Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century (42 page)

Read Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century Online

Authors: Peter Watson

Tags: #World History, #20th Century, #Retail, #Intellectual History, #History

As well as being a classic middle American, Babbitt was also a typical ‘middlebrow,’ a 1920s term coined to describe the culture espoused by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). However, it applied a fortiori in America, where a whole raft of new media helped to create a new culture in the 1920s in which Babbitt and his booster friends could feel at home.

At this end of the century the electronic media – television in particular, but also radio – are generally regarded as more powerful than print media, with a much bigger audience. In the 1920s it was different. The principles of radio had been known since 1873, when James Clerk Maxwell, a Scot, and Heinrich Hertz, from Germany, carried out the first experiments. Guglielmo Marconi founded the first wireless telegraph company in 1900, and Reginald Fessenden delivered the first ‘broadcast’ (a new word) in 1906 from Pittsburgh. Radio didn’t make real news, however, until 1912, when its use brought ships to the aid of the sinking

Titanic.

All belligerents in World War I had made widespread use of radio, as propaganda, and afterwards the medium seemed ready to take America by storm – radio seemed the natural vehicle to draw the vast country together. David Sarnoff, head of RCA, envisaged a future in which America might have a broadcasting system where profit was not the only criterion of

excellence, in effect a public service system that would educate as well as entertain. Unfortunately, the business of America was business. The early 1920s saw a ‘radio boom’ in the United States, so much so that by 1924 there were no fewer than 1,105 stations. Many were tiny, and over half failed, with the result that radio in America was never very ambitious for itself; it was dominated from the start by advertising and the interests of advertisers. Indeed, at one time there were not enough wavelengths to go round, producing ‘chaos in the ether.’

17

As a consequence of this, new print media set the agenda for two generations, until the arrival of television. An added reason, in America at least, was a rapid expansion in education following World War I. By 1922, for example, the number of students enrolled on American campuses was almost double what it had been in 1918.

18

Sooner or later that change was bound to be reflected in a demand for new forms of media. Radio apart, four new entities appeared to meet that demand. These were

Reader’s Digest, Time,

the Book-of-the-Month Club, and the

New Yorker.

If war hadn’t occurred, and infantry sergeant DeWitt Wallace had not been hit by shrapnel during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, he might never have had the ‘leisure’ to put into effect the idea he had been brooding upon for a new kind of magazine.

19

Wallace had gradually become convinced that most people were too busy to read everything that came their way. Too much was being published, and even important articles were often too wordy and could easily be reduced. So while he was convalescing in hospital in France, he started to clip articles from the many magazines that were sent through from the home front. After he was discharged and returned home to Saint Paul, Minnesota, he spent a few more months developing his idea, winnowing his cuttings down to thirty-one articles he thought had some long-term merit, and which he edited drastically. He had the articles set in a common typeface and laid out as a magazine, which he called

Reader’s Digest.

He ordered a printing of 200 copies and sent them to a dozen or so New York publishers. Everyone said no.

20

Wallace’s battles to get

Reader’s Digest

on a sound footing after its launch in 1922 make a fine American adventure story, with a happy ending, as do Briton Hadden’s and Henry Luce’s efforts with

Time,

which, though launched in March 1912, did not produce a profit until 1928. The Book-of-the-Month-Club, founded by the Canadian Harry Scherman in April 1926, had much the same uneven start, with the first books, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s

Lolly Willowes,

T. S. Stribling’s

Teeftallow,

and

The Heart of Emerson’s Journals,

edited by Bliss Perry, being returned ‘by the cartload.’

21

But Wallace’s instincts had been right: the explosion of education in America after World War I changed the intellectual appetite of Americans, although not always in a direction universally approved. Those arguments were especially fierce in regard to the Book-of-the-Month Club, in particular the fact that a committee was deciding what people should read, which, it was said, threatened to ‘standardise’ the way Americans thought.

22

‘Standardisation’ was worrying to many people in those days in many walks of life, mainly as a result of the ‘Fordisation’ of industry following the invention of the moving assembly line in 1913. Sinclair Lewis

had raised the issue in

Babbitt

and would do so again in 1926, when he turned down the Pulitzer Prize for his novel

Arrowsmith,

believing it was absurd to identify any book as ‘the best.’ What most people objected to was the mix of books offered by the Book-of-the-Month Club; they claimed that this produced a new way of thinking, chopping and changing between serious ‘high culture’ and works that were ‘mere entertainment.’ This debate produced a new concept and a new word, used in the mid-1920s for the first time:

middlebrow.

The establishment of a professoriate in the early decades of the century also played a role here, as did the expansion of the universities, before and after World War I, which helped highlight the distinction between ‘highbrow’ and ‘lowbrow.’ In the mid- and late 1920s, American magazines in particular kept returning to discussions about middlebrow taste and the damage it was or wasn’t doing to young minds.

Sinclair Lewis might decry the very idea of trying to identify ‘the best,’ but he was unable to stop the influence of his books on others. And he earned perhaps a more enduring accolade than the Pulitzer Prize from academics – sociologists – who, in the mid-1920s, found the phenomenon of Babbitt so fascinating that they decided to study for themselves a middle-size town in middle America.

Robert and Helen Lynd decided to study an ordinary American town, to describe in full sociological and anthropological detail what life consisted of. As Clark Wissler of the American Museum of Natural History put it in his foreword to their book,

Middletowm,

‘To most people, anthropology is a mass of curious information about savages, and this is so far true, in that anthropology deals with the less civilised.’ Was that irony – or just cheek?

23

The fieldwork for the study, financed by the Institute of Social and Religious Research, was completed in 1925, some members of the team living in ‘Middletown’ for eighteen months, others for five. The aim was to select a ‘typical’ town in the Midwest, but with certain specific aspects so that the process of social change could be looked at. A town of about 30,000 was chosen (there being 143 towns between 25,000 and 50,000, according to the U.S. Census). The town chosen was homogeneous, with only a small black population – the Lynds thought it would be easier to study cultural change if it was not complicated by racial change. They also specified that the town have a contemporary industrial culture and a substantial artistic life, but they did not want a college town with a transient student population. Finally, Middletown should have a temperate climate. (The authors attached particular importance to this, quoting in a footnote on the very first page of the book a remark of J. Russell Smith in his

North America:

‘No man on whom the snow does not fall ever amounts to a tinker’s damn’)

24

It later became known that the city they chose was Muncie, Indiana, sixty miles northeast of Indianapolis.

No one would call

Middletown

a work of great literature, but as sociology it had the merit of being admirably clearheaded and sensible. The Lynds found that life in this typical town fell into six simple categories: getting a living; making a home; training the young; using leisure in various forms of play, art, and so forth; engaging in religious practices; and engaging in community

activities. But it was the Lynds’ analysis of their results, and the changes they observed, that made

Middletown

so fascinating. For example, where many observers – certainly in Europe – had traditionally divided society into three classes, upper, middle, and working, the Lynds detected only two in Middletown: the business class and the working class. They found that men and women were conservative – distrustful of change – in different ways. For instance, there was far more change, and more acceptance of change, in the workplace than in the home. Middletown, the Lynds concluded, employed ‘in the main the psychology of the last century in training its children in the home and the psychology of the current century in persuading its citizens to buy articles from its stores.’

25

There were 400 types of job in Middletown, and class differences were apparent everywhere, even at six-thirty on the average morning.

26

‘As one prowls Middletown streets about six o’clock of a winter morning one notes two kinds of homes: the dark ones where people still sleep, and the ones with a light in the kitchen where the adults of the household may be seen moving about, starting the business of the day.’ The working class, they found, began work between six-fifteen and seven-thirty, ‘chiefly seven.’ For the business class the range was seven-forty-five to nine, ‘but chiefly eight-thirty.’ Paradoxes abounded, as modernisation affected different aspects of life at different rates. For example, modern (mainly psychological) ideas ‘may be observed in [Middletown’s] courts of law to be commencing to regard individuals as not entirely responsible for their acts,’ but not in the business world, where ‘a man may get his living by operating a twentieth-century machine and at the same time hunt for a job under a

laisser-faire

individualism which dates back more than a century.’ ‘A mother may accept community responsibility for the education of her children but not for the care of their health.’

27

In general, they found that Middletown learned new ways of behaving toward material things more rapidly than new habits addressed to persons and nonmaterial institutions. ‘Bathrooms and electricity have pervaded the homes of the city more rapidly than innovations in the personal adjustments between husband and wife or between parents and children. The automobile has changed leisure-time life more drastically than have the literature courses taught the young, and tool-using vocational courses have appeared more rapidly in the school curriculum than changes in the arts courses. The development of the linotype and radio are changing the technique of winning political elections [more] than developments in the art of speechmaking or in Middletown’s method of voting. The Y.M.C.A., built about a gymnasium, exhibits more change in Middletown’s religious institutions than do the weekly sermons of its ministers.’

28

A classic area of personal life that had hardly changed at all, certainly since the 1890s, which the Lynds used as the basis for their comparison, was the ‘demand for romantic love as the only valid basis for marriage…. Middletown adults appear to regard romance in marriage as something which, like their religion, must be believed in to hold society together. Children are assured by their elders that “love” is an unanalysable mystery that “just happens.” … And yet, although theoretically this “thrill” is all-sufficient to insure permanent

happiness, actually talks with mothers revealed constantly that, particularly among the business group, they were concerned with certain other factors.’ Chief among these was the ability to earn a living. And in fact the Lynds found that Middletown was far more concerned with money in the 1920s than it had been in 1890. In 1890 vicinage (the old word for neighbourhood) had mattered most to people; by the 1920s financial and social status were much more closely allied, aided by the automobile.

29

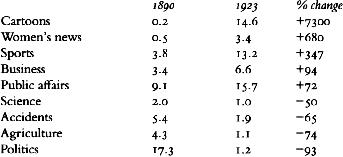

Cars, movies, and the radio had completely changed leisure time. The passion with which the car was received was extraordinary. Families in Middletown told the Lynds that they would forgo clothes to buy a car. Many preferred to own a car rather than a bathtub (and the Lynds did find homes where bathtubs were absent but cars were not). Many said the car held the family together. On the other hand, the ‘Sunday drive’ was hurting church attendance. But perhaps the most succinct way of summing up life in Middletown, and the changes it had undergone, came in the table the Lynds presented at the end of their book. This was an analysis of the percentage news space that the local newspapers devoted to various issues in 1890 and 1923:

30

Certain issues we regard as modern were already developing. Sex education was one; the increased role (and purchasing power) of youth was another (these two matters not being entirely unrelated, of course). The Lynds also spent quite a bit of time considering differences between the two classes in IQ. Middletown had twelve schools; five drew their pupils from both working-class and business-class parents, but the other seven were sufficiently segregated by class to allow the Lynds to make a comparison. Tests on 387 first-grade (i.e., six-year-old) children revealed the following picture:

31