company and no need to pay.”

The woman becomes a convert and wonders why a beer could be so dif

ferent from the typical Mexican light lagers she is accustomed to disliking. The year is 2004, and José has begun his own small revolution.

José Gonzales, Tijuana Beer

José Antonio González comes from a beer family. All his life he has been surrounded by beer. His father moved from state to state, distributing and selling beer for the large Mexican breweries. José dreamed of one day having his own brewery and developing the Mexican beer drinker's appreciation for microbrewed beer.

The beginning of his microbrew adventure took him to Germany and the Czech Republic, where he discovered the pleasure and drinkability of Czech pilseners. Experiencing the house-brewed dark lager at the Prague Brewery U Flecku, José asserts, “I would drink all day this wonderful beer. My face would feel warm. I would sleep well at night and wake up the next morning with my head feeling wonderfulâand by 12 o'clock noon I wanted to drink more beer. I never had these kinds of experiences with the beer I knew in Mexico.”

On a visit to Prague, José asked a brewmaster how much corn, rice and sugar was formulated into these beers. The brewmaster explained, “Rice is for making sake. Corn is for making whiskey. Sugar is for making rum. Malt is for making beer.” José's world was turning on edge. He had been touched by the passion for good beer. He did not know it at the time, but he was in the company of family brewers from Pilsner Urquell and Královský pivovar KruÅ¡ovice (Brewery KruÅ¡ovice).

Soon thereafter a Czech brewhouse, a Czech brewmaster and Czech malt, hops and yeast were on a voyage to Mexico's northwestern coastal city of 3 million, Tijuana. In the year 2000, Cerveza Tijuana was brewing, bottling and distributing all-malt Czech-inspired pilsener (Güera) and dark lager (Morena) along with other specialties available only on the brewery site at its Czech-styled pubtaverna. If you visit and José is there, you will recognize him by the twinkle in his eye and his excitement about Czech-style lager.

José and his son Ozbaldo have become impassioned and recognize that one of their major challenges is the education of the Mexican beer drinker about beer variety and things

like foam, drinking out of a glass, hops, malt, flavor and the fact that lime is not needed for his beer. These are the same challenges microbrewers have faced throughout the world as they return the flavor, culture and tradition to beer.

CZECH-MEX TIJUANA URQUELL

Czech-style pilseners are something special. They are the original pilseners. They are traditionally unique with their soft, almost honeylike malt aromatics and flavor. Czech hops are flavorful and deliciously herbal, with a thirst-quenching character. This is a modern-day formulation of traditional Czech pilseners with a touch of Mexican lightness that deserves your attention. The recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

In the land of Modelo, Corona and Tecate, there are now a few more lagers from which to choose.

E

TERNALLY SPRING

,

at an elevation of nearly 10,000 feet, surrounded by volcanoes towering over 20,000 feet and only 50 miles from the hot, humid tangle of the world's largest jungle, stands America's oldest existing brewery. As though its surroundings were not spectacular enough, the brewery's history inspires the mind while contemplating the origins, wisdom and tenacity of its founders over 470 years ago.

The high Andean air in the city of Quito, Ecuador, is bright, clean and easily calmed by the country's readily available pilsener and Club Premium lager beers. Ecuador, a country situated on the equator and the size of Colorado, has a lot to offer: the towering mountains of the Andes; tropical beaches; the Amazon basin jungle; brilliant deserts; Indian, African and Spanish culture; and America's oldest brewery.

As part of the Spanish conquest, the city of Quito was founded in 1534. It was only a matter of days before work on a church and monastery was initiated. Seven monks who had traveled to the South American continent from Flanders (now part of Belgium) brought their yearning for beer as it had been

brewed in the old country. Wheat was imported and cultivated, and soon America's first brewery was malting, brewing and fermenting America's first wheat beer.

In the garden of the monastery one of the padres gave me a short history of the brewery, which has now been restored as a museum. Through an interpreter, he explained that cultivation of wheat was followed in later years with the introduction of barley. The small, simple brewery was popular with the growing population at the monastery and expanded into a more “serious” brewery in 1595.

Up until 1957, the five-to-six-barrel (U.S. size) brewhouse malted its own barley and sun dried it. The brewery continued operation until 1967, when according to the padre, the Pope issued an order halting brewing operations. The tradition of the Franciscan Order of Monks embraced a vow of poverty and humility, and the new Vatican's interpretation did not perceive beer brewing as part of those values.

However, up until the brewery ceased operation the monks were brewing 12 batches of beer per week, half of which the monastery church kept for itself and the other half of which was distributed to other churches and monasteries in the area. Wheat beers and pale beers as well as very dark beers were regularly brewed, according to the padre's story.

These beers are now only a memory in the minds of a select few people residing in Quito. The manager at the small hostel where I stayed in told me that his father used to work in the brewery. He couldn't recall very much except a locally produced proteinous substance that was used in the brewing process. I figured it must have been some sort of clarifying agent similar to isinglass, which is derived from the swim bladders of certain fish. It is often used in traditional English ale brewing.

The brewery was preserved as a museum with the help of two Ecuadorian breweries, Cervezas Nacionales of Guayaquil and Cerveceria Andina of Quito. Adjacent to and part of the museum is a preserved beautifully small, beer hall. The flavor of it all seems to linger as a cross between Flemish and Germanic brewing traditions. A visit to the monastery brewery is well worth the effort if you ever find yourself in the city of Quito. And I know the padre appreciated the bottle of my own homebrew that I gave him after our tour of the brewery at the monastery of San Francisco.

The following is partially excerpted from an article by Paul V. Grano about the brewery and the brewing of one type of beer by the monastery. The article appeared in the January 1966 issue of

The Brewers Digest

.

Established in 1534 the brewery at the San Francisco Monastery, Quito, Ecuador

The brewhouse consists of a copper-lined concrete mash kettle, a wooden lauter tub with a bronze false bottom and a hot water tank made of an old German hop cylinder. All heating is by direct wood fire. Thirty-three pounds of pilsener malt plus 50 pounds of caramel malt and 20 pounds of black malt (milled in a coffee grinder in the monastery) are mashed in and the usual infusion method is followed. Since the agitator, which was installed for the Fathers, is inadequate they have to take turns in stirring the mash in order to avoid burning on the bottom. This is quite a hot and heavy job.

The mash then runs to the lauter tub by gravity, and the wort is pumped back to the mash kettle by hand. Here 100 pounds of brown sugar dissolved in hot water is added. The hop rate for the batch is two pounds. When the boiling of the wort is finished the wort once again runs by gravity to the surface cooler and is left there over night. The next morning, the yeast that we [La Victoria Malting/Brewing Company] provide them is added and fermentation goes on at about 60 degrees F (15.5 C). The original extract is about 10.5 degrees balling and when the beer has fermented down to one degree balling above the end fermentation the beer is bottled immediately. The bottles are filled through four siphons and crowned by hand. The empty bottles as well as the crown corks were [recently] given to the monastery by our brewery when

this type of bottle was discontinued for commercial purposes some years ago.

The fermentable extract still in the beer produces about .5 percent CO

2

by weight or 2.7 percent by volume after 10 to 12 days of storage when the beer is ready for consumption. The alcohol is about 3.4 percent by weight and the taste is very pleasant. The Fathers are served one glass for lunch and one for supper. About one hour before serving, the crown corks are lifted slightly; otherwise the beer would pour like champagne.

To conclude, I would mention a small episode, which took place a few weeks after we had first agreed to assist the Fathers. I went over to the monastery to ask the “Brewmaster” how the beer had turned out, to which he answered me with a smile that where he had previously used one padlock to close his storeroom, he now had to use two!