Miracles of Life (20 page)

Authors: J. G. Ballard

Family life has always been very important to me, far more

important, I suspect, than to people of my parents’ generation.

I often wonder why many of them bothered to have

children at all, and assume that it must have been for social

reasons, some ancient need to enlarge the tribe and defend

the homestead, just as some people keep a dog without ever

showing it affection, but feel secure when it barks at the

postman.

Perhaps I belong to the first generation for whom the

health and happiness of their families is a significant indicator

of their own mental well-being. The family and all the

emotions within it are a way of testing one’s better qualities,

a trampoline on which one can leap ever higher, holding

one’s wife and children by their hands.

I enjoyed being married, the first real security I had ever

known, and easily coped with the strains and early struggles

of a writer’s life. I enjoyed being a father who was closely involved with his children, pushing them in their pram

through the streets of Richmond and Shepperton, and later

driving with them across Europe to Greece and Spain.

Children change so rapidly, learning to grasp the world and

learning to be happy, learning to understand themselves and

shape their own minds. I was fascinated by my children and

still am, and feel much the same way about my four grandchildren.

I have always been very proud of my children, and

every moment I spend with them makes the whole of

existence seem warm and meaningful.

In 1963 Mary was in good health, but needed her appendix

removed. She recovered slowly from the operation at

Ashford Hospital, and perhaps her resistance was affected, or

some infection lingered. She was keen to go on holiday, and

the following summer we drove to a rented flat at San Juan,

near Alicante. For a month all went well, and we enjoyed

ourselves in the bars and beach restaurants. It was the kind

of holiday where the high point is the day Daddy fell off the

pedalo. But Mary suddenly became ill with an infection, and

this rapidly turned into severe pneumonia. Despite the local

doctor, a male nurse (the practicante) who was with her constantly,

and a consultant from Alicante, she died three days

later. Towards the end, when she could barely breathe, she

held my hand and asked: ‘Am I dying?’ I’m not sure if she

could hear me, but I shouted that I loved her until the end.

In the final seconds, when her eyes were fixed, the doctor

massaged her chest, forcing the blood into her brain. Her eyes swivelled and stared at me, as if seeing me for the first

time.

We buried her in the small Protestant cemetery in

Alicante, a walled stone yard with a few graves of British

holidaymakers killed in yachting accidents. A Protestant

priest came to see me the previous day, a decent and kindly

Spaniard who did not seem upset when I declined to pray

with him. I can still hear the sound of the iron-wheeled cart

carrying the coffin across the stony ground. The priest conducted

a short service, watched by myself and the children,

and a few English residents from our apartment building.

Then the priest rolled up his sleeves, took a spade and began

to shovel the soil onto the coffin.

In late September, when San Juan beach was deserted and

the cold air was beginning to come down from the mountains,

we left the now-empty apartment building and set off

on the long drive back to England.

From the start I was determined to keep my family together.

Mary’s sisters and mother, who were an enormous help over

the coming years, offered to share bringing them up. But I

felt that I owed it to Mary to look after her children, and I

probably needed them more than they needed me.

I did my best to be both mother and father to them,

though it was extremely rare in the 1960s to find single

fathers caring for their children. Many people (who should

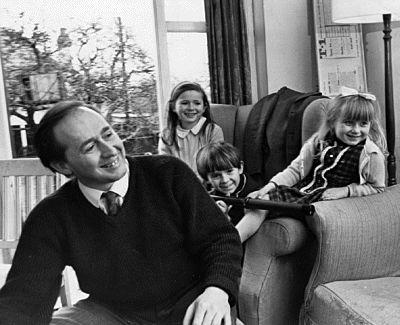

Fay, Jim and Beatrice at home with me in 1965

.

have known better) openly told me that a mother’s loss was

irreplaceable and the children would be affected for ever, as

maintained by the child psychiatrist John Bowlby. But I

seriously doubt this claim, which seems unlikely given the

hazards of childbirth – the evolutionary disadvantages if the

claim were true would have been selected against and a less

dangerous parental bond would have taken its place. I

believe that the chief threat posed by a mother’s death is,

rather, an uncaring or absentee father. As long as the

surviving parent is loving and remains close to the children,

they will thrive.

I loved my children deeply, as they knew, and we were

lucky that I had a job as a writer that allowed me to be with

them all the time. I made them breakfast and drove them to

school, then wrote until it was time to collect them. Since

day-time babysitters were difficult to come by, we did everything

together – shopping, seeing friends, visiting museums,

going on holiday, doing homework, watching television. In

1965 we drove to Greece for nearly two months, a wonderful

holiday when we were always together. I remember a

hold-up on a mountain road in the Peloponnese when an

American woman looked into our car and said: ‘You mean

you’re alone with these three?’ and I replied: ‘With these

three you’re never alone.’ Thankfully, I had long forgotten

what it was like to be alone.

I hope the children realised early on that they could

always rely on me. My son Jim, who was the oldest, grieved

deeply for his mother, but we helped each other through,

and eventually he regained his confidence and became

a cheerful teenager with a charming and witty sense of

humour. My daughters Fay and Bea soon took command of

the situation, and became strong-willed young women

before they were in their teens, deciding on our diet, which

holiday hotels we should stay at, what clothes they should

buy. In many ways my three children brought me up.

Alcohol was a close friend and confidant in the early days;

I usually had a strong Scotch and soda when I had driven the

children to school and sat down to write soon after nine. In those days I finished drinking at about the time today that I

start. A friendly microclimate unfurled itself from the bottle

of Johnnie Walker and encouraged my imagination to

emerge from its burrow and test the air. Kingsley Amis made

a point of inviting me out to lunch, and in the evening I

would often visit Keats Grove, where he and Elizabeth Jane

Howard had rented a flat. Jane was unfailingly kind, though

my presence was probably a nuisance. She cooked supper,

which we ate on our knees, while Kingsley kept a beady eye

on a television quiz show, answering all the questions before

they were out of the compère’s mouth. I am grateful to

Kingsley, and glad that I saw his generous and kindly side

before he became a professional curmudgeon.

Other friends were a great help, especially Michael

Moorcock and his wife Hilary. But, as every bereaved person

learns, one soon reaches the point where friends can do little

more than keep one’s glass filled. I missed Mary in a thousand

and one domestic ways – the traces she had left of

herself in the kitchen, bedroom and bathroom together

formed the outlines of a huge void. Her absence was a space

in our lives that I could almost embrace. Long months of

celibacy followed, during which I resented the sight of happily

married couples strolling down Shepperton High Street.

I once saw a couple laughing together in the car ahead of

me and sounded my horn in anger. After celibacy came a

kind of desperate promiscuity, a form of shock treatment in

which I was trying to will myself to come alive. I remember embracing my first lover – the estranged wife of a friend –

like a survivor at sea clinging to a rescuer. I’m grateful to

those friends of Mary’s who rallied round and knew that it

was time to bring me back into the light. In their way they

were thinking of Mary rather than me, wise and kindly

women who were concerned that Mary’s children should be

happy.

A year or so after Mary’s death I saw her in a dream. She

was walking past our house, skirt floating on the air, smiling

cheerfully to herself. She saw me watching her from the

doorstep of our house and walked on, smiling at me over her

shoulder. When I woke I tried to keep these moments alive

in my mind, but I knew that in her way she was saying goodbye,

and that at last I was beginning to recover.

I am sure that I changed greatly during these years. On the

one hand I was glad to be so close to my children. As long as

they were happy nothing else mattered, and success or

failure as a writer was a minor concern. At the same time I

felt that nature had committed a dreadful crime against

Mary and her children. Why? There was no answer to the

question, which obsessed me for decades to come.

But perhaps there was an answer, using a kind of extreme

logic. My direction as a writer changed after Mary’s death,

and many readers thought that I became far darker. But I like

to think I was much more radical, in a desperate attempt to

prove that black was white, that two and two made five in the

moral arithmetic of the 1960s. I was trying to construct an

imaginative logic that made sense of Mary’s death and

would prove that the assassination of President Kennedy and

the countless deaths of the Second World War had been

worthwhile or even meaningful in some as yet undiscovered

way. Then, perhaps, the ghosts inside my head, the old

beggar under his quilt of snow, the strangled Chinese at the

railway station, Kennedy and my young wife, could be laid to

rest.

All this can be seen in the pieces I began to write in the

mid 1960s, which later became

The Atrocity Exhibition

.

Kennedy’s assassination presided over everything, an event

that was sensationalised by the new medium of television. The endless photographs of the Dealey Plaza shooting, the

Zapruder film of the president dying in his wife’s arms in his

open-topped limousine, created a kind of gruesome

overload where real sympathy began to leak away and only

sensation was left, as Andy Warhol quickly realised. For me

the Kennedy assassination was the catalyst that ignited the

1960s. Perhaps his death, like the sacrifice of a tribal king,

would re-energise us all and bring life again to the barren

meadows?

The 1960s were a far more revolutionary time than

younger people now realise, and most assume that English

life has always been much as it is today, except for mobile

phones, emails and computers. But a social revolution took

place, as significant in many ways as that of the post-war

Labour government. Pop music and the space age, drugs and

Vietnam, fashion and consumerism merged together into an

exhilarating and volatile mix.

Emotion, and emotional sympathy, drained out of

everything, and the fake had its own special authenticity. I

was in many ways an onlooker, bringing up my children in a

quiet suburb, taking them to children’s parties and chatting

to the mothers outside the school gates. But I also went to

a great many parties, and smoked a little pot, though I

remained a whisky and soda man. In many ways the 1960s

were a fulfilment of all that I hoped would happen in

England. Waves of change were overtaking each other, and at

times it seemed that change would become a new kind of boredom, disguising the truth that everything beneath the

gaudy surface remained the same.

In 1965 I met Dr Martin Bax, a north London paediatrician

who published a quarterly poetry magazine called

Ambit

. We became firm friends, and years later I learned that

his wife, Judy, was the daughter of the Lunghua headmaster,

the Reverend George Osborne. She and her mother had

returned to England in the 1930s and spent the war years

there. I began to write my more experimental stories for

Ambit

, partly in an attempt to gain publicity for the magazine.

Randolph Churchill, son of Winston and a friend of

the Kennedys, objected publicly to my story ‘Plan for the

Assassination of Jacqueline Kennedy’. Churchill made a

song and dance in the newspapers, demanding that

Ambit’s

modest Arts Council grant be withdrawn and describing my

piece as an irresponsible slander, all this at a time when the

ordeal of Mrs Kennedy and her courtship by Aristotle

Onassis were ruthlessly exploited by the tabloid newspapers,

the real target of my satire.

A prime engine of change in the 1960s was the entirely

casual use of drugs, a generational culture in its own right.

Many of the drugs, led by cannabis and amphetamines, were

recreational, but others, heroin chief among them, were

intended for use in the intensive care unit and the terminal

cancer ward, and were highly dangerous. Moral outrage had

a field day, while preposterous claims were made for the

transformation of the imagination that could be brought about by LSD. The parents’ generation fought from behind a

barricade of gin and tonics, while the young proclaimed

alcohol to be the real enemy of promise.