Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (36 page)

Read Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power Online

Authors: Robert D. Kaplan

Tags: #Geopolitics

Sawbawh Pah, fifty, a small, stocky man with a tuft of hair on his scalp, ran a clinic for wounded soldiers and people uprooted from their homes, of which there have been 1.5 million in Burma. With three thousand villages razed in Karen State alone, the

Washington Post

calls Burma a “slow-motion Darfur.”

1

Pah told me, with a simple, resigned expression, “My father was killed by the SPDC [State Peace and Development Council, the Burmese junta]. My uncle was killed by the SPDC. My cousin was killed by the SPDC. They shot my uncle in the head and cut off his leg while he was looking for food after the village was destroyed.” During a meal of fried noodles and eggs, in which a toilet roll substituted for napkins, I was inundated with life stories like Pah’s whose power lay in their grueling repetition.

Major Kea Htoo, the commander of the local battalion of Karen guerrillas, had reddened lips and a swollen left cheek from chewing betel nut his whole life. He saw his village burnt, along with his family’s “paddy,” or rice. “They raped the women, they killed the buffalo.”

They

were the SPDC or, if the event occurred before 1997, the SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council), the menacing acronym by which the Burmese junta previously was known. He, like the others I met, including the four with missing limbs, all told me that they saw no end to the war. They were not fighting for strictly a better regime in Burma, composed of more enlightened military officers, nor for a democratic government that would likely be led by ethnic Burmans like Aung San Suu Kyi, but for Karen independence. Tu Lu, missing a leg, had been in the Karen army for twenty years. Kyi Aung, the oldest at fifty-five, had been fighting for thirty-four years. These guerrillas were paid no salaries. They received only food and basic medicine. Life for them had been condensed to a

seemingly unrealistic goal of independence, mainly because nobody since Burma first fell under military misrule in 1962 had ever offered them anything resembling a compromise.

For the moment, the war in Burma was on an exceedingly low boil, with the military junta trapping the Karens, Shans, and other ethnics into small redoubts of territory near the Thai border. Yet the regime, beset by its own problems—a corrupt and desertion-plagued armed forces—seemingly lacked the strength for the final kill. And the ethnics were tough, with a strong sense of historical identity that had little connection to the Burmese state. So they tried to fight on.

Burma’s agony could be reduced to the singular inconsequential fact that because of endless conflict and gross, regime-inflicted underdevelopment, it is still sufficiently primitive to maintain an aura of romance. Thus, it joins Tibet and Darfur in a trio of

causes

, whose moral urgency in each case is buttressed by an aesthetic fascination for its advocates in the post-industrial West. In 1952 the British writer Norman Lewis published a book about his travels throughout Burma,

Golden Earth

, a spare and haunting masterpiece in which the insurrections of the Karen, Shan, and other hill tribes hover in the background, helping to make the author’s travels dangerous and, therefore, extremely uncomfortable. Only a small region in the north, inhabited largely by the Kachin, was “completely free of bandits or insurgent armies.” He spent a night tormented by rats, cockroaches, and a scorpion, yet woke none the worse in the morning to the “mighty whirring of hornbills flying overhead.” Indeed, his bodily sufferings were a small price to pay for the uncanny monochromatic beauty of a country of broken roads and no adequate hotels where “the condition of the soul replaces that of the stock markets as a topic for polite conversation.”

2

What is shocking about this more-than-half-century-old book is how contemporary it seems. Think of all the places where because of globalization even a ten-year-old travel book is already out of date.

But Burma is more than a place for which to feel sorry. And its ethnic struggles are of more than obscurantist interest. For one thing, with a third of the country’s population composed of ethnic minorities in its friable borderlands—accounting for seven of Burma’s fourteen states—the demands of the Karens and other minorities truly will come to the fore once the regime does collapse. Democracy will not solve Burma’s dilemma of being a mini-empire of nationalities, even if it does open the

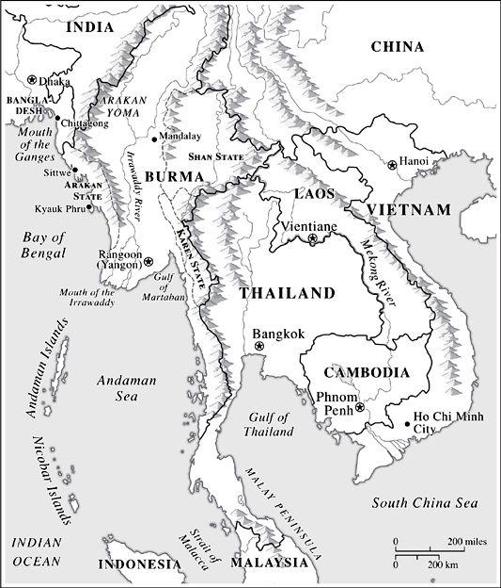

door to a compromise. More than that, however, Burma’s hill tribes are part of a new and larger canvas of geopolitics. Burma fronts on the Indian Ocean, by way of the Bay of Bengal. It is bordered by India and China, both of which covet Burma’s abundant reserves of oil, natural gas, uranium, coal, zinc, copper, precious stones, timber, and hydropower. China, especially, desires Burma as a vassal state for the construction of deep-water ports, highways, and energy pipelines that will provide China’s landlocked south and west access to the sea, from where China’s ever-burgeoning middle class can receive deliveries of oil from the Persian Gulf. And these routes must pass from the Indian Ocean north through the very territories plagued historically by Burma’s ethnic insurrections.

In short, Burma provides a code for understanding the world to come. It is a prize to be fought over, as China and India are not so subtly doing. Recognizing the importance of what Burma and its neighbors represent at a time of new energy pathways, unstable fuel prices, and seaboard natural disasters like Burma’s 2008 cyclone and the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, the U.S. Navy has suggested that it will no longer be forward-deployed permanently in the Atlantic, but instead will concentrate in the coming years and decades on the Indian Ocean and western Pacific. For the navy and the marine corps, too, Indian Ocean states like Burma are now, or should be, central to their calculations.

Strategic, romantic, and a moral catastrophe, Burma is a place that tends to consume people. And a very interesting group of Americans are consumed by it. In some cases, I cannot identify them by name, because of the tenuousness of their position in neighboring Thailand, which they use as a base (and where I interviewed them); in other cases, because of the sensitivity of what they do and for whom they work. But their story is worthwhile to tell because of the expertise they bring to bear, and what their own goals say about the geopolitical stakes in Burma.

Lately, it has become fashionable to extol the virtues of cultural area expertise given how the lack of it contributed to the mess in Iraq, even as it is forgotten that America’s greatest area experts have been Christian missionaries. American history has seen two strains of missionary-area experts, the old Arab hands and the Asia, or China, hands. The Arab hands were Protestant missionaries who traveled to Lebanon in the early nineteenth century and ended up founding what was to become the American University in Beirut. From their lineage descended the State

Department Arabists of the Cold War era. The Asia hands have a similarly distinguished origin, beginning, too, in the nineteenth century and providing the U.S. government with much of its area expertise through the early Cold War, when a number of them were unjustly purged during the McCarthy-era hearings on China. The American who counseled me on Burma was the descendant of several generations of Baptist missionaries from the Midwest who ministered to the Burmese hill tribes beginning in the late nineteenth century, particularly in the Shan States and across the Chinese border in Yunnan. His father was known as the Blue-eyed Shan. Escaping Burma on the heels of the invading Japanese, his father was conscripted into Britain’s Indian Army in which he commanded a Shan battalion during World War II. Thus, my acquaintance had grown up in India and postwar Burma. Among his earliest memories was the sight of Punjabi soldiers ordering work gangs of Japanese prisoners of war to pick up rubble in the Burmese capital of Rangoon. With no formal education, he spoke Shan, Burmese, Hindi, Lao, Thai, and the Yunnan and Mandarin dialects of Chinese. He had spent his life studying Burma, though the 1960s saw him elsewhere in Indochina aiding America’s effort in Vietnam.

During our first conversation he sat erect and cross-legged on a raised platform, wearing a traditional Burmese

longyi

in his home. He was gray haired, with a sculpted face and an authoritative Fred Thompson voice that gave him a courtly bearing: very much the wise elder statesman tempered by a certain oriental gentleness. Around him were a few books and photos: of butterfly wings, of the king and queen of Thailand, and of himself as a muscular young man with a bandolier and machete in Vietnam.

“Chinese intelligence is beginning to operate with the anti-regime Burmese ethnic hill tribes,” he told me. “The Chinese want the dictatorship in Burma to remain, but being pragmatic, they also have alternative plans for the country. The warning that comes from senior Chinese intelligence officers to the Karens, the Shans, and other ethnics is ‘to come to us for help—not the Americans—since we are next door and will never leave the area.’ ”

At the same time, he explained, the Chinese were beginning to reach out to young military officers in Thailand. In recent years, the Thai royal family and the Thai military, particularly the special forces and cavalry, have been sympathetic to the hill tribes fighting the pro-Chinese military junta in Burma; whereas Thailand’s civilian politicians, influenced by

various lobbies wanting to do business with resource-rich Burma, have been the junta’s best allies. In sum, democracy in Thailand has been at times the enemy of democracy in Burma.

But the Chinese, he implied, are still not satisfied: they want

both

Thailand’s democrats and military officers on their side, even as they work with

both

Burma’s junta and its ethnic opponents. “A new bamboo curtain may be coming down on Southeast Asia,” he worried. If such a thing were to happen, it would not be a hard and fast wall like the iron curtain; nor would it be part of some newly imagined Asian domino theory, similar to what was believed in the Vietnam era. Rather, it would be a discreet zone of Chinese political and economic influence fostered by, among other factors, relative American neglect, which was somewhat the case during the administration of George W. Bush. While the Chinese are operating at every level in Burma and Thailand, top Bush administration officials had periodically missed summits of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). And while China has launched twenty-seven separate ASEAN-China mechanisms in the past decade, the U.S. has launched only seven in thirty years.

3

My friend wanted the U.S. back in the game. And thus far the Obama administration has obliged him.

*

“To topple the regime in Burma,” he said, “the ethnics need a full-time advisory capability, not in-and-out soldiers of fortune. This would include a coordination center inside Thailand. There needs to be a platform for all the disaffected officers in the Burmese military to defect to.” Again, rather than a return to the early Vietnam era, he was talking about a more subtle and clandestine version of the kind of support the U.S. provided the Afghan mujahidin fighting the Soviets from bases inside Pakistan during the 1980s. The pro-Karen Thai military could yet return to power in Bangkok, and even if it did not, if the U.S. signaled its intent to provide serious support to the Burmese hill tribes against a regime hated the world over, the Thai security apparatus would find a way to assist.

“The Shans and the Kachins near the Chinese border,” he went on, “have gotten a raw deal from the Burmese junta, but they are also nervous about a dominant China. They feel squeezed. And unity for the hill

tribes of Burma is almost impossible. Somebody from the outside must provide a mechanism upon which they can all depend.”

Burma should not be confused with the Balkans, or with Iraq, where ethnic and sectarian differences simmering for decades under a carapace of authoritarianism erupted once central authority dissolved. The hill tribes have been at war with successive Burmese regimes for decades. War fatigue has set in, and the tribes show little propensity to fight one another were the regime to unravel. They are more disunited than they are at odds. Even among themselves, as he told me, the Shan have been historically subdivided into states led by minor kings. Thus, there might be a quiet organizing role for Americans of his ilk.

He mentioned Singapore leader Lee Kuan Yew’s warning that the U.S. must stay engaged in the region as a “counterbalance to the Chinese giant”; the U.S. being the only outsider power with the wherewithal to slow down Beijing’s advance, even though it has no territorial designs of its own in Asia. Southeast Asian nations in general, and Vietnam in particular, with its own historic fear of China, wanted Washington to counter Beijing in Burma. Thailand, with a monarchical succession ahead of it that could usher in an era of unstable politics, fears falling further under Chinese influence. Not even the Burmese junta, my friend said, wanted to be part of a Greater China. There are memories still of the long, grueling, and bloody Manchu invasion in the eighteenth century. It is just that the Burmese generals have had no choice, if they want to remain in power.