Modern China. A Very Short Introduction (3 page)

Read Modern China. A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

years ago, a group of independent states that were in confl ict with one another existed in the heartland of what we now call ‘China’; literature and history from this period is recognizably Chinese, readable by those today who take the trouble to learn the classical form of the language. From 221 BCE, successive emperors and dynasties united these states, leading to a succession of dynasties that created China’s classical civilization: the Han, the Tang, the Song, the Yuan, the Ming, and the Qing among them. They created a civilization in which art, literature, statecraft, medicine, and technology all thrived.

However, the term ‘China’, or the term

Zhongguo

(‘middle kingdom’, the current Chinese word for ‘China’), was not how the people of those eras would have thought of themselves. The idea of being ‘Chinese’ in the sense that we understand it, as either 6

national or ethnic identity, is a product of the 19th century (as is the term

Zhongguo

). Yet there clearly was a shared sense of what we might call ‘Chineseness’ between these people, which outlasted the rise and fall of dynasties. What made up that identity? Most people identifi ed themselves with the ruling dynasty itself, as

‘people of the Ming’ or ‘people of the Qing’. But what lay behind this naming? How did one qualify as a ‘person of the Ming’?

Over the centuries, there has been a variety of shared attributes that have brought together the communities we know as

‘the Chinese’. From early on, Chinese society was settled and agricultural, in contrast with the nomad societies such as the Manchus, Mongols, and Jurchen with which it periodically came into contact. Features of that society, such as irrigation, have also been prominent throughout Chinese history. The size of the Chinese population has always dwarfed its neighbours, and

What is modern C

that population has increased with territorial growth over the centuries as well. In very early China, the landmass was occupied by a variety of peoples, but from 221 BCE, after the unifi cation by the Qin dynasty, dominance remained with a people whom we

hina?

recognize as Chinese (often called ‘Han’ Chinese after the next dynasty).

But why did the

Chinese

think of themselves as Chinese? Broadly, shared identity came from shared rituals. For more than 2,000

years, a set of social and political assumptions, which found their origins in the ideas of Confucius, a thinker of the 6th century BCE, shaped Chinese statecraft and everyday behaviour. By adopting these norms, people of any grouping could become ‘people of the dynasty’ – that is, Chinese.

Confucianism is sometimes termed a religion, but it is really more of an ethical system, or system of norms. In its all-pervasiveness

and

its fl exibility and adaptability to circumstances, it is somewhat analogous to the role of Judaeo-Christian norms in Western societies, where even those who dispute or reject those norms still fi nd themselves shaped by them, consciously or not.

7

Confucianism is based on ideas of mutual obligation, maintenance of hierarchies, a belief in self-development, education, and improvement, and above all, an ordered society. It abhors violence and tends to look down on profi t-making, though it is not wholly opposed to it. The ultimate ideal was to become suffi ciently wise to attain the status of ‘sage’ (

sheng

), but one should at least strive to become a

junzi

, often translated as ‘gentleman’, but perhaps best thought of as meaning ‘a person of integrity’. Confucius looked back to the Zhou dynasty, a supposed ‘golden age’ which was long-past even during his lifetime, and which set a desirable (but perhaps unattainable) standard for the present day.

Confucius’s opinions did not emerge from thin air: he lived during the period of the Warring States, a violent era whose values appalled him, and which fuelled his concern with order and stability. Nor was he the only thinker to shape early China: unlike Confucius and Mencius, who believed in the essential good nature

hina

of human beings, Xunzi believed that humans were essentially evil; and Han Feizi went further to argue that only a system

Modern C

of strict laws and harsh punishments, not ethical codes, could restrain people from doing wrong. This period, the 5th century BCE, was one of profound crisis in the territory we know now as China, but ironically, it led to an unmatched excellence in the cultural and intellectual atmosphere of the time, just as the crisis of 5th-century BCE Greece led to an extraordinary outpouring of drama and philosophy. Nonetheless, despite the intellectual ferment of the time, it was Confucius’s thought that became most acceptable in Chinese statecraft, although his ideas were adapted, often beyond recognition, by the statesmen and thinkers who drew on his writings over the centuries. But throughout that period, assumptions from Confucianism persisted.

The premodern Chinese had a clear idea of a difference between themselves and other groupings, not least because there were frequent attacks by and on the neighbours. During two of China’s greatest dynasties, the Yuan and the Qing, the country was ruled 8

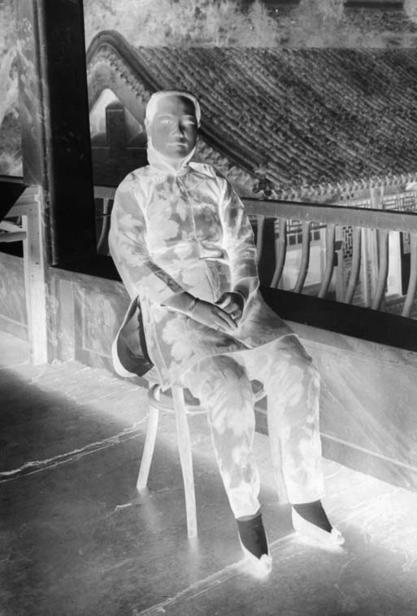

2. A wealthy Chinese woman in the early 20th century, with expensive

clothes and bound feet

9

by ethnic non-Chinese (Mongols and Manchus respectively).

However, the remarkable resilience of the Chinese system of statecraft meant that these occupiers soon adapted themselves to Chinese norms of governance, something that marked these invaders out from the Western imperialists, who did nothing of the sort. The assimilation was not total. The Qing aristocracy maintained a complex system of Manchu elite identity during their centuries of power: Manchus were organized in ‘banners’

(groupings based on their military nomadic past), and Manchu women did not bind their feet. But overall, the rituals and assumptions of Confucian ethics and norms still pervaded through society: Qing China was at core a Chinese, not a Manchu, society.

The 19th century saw a profound change in Chinese self-perception. For centuries, the empire had been termed

tianxia

, literally and poetically rendered as ‘all under heaven’. This did

hina

not mean that premodern Chinese did not recognize that there were lands or peoples that were not their own – they certainly

Modern C

did – but that the empire contained all those who mattered, and its border was fl exible, although not infi nitely elastic. (The Treaty of Nerchinsk, signed in 1689, drew up the border which still exists today between China and Russia; clearly Qing China did not lack a sense of territoriality.)

But the arrival of Western imperialism forced China, for the fi rst time, to think of itself as part of an international

system.

The arrival of European political thought brought to China the idea of the nation-state, and many Chinese came to terms with the fact that the old China was gone, and that the new one would need to assert its place in the hierarchy of nations. That struggle is still with us today.

Yet the modern People’s Republic does not contain the whole of China, or China’s worlds, within it. Taiwan provides an alternative, 10

lively and democratic vision of what ‘Chinese culture’ is; so does Hong Kong. Then there are diaspora Chinese: the ‘overseas Chinese’ who shape societies such as Singapore and whose communities are found on all inhabited continents.

China is a continent, not just a country. It is a series of identities, some shared, some differentiated, and some contradictory: modern, Confucian, authoritarian, democratic, free, and restrained. Above all, China is a plural noun.

What is modern?

Frequently, ‘modern’ is used as shorthand for ‘recent’ – so a study of ‘modern’ China would refer to its history over the last century or so. This book, however, will use a more specifi c defi nition of

What is modern C

‘modern’, because by doing so, it can get to the heart of some of the biggest questions that continue to face China today – the questions of what sort of society and culture it is, and wishes to become.

hina?

First, though, there are certain ways

not

to think about ‘modern’

China. When trying to defi ne the way in which China has changed since the 19th century, it is possible to fall into one of two overly broad explanations.

The fi rst explanation was more common a generation ago, when Mao was in power and China seemed utterly to have changed its political and social system. This argument followed the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s rhetoric of a ‘new China’ (although, as the quotation at the start of this chapter shows, this was not the fi rst nor last usage of the term ‘New China’): that the old,

‘feudal’, ‘traditional’, and ‘semicolonial’ China, a world of cruel social hierarchies, foot-binding, torture, and poverty, had been fi nally brushed aside for a more egalitarian, industrial, and just China.

11

The second explanation, common in the early 20th century, but banished for a while after 1949, has become commonplace again today. This argument is that China has not essentially changed. Even fi gures such as Mao and Deng Xiaoping (the reformist leader of the 1980s), despite their coating of communist ideology and mass mobilization politics, were essentially

‘emperors’ reverting to type. In the countryside today, traditional superstitions, religions (such as the Falun Gong cult banned by the party) and hierarchies reign supreme, just as they have done for hundreds of years. Overall, China remains a Confucian, hierarchical society with an ostensibly communist brand name on top.

These views are wrong. China is a profoundly modern society; but the way in which its modernity has been manifested is indelibly shaped by the legacy of its premodern (a term preferable to ‘traditional’) past. Not that the premodern past was ever

hina

monolithic or static: China changed immeasurably over hundreds of years, developing a bureaucracy, science, and technology

Modern C

(the invention of gunpowder, clocks, and the compass), a highly commercialized economy (from around 1000 onwards), and a diverse syncretic religious culture.

The similarity in many developments in Europe and China in the period 1000 to around 1800 should not, however, conceal the fact that imperial China and early modern Europe also

differed

widely in their assumptions and mindsets. The development of modernity in the Western world was underpinned by a set of assertions, many of which are still powerful today, about the organization of society. Most central was the idea of ‘progress’ as the driving force in human affairs. Philosophers such as Descartes and Hegel ascribed to modernity a rationality and teleology, an overarching narrative, that suggested that the world was moving in a particular direction – and that that direction, overall, was a positive one. There were several drivers of progress. One was the idea that dynamic change was a good thing in its own right: 12

in premodern societies, the force of change was often feared as destructive, but the modern mindset welcomed it. In particular, an acceptance and enthusiasm for progress through economic growth, and later, industrial growth, became central to the development of a modern society. Particularly in the formulation of the Enlightenment of the 18th century, the idea of rationality, the ability to make choices and decisions in a predictable, scientifi c way, also became crucial to the ordering of a modern society.

Modernity also altered the way in which members of society thought of themselves. Society was secularized: modernity was not necessarily hostile to religion, but religion was confi ned to a defi ned space within society, rather than penetrating through it. The individual self, able to reason, was now at the centre of

What is modern C

the modern world. At the same time, the traditional bonds that the self had to the wider community were broken down; modern societies did not support the old feudal hierarchies of status and bondage, but rather, broke them down in favour of equality, or at

hina?

any rate, a non-hierarchical model of society.

Above all, societies are modern in large part because they perceive themselves as being so: self-awareness (‘enlightenment’) is central to modernity and the identities that emerge from it, such as nationhood. This has led the West, in particular, to draw far too strong a distinction between its own ‘modern’ values and those elsewhere in the world. China, for instance, showed many features over thousands of years that shared assumptions of modernity long before the West had a signifi cant impact there. China used a system of examinations for entry to the bureaucracy from the 10th century CE, a clearly rational and ordered way of trying to choose a power elite, at a time when religious decrees and brute force were doing the same job in much of Europe. At the same time, China started to develop an integrated and powerful commercial economy, with cash crops taking the place of subsistence farming. It is clear that many 13

aspects of ‘modernity’ were visible earlier and more clearly in China than in Europe.