Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (48 page)

Read Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power Online

Authors: Robert D. Kaplan

Tags: #Geopolitics

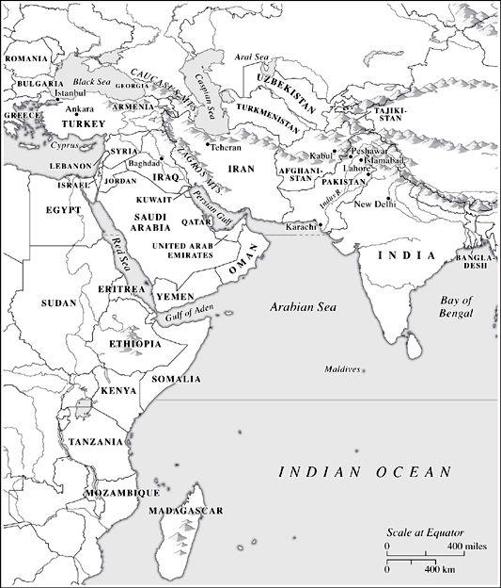

Here it is worthwhile revisiting the era of great Chinese sea power in the Indian Ocean during the Song and early Ming dynasties, from the late tenth to the early fifteenth century, which culminated in the celebrated voyages of the eunuch admiral Zheng He. These expeditions saw Chinese commercial and political influence extend as far away as East Africa, and featured Chinese landings in such places as Bengal, Ceylon, Hormuz, and Mogadishu. In particular, Zheng He’s voyages from 1405 to 1433, which encompassed hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of men, were not merely an extravagant oddity designed to show the Chinese flag in South Asian and Middle Eastern harbors. They were also designed to safeguard the flow of vital goods against pirates, and were in other ways, too, a demonstration of soft, benevolent power. Interestingly, the Chinese navy of the Song and early Ming eras did not seek to establish bases or maintain permanent presences in Indian Ocean ports the way the European

powers did later; rather, they sought access through the building of alliances in the form of a tribute system.

10

This more subtle display of power seems to be exactly what the Chinese intend for the future. Take Pakistan as a model: the Chinese have maintained a security and trade relationship with Pakistan, constructing the Karakoram Highway that connects Pakistan with China, as well as a deepwater port at Gwadar on the Arabian Sea. This helps develop the access China desires, even as the Gwadar harbor itself will be run by the Singaporeans. Indeed, full-fledged Chinese naval bases in places like Gwadar and Hambantota would be so provocative to the Indians that it is frankly hard to foresee such an eventuality. “Access” is the key word, not “bases.”

The Ming emperors eventually ended their forays into the Indian Ocean, but this happened only after they were pressured by the Mongols on land and thus had to turn their attention to China’s northern border. No such difficulties threaten China now. To the contrary, China is making significant progress in stabilizing its land frontiers and has even demographically laid claim to parts of Russian Siberia with Chinese migrants. Thus, the way is clear for China to turn its attention to the sea.

Nevertheless, it is worth keeping in mind that we are talking here of only a likely future. For the present, Chinese officials are focused on Taiwan and the First Island Chain, with the Indian Ocean a comparatively secondary concern. Thus, in the years and decades hence, the Indian Ocean, in addition to everything else, will register the degree to which China becomes a great military power, following in the footsteps of the Portuguese, Dutch, and others. What is China’s grand strategy? The Indian Ocean will help show us.

Imagine hence, a Chinese merchant fleet and navy present in some form from the coast of Africa all the way around the two oceans to the Korean Peninsula, covering, in effect, all Asian waters within the temperate and tropical zones, and thus protecting Chinese economic interests and the maritime system within which those interests operate. Imagine, too, India, South Korea, and Japan all adding submarines and other warships to patrol this Afro-Indo-Pacific region. Finally, imagine a United States that is still a hegemon of sorts, still maintaining the world’s largest navy and coast guard, but with a smaller difference between it and other world-class navies. That is the world we are likely headed toward.

To be sure, the United States will recover from the greatest crisis in

capitalism since the Great Depression, but the gap between it and Asian giants China and India will shrink gradually, and that will affect the size of navies. Of course, American economic and military decline is not a fatalistic

given

. No one can know the future, and decline, as a concept, is overrated. The British Royal Navy began its relative decline in the 1890s, even as Great Britain went on to help save the West in two world wars over the next half century.

11

Still, a certain pattern has emerged. The United States dominated the world’s economy for the Cold War decades. After all, while the other great powers had suffered major infrastructure damage in their homelands in World War II, the U.S. came out of that war unscathed, and thus with a great development advantage. (China, Japan, and Europe were decimated in the 1930s and 1940s, while India was still under colonial rule.) But that world is long gone, the other nations have caught up, and the remaining question is how does the U.S. respond responsibly to a multi-polarity that probably will become more of a feature of the world system in years to come.

Naval power will be as accurate an indicator of an increasingly complex global power arrangement as anything else. Indeed, China’s naval rise can present the U.S. with great opportunities. Once more, it is fortunate that the Chinese navy is rising in a legitimate manner, to protect economic and rightful security interests as America’s has done, rather than to forge a potentially suicidal insurgency force at sea, as Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy appears bent on doing in the Persian Gulf.

12

This provides China and the U.S. with several intersection points of cooperation. Piracy, terrorism, and natural disasters are all problem areas where the two navies can work together, because in these fields China’s interests are not dissimilar to America’s. Moreover, China may be cagily open to cooperation with the U.S. on the naval aspects of energy issues: jointly patrolling sea lines of communication, that is. Both China and the U.S. will continue to be dependent on hydrocarbons from the Greater Middle East—China especially so in coming years—so the interests of the two nations in this sphere seem to be converging. Therefore, it is not inevitable that two great powers that harbor no territorial disputes, that both require imported energy in large amounts, that inhabit opposite sides of the globe, and whose philosophical systems of governance, while wide apart, are still not as distant as were those between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, will become adversaries.

Thus, leveraging allies like India and Japan against China is responsible in one sense only: it helps provide a mechanism for the U.S. to gradually and elegantly cede great power responsibilities to like-minded others as their own capacities rise, as part of a studied retreat from a unipolar world. But to follow such a strategy in isolation risks unduly and unnecessarily alienating China. Thus, leveraging allies must be part of a wider military strategy that seeks to draw in China as part of an Asia-centric alliance system, in which militaries cooperate on a multitude of issues.

Indeed, “Where the old ‘Maritime Strategy’ focused on sea control,” Admiral Michael Mullen, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said in 2006 (when he was chief of naval operations), “the new one must recognize that the economic tide of all nations rises not when the seas are controlled by one [nation], but rather when they are made safe and free for all.”

Admiral Mullen went on: “I’m after that proverbial 1,000-ship Navy—a fleet-in-being, if you will, comprised of all freedom-loving nations, standing watch over the seas, standing watch over each other.”

As grandiose and platitudinous as Admiral Mullen’s words may sound, it is in fact a realistic response to America’s own diminished resources. The U.S. will be less and less able to go it alone and so will rely increasingly on coalitions, for national navies tend to cooperate better than national armies, partly because sailors are united by a kind of fellowship of the sea, born of their shared experience facing violent natural forces. Just as a subtle Cold War of the seas is possible between the American and Chinese navies, conversely, the very tendency of navies to cooperate better than armies may also mean that the two navies can be the leading edge of cooperation between the two powers, working toward the establishment of a stable and prosperous multi-polar system. Given America’s civilizational tensions with radical Islam, and its at times quarrelsome relationship with Europe, as well as with a bitter and truculent Russia, the United States must do all that it can to find commonality with China. It cannot take on the whole world by itself.

The United States must eventually see its military not primarily as a land-based meddler, caught up in internal Islamic conflict, but as a naval- and air-centric balancer, lurking close by, ready to intervene in tsunami- and Bangladesh-type humanitarian emergencies, and working in concert with

both the Chinese and Indian navies as part of a Eurasian maritime system. This will improve America’s image in the former third world. While America must always be ready for war, it must work daily to keep the peace: indispensability, not dominance, should be its goal. Such a strategy will mitigate the possible dangers of China’s rise. Even in elegant decline, this is a time of unprecedented opportunity for Washington, which must be seen in Monsoon Asia as the benevolent outside power.

Western penetration of the Indian and western Pacific oceans began bloodily with the Portuguese at the end of the fifteenth century. The supplanting of the Portuguese by the Dutch, and the Dutch by the English, came also with its fair share of blood.

*

Then there was the supplanting of the English by the Americans in the high seas of Asia, which came via the bloodshed of World War II. Therefore, a peaceful transition away from American unipolarity at sea toward an American-Indian-Chinese condominium of sorts would be the first of its kind. Rather than an abdication of responsibility, such a transition would leave the Greater Indian Ocean in the free and accountable hands of indigenous Asian nations for the first time in five hundred years. The shores of the twenty-first century’s most important body of water lack a superpower, and that is, in the final analysis, the central fact of its geography. China’s two-ocean strategy, should it ever be realized, will not occur in a vacuum, but will be constrained by the navies of other nations, and that will make all the difference.

*

My thinking about this maritime world depends substantially on a group of scholars at the U.S. Naval War College whose work on China’s maritime strategy has been exhaustive, creative, and very moderate in tone. They are Gabriel B. Collins, Andrew S. Erickson, Lyle J. Goldstein, James R. Holmes, William S. Murray, and Toshi Yoshihara. In particular, I am heavily indebted to four publications for statistics and many insights: James R. Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara,

Chinese Naval Strategy in the 21st Century: The Turn to Mahan

(New York: Routledge, 2008); Toshi Yoshihara and James Holmes, “Command of the Sea with Chinese Characteristics,”

Orbis

, Fall 2005; Gabriel B. Collins et al., eds.,

China’s Energy Strategy: The Impact on Beijing’s Maritime Policies

(Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008); and Andrew Erickson and Gabe Collins, “Beijing’s Energy Security Strategy: The Significance of a Chinese State-Owned Tanker Fleet,”

Orbis

, Fall 2007.

*

One should not forget the French, whose role, particularly in the islands of the southwestern Indian Ocean, is covered expertly by Richard Hall in

Empires of the Monsoon: A History of the Indian Ocean and Its Invaders

(London: HarperCollins, 1996).

UNITY AND ANARCHY

C

hina is renewing its historical links with Arab and Persian civilizations, and as India never really severed them, the Indian Ocean world—the universal joint of the Eastern Hemisphere—is hurtling toward unity. “The rise of China’s economy is an accelerant for the Arab world,” writes Ben Simpfendorfer, chief China economist at the Royal Bank of Scotland. “Its demand for oil has helped fuel the Arab economies. Its factories churn out consumer goods to fill Dubai’s and Riyadh’s air-conditioned malls.”

1

For the Arabs, the rise of China offers an alternative strategic partner to the West. Before the tide turned in the Allies’ favor in World War II, strategists such as Nicholas Spykman concerned themselves with Africa and Eurasia achieving unity through the domination of fascist powers.

2

That unity may be upon us in coming years and decades, not through military domination, but through the resurrection of a trading system, like that established by the medieval Muslims, and perpetuated by the Portuguese.

And in this increasingly taut web of economic activity, Africa, at the Indian Ocean’s western extremity, is not being left out. Africa’s renewal, however slow and fitful, is being impelled in large measure by investment from the Middle East and Asia. The third world, as it used to be known, is disappearing gradually, as the parts of it that have developed are now concentrating their energies on building up those that have not.

Indeed, globalization is not merely a phenomenon happening between the so-called West and the rest, but between the rest itself. Thus, Africa is becoming the beneficiary of a resurgent China and also of an

India that is becoming ever more dynamic, as it rises above the confines of Hindu nationalism and Islamic extremism.