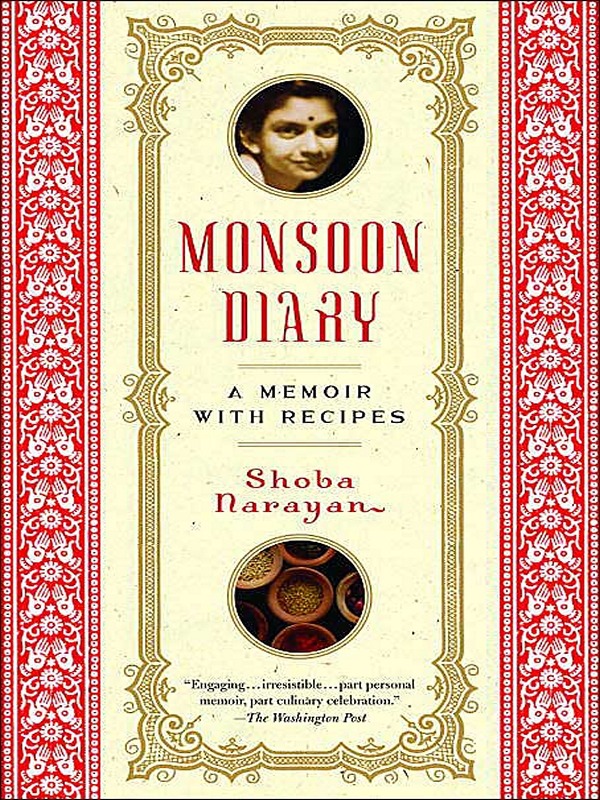

Monsoon Diary

Authors: Shoba Narayan

Tags: #Cooking, #Memoirs, #Recipes, #Asian Culture, #India, #Nonfiction

Table of Contents

THREE - Sun-Dried Vegetables on the Roof

NINE - A Feast to Decide a Future

TWELVE - Creation of an Artist

THIRTEEN - Summer of Bread and Music

SEVENTEEN - Honeymoon in America

To my parents,

Professor V. R. Narayanaswami

and

Mrs. Padma Narayanaswami

Praise for

Monsoon Diary

“[The recipes] are uniformly inviting—indeed a minor difficulty about this book is that it provokes a pronounced surge of the appetite. . . .

Monsoon Diary

is the first book [Narayan] has written, but doubtless not the last.”

—JONATHAN YARDLEY,

The Washington Post

“Narayan, who grew up in Chennai, India, writes in humorous, tender prose about her family and their love of food. . . . Narayan’s sparkling, insightful narrative makes for a delightful cultural and culinary read.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“Weaving together stories from her remarkable life with tasty Indian vegetarian recipes, Narayan offers insights into Hindu culture and custom and contrasts her upbringing with life in her adopted America. . . . This is a delightful, stereotype-shattering memoir.”

—MARK KNOBLAUCH,

Booklist

“Shoba Narayan is that rarity in the food world: She has both a unique story and the lyrical skills to tell it.”

—REGINA SHRAMBLING,

New York Times

and

Los Angeles Times

food writer

“A taste of a life that is exotic yet familiar,

Monsoon Diary

is as pungent and satisfying as a good curry. Reading it made me want to get on a plane to India—or at least eat in an Indian restaurant.”

—SHARON BOORSTIN,

author of

Let Us Eat Cake:

Adventures in Food and Friendship

Acknowledgments

WHEN WRITING a first book, it is tempting to acknowledge everyone who has meant something to you in case you never write another. I will refrain from doing that and confine my acknowledgments to those people who have helped me with

this

book.

This book is dedicated to my parents. Like gentle if somewhat harried shepherds, they have steered my brother and me through our chaotic lives.

My mother always believed in my writing. More important, she made me believe that I was a writer, a good one at that. Without the strength of her conviction, I could not have written this book. She has been an incredible role model and one of the biggest influences on my life and character.

My father bequeathed to me his love for the English language, instructed me numerous times to “pick up the dictionary,” and trained his meticulous eye over my words, but only when I asked him to. He has always accepted and loved me even when I was a foulmouthed, rebellious brat whom even I couldn’t stand.

Most people experience an epiphany of sorts when they become parents. Mine was to realize how tricky parenting is, and what my parents must have gone through to raise us. After obeying them, resenting them, and rebelling against them, I have come full circle into enjoying them for who they are, quirks and all. Together they have been the sail and ballast to my ship. I have always loved them. Only recently have I started cherishing them. I hope all of this comes through in this book.

This book would never have come into being without the support and assistance of many people.

Professor Sam Freedman of the Columbia Journalism School taught me everything I know about the book-writing process. I hope I can live up to the standards he set.

In her incarnation as the

New York Times

restaurant critic, Ruth Reichl sowed the seeds of my career in food writing. As editor in chief of

Gourmet

magazine, she has continued her support. To her, I owe a debt of gratitude.

Elizabeth Kaplan championed my writing attempts and was my agent for this book. Her enthusiasm and encouragement have sustained me.

Pamela Cannon took a bet on this book and was its first cheerleader.

Mary Bahr, my editor, shaped this book with grace and charm. She knew when to cheer me on and when to let me be. Her instinct and guidance were right on target.

My brother, Shyam, is an unwitting character in this book. He has enriched my life in ways big and small—even if I didn’t think so as a child. I rely on him always.

My husband, an intensely private man, had the generosity of spirit to let me write about our marriage for the sake of this book and, by default, my career. His combination of cheerleading and critiquing has made me a better writer and a better person.

From the beginning, my in-laws, Padma and V. Ramachandran, have treated me like a daughter. I have asked them numerous questions about multiple subjects at moments when they least expected it. I am lucky to have their knowledge, wisdom, love, and support.

In the company of my two sisters-in-law, Lakshmi Krishnan and Priya Sunder, I have experienced the delights of sisterhood, something that I missed as a child. The recipes included in this book have benefited from their input and careful eye.

I would also like to thank Sybil Pincus at Random House for her attention to detail; my friend Asha Ranganathan for information about restaurants in Bombay; my Manhattan book group for helping me enjoy books, food, and martinis once a month; Janice Tannin for testing the recipes; Ann La Rue for her unqualified support in all my projects, including this one; Dave Matlow for his editorial eye and the “Shoba file”; my neighbors Prabha-mami, Nagarajan-Mama, Sumathi-ka, Babu-anna, Vijaya-aunty, and Nithya-uncle for giving me happy childhood memories, many of which I have written about in this book; my uncle V. R. Krishnamoorthy and aunt Lakshmi for letting us run riot through their house all summer long; my uncle T. V. Venkateswaran and cousin Sanjay Monie for lending photos from their archives; my uncle T. V. Raghuraman for his memoirs; Chhokpa and Mary for helping me in ways too numerous to list.

Writing, or, for that matter, any creative enterprise, involves the hubris of taking oneself seriously, sometimes too seriously. Last, I would like to break my rule and acknowledge two individuals who had very little to do with this book but helped immeasurably in preventing me from getting too self-involved. Like all children, my daughters, Ranjini and Malini, live with an intensity that is hard to ignore. Their smiles and demands did more than distract me from the computer; they gave me perspective.

To all those whom I have inadvertently left out, I offer my apologies and the promise: in my next book.

Prologue

FOR ONE WHO EATS so little, my father has an unquenchable fascination with food. A petite, lithe man with the curiosity of an inventor and the conflicted soul of an artist, he loves to try new things—in small doses, at his own pace.

When he first visited me as a newlywed in America, he spent the entire winter making up an alphabetized list of all the foods he had never tried, and systematically went about trying them. He started with avocadoes, which are unknown in tropical South India, and quickly moved on to anise candy, chipotle peppers, Etorki cheese, Fig Newtons, Kettle chips, molasses, quince, tomatillos,

zahtar,

and everything in between.

We never knew what he would come back with when he visited the grocery store. Once he bought a whole case of persimmons, which, he informed us, belonged to the genus

Diospyros

and meant “fruit of the Gods.” I considered myself an adventurous eater, but I had never tried a persimmon before. My husband, self-confessedly finicky, viewed the orange fruits with suspicion. Not wanting to hurt the feelings of his visiting father-in-law, he took a tentative bite and puckered his face. My mother and I followed my husband’s example and experienced the same reaction. Even one persimmon was too hard, tart, and astringent to be palatable. What were we going to do with twelve of them?

The next day I woke up to find a plate of invitingly cut persimmons dusted with sugar. Beside it was a typed recipe for Persimmon Rice Pudding. Persimmons have more vitamin C than oranges, my father said. They are an excellent source of potassium and beta-carotene. The fruit was unripe yesterday, he said, and therefore astringent. “The ripe persimmon tastes like an apricot,” he quoted from a Web site.

His next question: “What is an apricot?”

ONE

First Foods

THE FIRST FOODS that I ate were rice and ghee. I know this because my mother told me so. I was six months old, and as was traditional, my parents conducted a formal

choru-unnal

ceremony at the famous Guruvayur temple in Kerala.

Choru-unnal

literally means “rice-eating,” and the ceremony marks the first meal of a child. Typically, this is done in the presence of a priest who recites Sanskrit mantras while the parents, grandparents, and relatives tease morsels of mashed rice into the child’s mouth. Few Indians speak Sanskrit anymore, and most don’t understand what the mantras mean. Since the mantras are considered sacred, it is presumed that they will nudge the baby into a lifetime of healthful eating. This particular presumption must be wrong, for I know of no Indian child with good eating habits.

Indian mothers are obsessed with feeding their children, and perhaps as a result Indian kids don’t eat well. When I attend parties with American families, mealtimes seem so civilized and quiet. The mothers cut up a piece of meat or a pizza into small pieces, and the kids obligingly fork it in.

Compare that with an Indian party. Mothers follow their kids around, hands outstretched with food, entreating them to eat. Fathers balance plates of food in one hand and, with the other, try to grasp crawling babies intent on escaping. Clearly, the sacred mantras have not made one iota of difference in the children’s attitude toward food. Still, having a chanting priest at any Hindu rite of passage is de rigueur, and my family, traditional as it was, complied.

My parents had chosen the Krishna temple at Guruvayur for reasons both practical and sentimental. They each had had their own rice-eating ceremony there. The temple’s central location made it convenient for my grandparents, aunts, and uncles to attend. More important, my parents liked the “pure” ambience of the temple, which admitted only Hindus into its portals, and only those that followed its strict dress code. The women had to wear saris, and the men had to remove their shirts as a mark of respect for the deity. My parents were especially delighted by the fact that the temple kept out all foreigners, even those camera-toting tourists who thought they could gain admission into ancient temples by waving a few dollars. While such bribes may have worked in other temples, not so in Guruvayur, they remarked approvingly.

On the practical side, my father had vowed to conduct a

thula

bharam

at the temple to give thanks for my safe delivery. My parents thought that they could accomplish both events—the

choru-unnal

and the

thula bharam—

with one trip.

The

thula bharam

is an offering to God. In a corner of the temple was a giant scale (

thula

), behind which was a blackboard that listed various offerings: bananas, jaggery (unprocessed raw sugar), gold, silver, coconuts, and even water. Devotees could pick any one of the offerings, weigh themselves against it, and pay by the kilo for their choice.

Corrupt politicians would sit on one scale, while the temple staff loaded up the other with silver. When the scales were balanced, the politician would pay for his weight in silver and hope to wash away his sins. Corpulent gold merchants from Bombay—and they were almost always corpulent—would sit placidly on one scale and pay for the equivalent weight of gold with “black money” that didn’t make it to their tax books. Poor people who could afford little else would weigh themselves against water and pay their pittance to God, who, we children were told, viewed every offering with a benevolent eye. My father, a college professor just embarking on his career, sensibly chose bananas, which were in the middle of the price chart, above water, jaggery, and coconuts but much below gold and silver. He weighed himself against a bunch of bananas and paid for his

bharam

(weight).

The

choru-unnal

ceremony was next. All these religious rites were conducted in the outer sanctum, a vast space with cobblestone floors, granite walls, and carved pillars. Women in pristine white saris and dripping wet hair circled the temple muttering prayers; wandering mendicants with matted hair and saffron robes hobbled around; schoolchildren smeared sandalwood paste on their foreheads and chased one another from pillar to post. Against this busy backdrop, my family adjourned to a corner where I was to be fed for the first time. My grandmother held me in her lap while my parents converged around and made faces at me. I know this because it is what parents do when confronted with their newborn child.

A baby can do something as mundane as stick her tongue out and the proud parents will read profound meaning into the action. “Look, she is sucking her lips in anticipation of the food,” they will say.

Grandparents go a step further; they view the baby’s actions as a reflection of their gene pool. “After all, she is my granddaughter,” they will say. “Of course she knows that food is coming.”

The priest solemnly placed a sliver of ghee rice in my mouth. I promptly spat. Everyone went still.

“Let me taste the food,” my mother demanded. She did so and pulled a face. “The ghee is burnt,” she said. “No wonder my daughter spit up.”

The priest began to protest, but my family would have none of it. Their first child wasn’t going to eat burnt food for her first meal. The temple would kindly make some fresh ghee for the infant’s meal. They would be happy to wait.

So we waited. My parents gazed adoringly at me as I blew bubbles with my spit. The priest swatted flies. My grandparents tried to get their brand-new camera, bought for the occasion, to work. Temple officials arrived and informed my parents that they had tested the ghee and it wasn’t burnt, but they were going to make a fresh batch because my parents had insisted. Of course it would cost them double.

Half an hour later, fresh ghee arrived. The priest mixed it with rice, my mother tested it and slipped it into my mouth. This time I rolled it around with my tongue. My parents watched anxiously.

Another idea that afflicts new parents is the notion that their newborn is never wrong.

“See?” my mother remarked triumphantly when I eventually swallowed. “It wasn’t my daughter’s fault. It was the food.”

I rest my case.

I VISITED MANY TEMPLES as a child, mostly because my parents dragged me to them. Like all children, I viewed religion as a chore, a necessary hindrance that punctuated my beatific existence with its endless choices and boundless confidence. It is only recently that I have turned to religion for solace and sustenance. This, I suppose, is the process of growing up, of pondering life’s imponderables and acknowledging one’s limitations.

As a child, after a long morning of prostrating myself before multiple deities, I would stand in line for the

prasadam—

food that is presented to God and then distributed to the devotees—which in my mind was the best part of the visit. Each temple had a specialty. The Tirupati temple, where devotees shaved their hair and offered it to God as a symbol of their vanity, made excellent

laddus

(candied balls). The Guruvayur temple served thick

payasam,

a gooey combination of rice, milk, and sugar stirred slowly over an open fire by Brahmin priests until it turned light yellow. The Muruga temple in Palani was known for its

panchamritham

(five nectars), made with crystal sugar, honey, ghee, cardamom, and bananas. Some temples distributed sweet

pongal

folded within banana leaves. Others, a mixture of raisins, nuts, and coconut flakes. All of them used copious quantities of ghee.

Ghee (clarified butter) is one of the most highly regarded foods in Indian cuisine. While modern Indians dismiss it as being “fatty,” the ancients used to drink a teaspoon of warm ghee with every meal.

It is one of the easiest things to cook, but also the easiest to mess up. Making ghee is all about timing. The trick is to remove it from the fire at the exact moment when it turns golden brown. A minute extra could turn it black and imbue it with a burnt smell. Removing it from the fire early gives it a raw, buttery flavor, instead of the distinct fragrance of fresh ghee. Once the ghee is poured out, all that remains are its black dregs at the bottom of the pan.

As children, we would mix hot rice with the black dregs and gobble it down. This “black rice” had the flavor and taste of ghee and was also an Indian method of not wasting even a single ounce of the precious butter from which ghee is made.

A mixture of equal parts ghee, crushed fresh ginger, and brown sugar is an age-old recipe believed to improve digestion.

GHEE

Ghee is the vegetarian’s caviar: slightly sinful, somewhat excessive, but oh so delicious. For Indians, ghee offers the same rich— if guilty—pleasures that chocolates do for the dieter. My sister-in-law Priya is known far and wide as an exceptional cook. She says that just a teaspoon of ghee makes all the difference in flavor—like ice cream versus fat-free sorbet. While Indians may skimp on ghee in their daily life, they go overboard when it comes to ghee sweets.

Bus travel through Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and most other North Indian states affords the particular pleasure of eating hot rotis (flat breads) made right before one’s eyes at tiny roadside stalls and served on banyan leaves with a dash of hot ghee on top. These rotis are made from different grains

—bajra, jowar, ragi—

each with its own distinctive taste. But they are all topped with ghee.

Ghee keeps at room temperature for about two months, longer in the winter. It should be used like a condiment, in small quantities. Indians typically brush ghee on their breads, spoon it into rice, or stir it into their soups.

MAKES ABOUT 1/2 CUP

2 sticks (1 cup) unsalted butter, cut into 1-inch pieces

Bring butter to a boil in a small heavy saucepan over medium heat.

Once foam completely covers the butter, reduce the heat to very low. Cook, stirring occasionally, until a thin crust begins to form on the surface and milky white solids fall to the bottom of the pan, about 8 minutes.

Continue to cook, watching constantly and stirring occasionally to prevent burning, until the solids turn light brown and the butter deepens to golden and turns translucent and fragrant, about 3 minutes.

When the ghee stops bubbling, you can safely assume that it’s done. Remove it from the heat, let it cool, and pour it into a jar.