Miracles of Life (23 page)

Authors: J. G. Ballard

Life with Claire has always been interesting – we have

often driven together across half of Europe and never once

stopped talking. We share a huge number of interests, in

painting and architecture, wine, foreign travel, politics (she

is keenly left-wing and impatient with my middle-of-theroadism),

the cinema and, most important of all, good food.

For many years we have eaten out twice a week, and Claire is

an expert judge of restaurants, frequently finding a superb

new place long before the critics discover it. She is a great

reader of newspapers and magazines, has completely

mastered the internet and is always supplying me with news stories that she knows will appeal to me. She is a great cook,

and over the years has educated my palate. She has very

gamely put up with my lack of interest in music and the

theatre. Above all, she has been a staunch supporter of my

writing, and the best friend that I have had.

When I first met Claire I was dazzled by her great beauty,

naturally blonde hair and elegant profile. Sadly, she has suffered

more than her share of ill health. Soon after we met,

she underwent a major kidney operation at a London hospital,

and I remember walking with her down the Charing

Cross Road on the day she was discharged, on the way to

Foyle’s to buy the ‘book’ of her operation, a medical text of

the exact surgical procedure. It is typical of Claire that she

took the trouble to write a letter of thanks to the surgeon

who invented the procedure, then retired to New Zealand,

and received a long and interesting reply from him. Ten years

ago she faced the challenge of breast cancer, but fought back

bravely, an ordeal that lasted many years. That she triumphed

is a tribute to her courage.

Together we have travelled all over Europe and America,

to film festivals and premieres, where she has looked after me

and kept up my spirits. At the time we met, Claire was

working as the publicity manager for a publisher of art

books, and she went onto be publicity manager of Gollancz,

Michael Joseph and Allen Lane. Her knowledge of publishing,

and many of the devious and likeable personalities

involved, has been invaluable.

Looking back, I realise that there is scarcely a city,

museum or beach in Europe that I don’t associate with

Claire. We have spent thousands of the happiest hours with

our children (she has a daughter Jennifer) on beaches and

under poolside umbrellas, in hotels and restaurants, walking

around cathedrals from Chartres to Rome and Seville. Claire

is a speed-reader of guidebooks, and always finds some

interesting side chapel, or points out the special symbolism

of this or that saint in a Van Eyck. She had a Catholic

upbringing, and lived in a flat not far from Westminster

Cathedral, whose nave was virtually her childhood playground.

Whenever we find ourselves in Victoria she casually

points out a stone lion or Peabody building where she and

her friends played hide-and-seek.

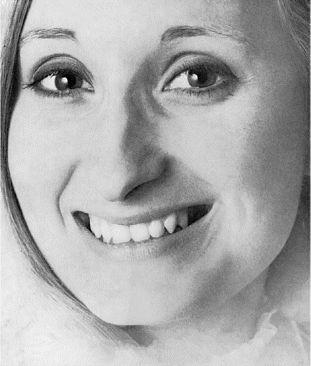

I was so impressed by Claire’s beauty that I made her the

centrepiece of two of my ‘advertisements’, which were published

in

Ambit, Ark

and elsewhere in the late 1960s. I was

advertising abstract notions largely taken from

The Atrocity

Exhibition

, such as ‘Does the Angle Between Two Walls Have

a Happy Ending?’ – a curious question that for some reason

preoccupied me at the time. In each of the full-page ads the

text was superimposed on a glossy, high-quality photograph,

and the intention was to take paid advertisement pages in

Vogue

and

Harper’s

Bazaar

. I reasoned that most novels

could dispense with almost all their text and reduce themselves

to a single evocative slogan. I outlined my proposal in

an application to the Arts Council, but they rather solemnly

Claire Walsh in 1968

.

refused to award me a grant, on the surprising grounds that

my application was frivolous. This disappointed me, as I was

completely serious, and the Arts Council awarded tens of

thousands of pounds to fund activities that, unconsciously

or not, were clearly jokes –

Ambit

itself could fall into that

category, along with the

London Magazine

, the

New Review

and countless poetry magazines and little presses.

The funds disbursed by the Arts Council over the decades

have created a dependent client class of poets, novelists and weekend publishers whose chief mission in life is to get their

grants renewed, as anyone attending a poetry magazine’s

parties will quickly learn from the nearby conversations.

Why the taxes of people on modest incomes (the source of

most taxes today) should pay for the agreeable hobby of a

north London children’s doctor, or a self-important Soho

idler like the late editor of the

New Review

, is something I

have never understood. I assume that the patronage of the

arts by the state serves a political role by performing a castration

ceremony, neutering any revolutionary impulse and

reducing the ‘arts community’ to a docile herd. They are

allowed to bleat, but are too enfeebled to ever paw the

ground.

Still, what the Arts Council saw as a prank at least put

Claire’s beautiful face into the

Evening Standard

.

And, last but not least, she introduced me to the magic of

cats.

If

The Atrocity

Ehibition

was a firework display in a charnel

house,

Crash

was a thousand-bomber raid on reality, though

English critics at the time thought that I had lost my bearings

and made myself into the most vulnerable target.

The

Atrocity Exhibition

was published in 1970, and was my

attempt to make sense of the sixties, a decade when so much

seemed to change for the better. Hope, youth and freedom

were more than slogans; for the first time since 1939 people

were no longer fearful of the future. The print-dominated

past had given way to an electronic present, a realm where

instantaneity ruled.

At the same time, darker currents were flowing a little too

close to the surface. The viciousness of the Vietnam War,

lingering public guilt over the Kennedy assassination, the

casualties of the hard drug scene, the determined effort by

the entertainment culture to infantilise us – all these had

begun to get between us and the new dawn. Youth began to

seem rather old hat and, anyway, what could we do with all that hope and freedom? Instantaneity allowed too many

things to happen at once. Sexual fantasies fused with science,

politics and celebrity while truth and reason were shouldered

towards the door. We watched the

Mondo

Cane

‘documentaries’

where it was impossible to tell the fake newsreel

footage of atrocities and executions from the real.

And we rather liked it that way. Our willing complicity in

this blurring of truth and reality in the

Mondo

Cane

films

alone made them possible, and was taken up by the entire

media landscape, by politicians and churchmen. Celebrity

was all that counted. If denying God made a bishop famous,

what choice was there? We liked mood music, promises that

were never kept, slogans that were meaningless. Our darkest

fantasies were pushing at a half-open bathroom door as

Marilyn Monroe lay drugged among the fading bubbles.

All this I tried to grapple with in

The Atrocity Exhibition

.

What if the everyday environment was itself a huge mental

breakdown: how could we know if we were sane or psychotic?

Were there any rituals we could perform, deranged

sacraments assembled from a kit of desperate fears and phobias,

that would conjure up a more meaningful world?

Writing

The Atrocity Exhibition

, I adopted an approach as

fragmented as the world it described. Most readers found it

difficult to grasp, expecting a conventional A+B+C narrative,

and were put off by the isolated paragraphs and the

rather obsessive sexual fantasies about the prominent figures

of the day. But the book has remained in print in Britain, Europe and the USA, and has been reissued many times.

In New York it was published by Doubleday, but the

editor, an enthusiastic supporter, made the mistake of

adding an advance copy to the trolley filled with new titles

that was sent up to the president’s office. There Nelson

Doubleday broke the cardinal rule of all American publishers:

never read one of your own books. He leafed idly

through

The Atrocity Exhibition

and his eye lit upon a piece

entitled ‘Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan’. The then

governor of California was a close friend, and within minutes

the order had gone out to pulp the entire edition. The

book was later published by Grove Press, home to William

Burroughs and other prominent avant-garde writers, and

since the 1990s by the very lively and adventurous Re/Search

firm in San Francisco, one of the most remarkable publishing

houses I have come across, specialists in urban

anthropology of the most bizarre kind.

In the last few years

The Atrocity Exhibition

seems to be

emerging from the dark, and I wonder if the widespread use

of the internet has made my experimental novel a great deal

more accessible. The short paragraphs and discontinuities

of the morning’s emails, the overlapping texts and the need

to switch one’s focus between unrelated topics, together

create a fragmentary world very like the text of

The Atrocity

Exhibition

.

* * *

By the time that

The Atrocity Exhibition

was published in

1970 I was already looking ahead to what would be my first

‘conventional’ novel for five years. I thought hard about the

cluster of ideas that later made up

Crash

, many of them

explored in

The Atrocity Exhibition

, where to some extent

they were disguised within the fragmentary narrative.

Crash

would be a head-on charge into the arena, an open attack on

all the conventional assumptions about our dislike of violence

in general and sexual violence in particular. Human

beings, I was sure, had far darker imaginations than we liked

to believe. We were ruled by reason and self-interest, but

only when it suited us to be rational, and much of the time

we chose to be entertained by films, novels and comic strips

that deployed horrific levels of cruelty and violence.

In

Crash

I would openly propose a strong connection

between sexuality and the car crash, a fusion largely driven

by the cult of celebrity. It seemed obvious that the deaths of

famous people in car crashes resonated far more deeply than

their deaths in plane crashes or hotel fires, as one could see

from Kennedy’s death in his Dallas motorcade (a special

kind of car crash), to the grim and ghastly death of Princess

Diana in the Paris underpass.

Crash

would clearly be a challenge, and I was still not

completely convinced by my deviant thesis. Then in 1970

someone at the New Arts Laboratory in London contacted

me and asked if there was anything I would like to do there.

The large building, a disused pharmaceutical warehouse, contained a theatre, a cinema and an art gallery (there were

also a number of flues, intended to draw off any dangerous

chemical fumes and useful, so I was told, for venting away

any cannabis smoke in the event of a police raid.

It occurred to me that I could test my hypothesis about

the unconscious links between sex and the car crash by

putting on an exhibition of crashed cars. The Arts Lab were

keen to help, and offered me the gallery for a month. I drove

around various wrecked-car sites in north London, and paid

for three cars, including a crashed Pontiac, to be delivered to

the gallery.

The cars went on show without any supporting graphic

material, as if they were large pieces of sculpture. A TV

enthusiast at the Arts Lab offered to set up a camera and

closed-circuit monitors on which the guests could watch

themselves as they strolled around the crashed cars. I agreed,

and suggested that we hire a young woman to interview the

guests about their reactions. Contacted by telephone, she

agreed to appear naked, but when she walked into the gallery

and saw the crashed cars she told me that she would only

perform topless, a significant response in its own right, I felt

at the time.

I ordered a fair quantity of alcohol, and treated the first

night like any gallery opening, having invited a cross section

of writers and journalists. I have never seen the guests at an

art gallery get drunk so quickly. There was a huge tension in

the air, as if everyone felt threatened by some inner alarm that had started to ring. No one would have noticed the cars

if they had been parked in the street outside, but under the

unvarying gallery lights these damaged vehicles seemed to

provoke and disturb. Wine was splashed over the cars, windows

were broken, and the topless girl was almost raped in

the back seat of the Pontiac (or so she claimed: she later

wrote a damning review headed ‘Ballard Crashes’ in the

underground paper

Friendz

). A woman journalist from

New

Society

began to interview me among the mayhem, but

became so overwrought with indignation, of which the

journal had an unlimited supply, that she had to be restrained

from attacking me.