Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (40 page)

Read Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power Online

Authors: Robert D. Kaplan

Tags: #Geopolitics

“It’s much more complicated than the ‘beauty and the beast’ scenario put forth by some in the West—Aung San Suu Kyi versus the generals,” said Lian Sakhong. “After all, we must end sixty years of civil war.”

In sum, Burma must find a way to return to the spirit of the Panglong Agreement of 1947, which provided for a decentralized Union of Burma. Unfortunately, the agreement was never implemented, and thus was the cause of all the problems since.

Even within the central Irrawaddy valley and delta, away from the hill tracts, large Karen and Mon minorities demand equality with the Burmans, promised to them by Aung San before he was assassinated. While the world demanded relief assistance for the delta inhabitants worst affected by Cyclone Nargis in May 2008, the generals, who in any case have little regard for the Karens living there, were more concerned with the preservation of civil order in nearby Rangoon. For the international community the cyclone was a humanitarian crisis, but for the generals it was only a potential security one.

In the jungle capital of Naypyidaw, the junta may represent the last truly centralized regime in Burma’s post-colonial history. Whether through a peaceful, well-managed transition or through a tumultuous or even anarchic one, the Karens and Shans in the east and the Chins and Arakanese in the west will likely see their power increased in a post-junta, democratic Burma. That means the various pipeline agreements may have to be negotiated or renegotiated, at least to some degree, with the ethnic peoples living in the territories through which the pipelines would pass. The struggle over the Indian Ocean, or at least the eastern part of it near the top of the Bay of Bengal, may come down to who deals more adroitly with the Burmese hill tribes.

*

By appointing special envoys for Israel-Palestine, Afghanistan-Pakistan, and North Korea, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has been freed up to concentrate on the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific regions. Structurally, the State Department is now better organized than in decades for adjusting to a rising China and India.

*

“Burmese” signifies a nationality, “Burman” an ethnicity.

*

For example, the Ahoms, a Shan people, migrated down the Brahmaputra and clashed with the Mughals in the early seventeenth century.

*

In Brigadier Bernard Fergusson’s memoir of World War II in Burma,

The Wild Green Earth

(London: Collins, 1946), he writes (p. 133): “I can do no more than commend that gallant race [of Kachins] to my countrymen, who are mostly unaware of its heroics and unsupported war against the Japs. To carry on their own, independent way of life, they will need our protection … like that other splendid race the Karens.” This was typical of the favorable British attitude toward the hill tribes.

INDONESIA’S TROPICAL ISLAM

I

n early 2005, I was embedded on a United States Navy destroyer conducting relief work in the aftermath of the December 26, 2004, Indian Ocean tsunami, when the waters off Banda Aceh on the northern tip of Sumatra jutting out into the Bay of Bengal were, in one officer’s words, like a “floating cemetery.” Shoes, clothes, and parts of houses were in the sea; “it was like whole lives were passing by.” The tsunami marked the first time that these officers and sailors had seen dead bodies. In the spring of 2003 some of them had fired Tomahawks into Iraq from another destroyer, and then run over to a television to learn from CNN what they had hit. For them Iraq had been an abstraction. But going ashore by helicopter at Banda Aceh they had observed trees, bridges, and houses laid down in an inland direction, as if by high-pressure firehoses. It was a natural disaster, not a war, that had matured these young men and women in uniform.

1

Whereas the former Special Forces officers I met on the Thai-Burmese border represented the unconventional side of American power projection and relief assistance in the Bay of Bengal, these officers and sailors represented the conventional end of the spectrum. Yet as we shall see, the influence of the United States is limited when set against the vast, deep, and complex array of environmental, religious, and social forces impacting this region.

The earthquake that measured 9.3 on the Richter scale caused a tsunami that traveled at nearly 200 miles per hour at a height of more than 60 feet. It killed close to 250,000 people in Indian Ocean littoral

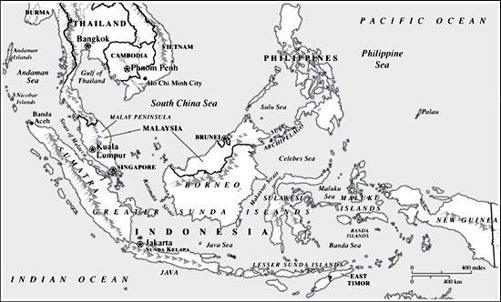

countries: perhaps comparable to the number of people who have died violently in Iraq since the U.S. invasion. The tsunami, which destroyed 126,000 houses in northern Sumatra alone, brought about damage over a radius of thousands of miles in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Burma, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, India, the Maldives, the Seychelles, Madagascar, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, and other nations. Its impact was a demonstration of the fragility of our planet and the natural forces that may be poised to reshape history.

Four years later I returned to the epicenter of this destruction, to an unreal landscape in Banda Aceh of mass graves holding tens of thousands of bodies under mute, empty fields; brand-new mosques, asphalt roads, and little iron-roofed housing communities; and wholly intact ships still stranded far inland where the great wave had deposited them. More than three miles from the beach, in the midst of a field with roosters running through the tall grass, improbably stands the

Ltd. Bapung

, a 2600-ton ship once used for generating 10.5 megawatts of electricity. It is over 200 feet long with a rusted red hull towering 60 feet, atop which is the much taller superstructure and filthy smokestack—like a massive industrial age factory. Close by, almost as an afterthought, is a 70-foot-long fishing boat resting on the roofs of two houses, where it came to settle.

I saw a mosque with buckled pillars—as if a mighty Samson had stood in their midst and pushed them apart—that had somehow survived. Another miracle was the waters that had swept up to the steps of the palatial Grand Mosque itself, only to recede. This is more than local lore. Photos show the truth of these events. The tsunami, like the great natural occurrences of the Bible, has had deep religious—and, therefore, political—significance in the region. The tsunami has clarified northern Sumatra’s historically unique and contentious relationship with Indonesia’s central government located on the main island of Java, even as it has, more significantly, affected the extraordinarily complex struggle for the soul of Islam itself in Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, and the fourth most populous country in the world.

The future of Islam will be strongly determined by what happens in Indonesia, where Middle Eastern forces from puritanical Saudi Wahabi groups to fashionably global Al Jazeera television compete for people’s hearts and minds against local forest deities and the remnants of polytheism. Nothing impacts religions as much as incomprehensible and

destructive natural events. Indeed, religion came about as a reaction to the world of nature. All of Indonesia’s 240 million people live inside a ring of fire: amid continental fault lines, shifting tectonic plates, massive deforestation, and active volcanoes. Half the people in the world who live within seven miles of an active volcano live in Indonesia. “After the tsunami, Islam here became more self-conscious, more self-aware almost,” observed Ria Fitri, a women’s activist and law professor.

The tsunami was not the first time in Indonesia’s modern history when an environmental event changed the course of religion and politics. As the author Simon Winchester documents, the eruption of Krakatoa in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra in 1883, followed by a tsunami, killed many tens of thousands of people; and in its socially devastating aftermath caused outbreaks of anti-Western Muslim militancy on Java that set a pattern for the century to come.

2

It is not merely fundamentalism per se that is the danger, but as with the case of Bangladesh, the way in which fundamentalism will interact with both the environment and demographic stresses.

During much of its history the region of Aceh in northern Sumatra was an independent sultanate with closer ties to Malaysia and—because of the sure and steady monsoon winds—to the Middle East than to the rest of archipelagic Indonesia. Aceh’s many mosques, and its organic relationship—because of the pepper trade and religious pilgrims—to the Arabian Peninsula gave the region the sobriquet “the Verandah of Mecca.” Aceh is the only part of Indonesia under Sharia law, yet beer is served in hotels, corporal punishment is limited to soft canings, and there are no forced amputations as in Saudi Arabia. Boys and girls play together in school yards, and women with bewitching smiles wear headscarves

(jilbabs)

but also tight jeans and high heels, and drive motorcycles. Elsewhere in Indonesia it is common to see women, with their hair completely covered, dress in tight blouses and skin-tight hot pants, marked with the latest designer clothes. It is said, though I could not verify it, that there are actually women in Jakarta who wear both

jilbabs

and tank tops with exposed bellies. In Indonesia, modesty stops at the neck.

Yet the helmet-shaped

jilbab

is a mark of modernity, for it indicates that a woman has learned about religion through schooling. Wearing it allows a woman, now armored with symbolic modesty, to enter the

professional world of men. “There are few clear-cut lines for women’s dress codes, as long as the body is covered. Much is open to personal interpretation,” explained Ria Fitri, the women’s activist. “The stricter dress codes of some parts of the Middle East and Malaysia are simply not practical here.” In a larger sense, women’s dress codes in Indonesia are much less a sign of hypocrisy than of wondrous religious diversity, since Islam, even in highly observant Aceh, is enmeshed in a peaceful yet momentous struggle with underlayers of Hinduism and Buddhism that persist to this day.

With well over 200 million of its 240 million inhabitants Muslim, Indonesia represents one of Islam’s greatest proselytizing success stories.

3

This is particularly remarkable because Islam came to Indonesia not through military conquest as it did almost everywhere else, from Iberia to the Indian Subcontinent, but, starting in Aceh in the Middle Ages, through seaborne Indian Ocean commerce. In many cases the bearers of Islam were merchants, and thus people with a cosmopolitan outlook who did not seek homogeneity or the destruction of other cultures and religions. The earliest Muslim missionaries in Java are known as the nine saints (Wali Sanga). This myth is similar to that of the twelve Sufi saints

(auliyas)

who brought Islam to Chittagong in Bangladesh. It is quite possible that these saints in the non-Arab eastern reaches of the Indian Ocean were traders.

The places where Islam established early and deep roots were those closest to international trade routes, such as the Malay Peninsula and here on the Sumatran shores of the Strait of Malacca.

4

The farther inland you go, into darkly mauve mountains dripping with greenery, the more idiosyncratic Islam becomes. Rather than being swiftly imposed by imperial armies of the sword, Islam seeped gradually into Indonesia over the course of hundreds of years of business and cultural interchanges, replete with paganistic Sufi influences. Many of the Muslims who came here from the Greater Middle East—Persians, Gujaratis, Hadhramautis—were themselves victims of oppression, and thus open-minded in a doctrinal sense, explained Yusni Saby, the rector of the State Institute of Islamic Studies in Banda Aceh.

“In Indonesia,” writes the late and esteemed anthropologist Clifford Geertz, “Islam did not construct a civilization, it appropriated one.” That is, Islam became merely the top layer of a richly intricate culture. Whereas Islam, as Geertz explains, when it swept through Arabia and North Africa, moved into “an essentially virgin area, so far as high

culture was concerned,” in Indonesia, beginning in the thirteenth century, Islam encountered “one of Asia’s greatest political, aesthetic, religious, and social creations, the Hindu-Buddhist Javanese state.” Even after Islam had spread throughout Indonesia, from the northern tip of Sumatra in Aceh to the easternmost Spice Islands almost three thousand miles away, the Indic tradition, though “stripped … of the bulk of its ritual expression,” was left intact with its “inward temper.” With few exceptions, Geertz goes on, the Indic-Malay “substratum” of “local spirits, domestic rituals, and familiar charms” continued to dominate the lives of the mass of the peasantry. Though Islam as an accepted faith was encountered everywhere in Indonesia by the end of the nineteenth century, as a “body of … observed canonical doctrine it was not.” Thus, Geertz describes Indonesian Islam as “malleable, tentative, syncretistic,… multivoiced,” and “Fabian in spirit.”

5

Today no more than a third of Muslim Indonesians are orthodox

(santri);

the rest are syncretic

(abangan).

6

Therefore, Indonesian Islam represents the sum of South and Southeast Asia’s nuanced response to Islamic identity, an ideal that has eluded much of the Arab world.

*