Molon Labe! (83 page)

Authors: Boston T. Party,Kenneth W. Royce

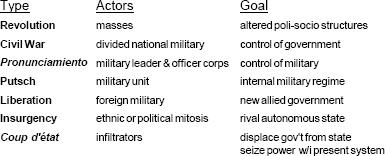

SO, WHAT DO WE CALL THIS THING?

We should classify along historical models the dynamics of Wyoming's governmental change. What will we have accomplished in 2014? A Revolution? A Civil War? A

Pronunciamiento

? A Putsch? A Liberation? An Insurgency? A

Coup

?

The answer is not merely semantic relief, but will illustrate more clearly the obstacles we must overcome.

DIAGNOSIS

The different varieties of upheavals are all distinct from each other, yet often share common characteristics.

For example, of the seven upheavals, at least three employ some elements of the domestic military forces as primary actors. This is not desirable for our purposes. Furthermore, the violence inherent to a Revolution, Civil Liberation, or Insurgency strikes them from candidacy.

This leaves one form of governmental change most similar to our plan: a

coup d'état.

The object of a

coup

is to seize power within the present political infrastructure by displacing government from the state.

A rigged election (with a nonviolent aftermath) has long served as one peaceful means of a

coup

.

Assassinations have also been catalysts for

coup

s. JFK's assassination in November 1963 has often been bitterly referred to as a

coup

which directly benefited the military and CIA by installing as President the pro-Vietnam War Lyndon Johnson.

HOW TO BAKE A

COUP

The seminal work on how to actually plan and execute a successful

coup d'état

is Edward Luttwak's

Coup d'état

, which was published in 1979. We shall quote from it extensively:

...

[T]

he

coup d' état

is now the normal mode of political change in most member states of the United Nations.

...

[During 1963 to 1978]

there have been some hundred and twenty military

coups

, whereas only five guerrilla movements have come to power — and three of these followed the Portuguese

coup

in 1974. The function of the guerrilla movement has reverted to what it originally was — that of paving the way for and supporting the regular army: it holds the stirrup so that others may get into the saddle.

...

[C]oups

...are still the only form of political change that can be envisaged at the present time.

— foreword to

Coup d' Etat

, Edward Luttwak (1979), p. 11

The

coup

is a much more democratic affair

(than a revolution)

. It can be conducted from the "outside" and it operates in that area outside the government but within the state which is formed by the permanent and professional civil service, the armed forces and police. The aim is to detach the permanent employees of the state from the political leadership, and this cannot usually take place if the two are linked by political, ethnic or traditional loyalties.

(at 20)

A

coup

consists of the infiltration of a small but critical segment of the state apparatus, which is then used to displace the government from its control of the remainder.

(at 27)

If we were revolutionaries, wanting to change the structure of society

(through warfare)

, our aim would be to destroy the power of the political forces, and the long and often bloody process of revolutionary attrition can achieve this.

Our purpose is, however, quite different: we want to seize power within the system

, and we shall stay in power if we embody some new

status quo

supported by those very forces which a revolution may seek to destroy. Should we want to achieve a fundamental social change we can do so after we have become the government. This is perhaps a more efficient method (and certainly a less painful one) than that of classic revolution.

Though we will try to avoid all conflict with the "political" forces, some of them will almost certainly try to oppose a

coup

. But this opposition will largely subside when we have substituted our new

status quo

for the old one, and can enforce it by our control of the state bureaucracy and security forces. This period of transition, which comes after we have emerged into the open and before we are vested with the authority of the state, is the most critical phase of the

coup. (at 58)

— Edward Luttwak,

Coup d' Etat

(1979)

Preconditions of the

Coup

A) Political participation confined to a small fraction of the population

(Little/no dialogue between government and people.)

B) Target state must be mostly independent from foreign powers

C) Target state must have a political center

Factors which weaken developed countries:

A) Severe and prolonged economic crisis, with widespread unemployment and/or hyperinflation

B) A long, unsuccessful war or a major defeat (military or diplomatic)

C) Chronic instability under a democratic system

Example: 1958 France (IVth Republic)

SECESSION

...Whenever any form of government becomes destructive to these ends

(of liberty)

it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it...

— American Declaration of Independence, 1776

Most damaging of all was the fact that while an early draft of the Constitution had specified that "the Union shall be perpetual,"

the phrase had been dropped prior to adoption of a final document.

— Daniel Lazare;

The Frozen Republic

, p. 104

State after state made it clear that they were joining the Union

voluntarily

, without relinquishing their sovereignty. For example, Virginia's ratification resolution specified

"that the powers granted under the Constitution being derived from the People...may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression."

Madison had to admit, in

The Federalist

#39, that

"each State, in ratifying the Constitution, is considered as a sovereign body independent of all others, and only to be bound by its voluntary act."

The early history of secession in America

There have been three successful secession movements in America. One was the Declaration of Independence and the founding of the Articles

[of Confederation]

. The second was the U.S. Consitution itself, whereby the states seceded from their original compact (the Articles). The third was the Confederate secession, that was successful, but militarily overturned.

— from an Internet thread on secession, 27 November 2000

A state's nullification of acts considered unconstitutional or unlawful is to protect its rights within the Union. Nullification was not solely a Southern act. Massachusetts nullified the fugitive slave law and threatened to secede before complying with a Supreme Court ruling.

A state's secession is a forced necessity to protect its rights which can no longer be maintained within the Union. Secession was not originally or solely a Southern idea. It was the New England states which, on several occasions, seriously discussed leaving the Union.

In 1794, Senators Rufus King (N.Y., also a 1787 Philadelphia delegate) and Oliver Ellsworth (Conn.) approached Senator John Taylor (Va.) to discuss a peaceful dissolving of the Union because

"the southern and eastern people thought quite differently."

After the 1800 election of Thomas Jefferson as President, which horrified the federalists, New England threatened to secede. (Alexander Hamilton's influence barely prevented New York from going along, which foiled the plan.) Jefferson's attack on the federalist judiciary, however, kept the secession coals smoldering.

If there be any among us who wish to dissolve the Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed, as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.

— Thomas Jefferson, 1801, from his first inaugural address

The coals flared up over the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, which enlarged the sphere of the South, as well as Jeffersonian appeal. Massachusetts Senator Timothy Pickering claimed that the northern confederacy would be

"exempt from the corrupt and corrupting influence and oppression of the aristocratic democrats of the South."

The principles of our Revolution

[of 1776]

point to the remedy — a separation, for the people of the East cannot reconcile their habits, views, and interests with those of the South and West.

— Timothy Pickering, leader of the New England secessionists, in an 1803 letter to George Cabot

The Eastern states must and will dissolve the Union and form a separate government.

— Senator James Hillhouse, 1803

Again, Hamilton was against secession. In what was to be his last letter, written to Theodore Sedgwick (one of the leading Massachusetts Federalists) the night before his 11 July 1804 duel with Vice President Aaron Burr, Hamilton wrote,

"Dismemberment of our Empire will be a clear sacrifice of great positive advantages, without any counterbalancing good....

[Secession would provide]

no relief to our real disease; which is DEMOCRACY."

Jefferson's Trade Embargo and Madison's War of 1812

The ruinous effect on New England of Jefferson's 1808 trade embargo with Britain and France kept Eastern resentment alive until the next catalyst, the War of 1812 and President Madison's Virginian policies. Hence, the Hartford Convention in January 1815 (convened by the "Essex Junto"). The British had already landed 4,100 troops and sacked Washington, D.C., causing President Madison and the First Lady to flee to Virginia.

There are not two hostile nations upon earth whose views of the principles and polity of a perfect commonwealth, and of men and measures, are more discordant than those of these two great divisions.

— from a pro-secessionist Northern manifesto, just prior to the War of 1812

[The 1789 Union was]

the

means

of securing the safety, liberty, and welfare of the confederacy

[of 1781]

,

and not itself an end to which these should be sacrificed.

— John Randolph in 1814

While the New Englanders were discussing regional secession in Hartford, Major General Andrew Jackson routed the British invasion of New Orleans. News of Jackson's victory rescued Madison's administration and doomed the New England secessionist movement.

In no instance was it ever supposed that the states, which had joined the Union from their sovereign capacity, could not choose to quit the Union from that same sovereign capacity. The irony to appreciate here is that for the first twenty years of our constitutional history, it was the

creators

of that very constitution — the Federalists —who simmered with secession.

The moral? If the Federalists of 1794 to 1815 — which included several personalities present at the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 —saw no constitutional barriers to secession,

then how can anybody else

?

Leading up to the War Between the States

It depends on the state itself to retain or abolish the principle of representation, because it depends on itself whether it will continue as a member of the Union. To deny this right would be inconsistent with the principle on which all our political systems are founded, which is, that the people have in all cases, a right to determine how they will be governed.

This right must be considered as an ingredient in the original composition of the general government, which, though not expressed, was mutually understood...