Mornings With Barney (10 page)

Read Mornings With Barney Online

Authors: Dick Wolfsie

Again, my career flashed before me along with the headlines of the next day: BARNEY POISONED. ANTS MOVE BACK UNDER FRIDGE.

I wrestled him into the car and raced to a local twenty-four-hour pet emergency clinic just a few minutes away. It was 3 in the morning and I began ringing the bell, then banging on the door. The on-call veterinarian, who had been sleeping prior to my interruption, hastened to the entrance. She peeked through the peephole in the door. Unfortunately, she recognized me.

“What is it, Mr. Wolfsie? Is Barney okay?”

“He ate an ant trap. Is he going to die?” I watched her expression. She didn't seem to be taking my extreme angst very seriously.

“Heavens no,” said the vet. “Those things don't even kill ants.”

I once composed a list of the ten most interesting things he ever ate. None of these things ever caused any distress. Except in me. This is not to say that there wasn't evidence wafting in the air that he had been naughty, but there was just as much proof he had remained healthy despite some very unorthodox ingestions.

The Top Ten Things He Ate

1

- Four sticks of butter at one time

- An entire bucket of KFC I left on my backseat (remember)

- Half a turkey on Thanksgiving Day

- An entire platter of lasagna (Garfield, eat your heart out)

- Two packages of hot dog buns

- A head of lettuce

- Two cherry pies

- A box of chocolate cherries (I know he's not supposed to eat chocolate. But he didn't know that)

- That $25 giant pepperoni pizza, including the box

- An entire loaf of Italian bread (Well, not the whole loaf. He buried the rest under the blankets at the foot of Brett's bed.)

A final note of pride: Emergency veterinarians tell me it is not uncommon for beagles to enjoy batteries, dental floss, and sweat socks, each of which requires invasive surgery to save the animal. Barney generally restricted his diet to human food, the ant trap being a notable exception.

Oh, and by the way, it's hydrogen peroxide. One teaspoon of 3 percent hydrogen peroxide (make sure the strength is not any higher than 3 percent) per each ten pounds of body weight. Just in case you find a beagle. Or a beagle finds you.

Barney was more than a TV hound.

He was a multimedia megastar who found his way into just about every medium there was.

He appeared on the cover of the city magazine

Indianapolis Monthly

three times. Give me a second here while I figure out how many times I was on the cover.... Okay, never.

In one edition, the publishers wanted to highlight the major symbols of the Circle City, Indianapolis. They put only three icons on the cover: A basketball, a race car, and a photo of Barney. Talk about being in good company!

Barney was also a Hollywood movie star. Not Hollywood, California, but the Hollywood Bar and Filmworks in downtown Indy. It has since moved to Chicago, but in its day it was the yuppie place to go in town, the one theater where you could see a movie and sip Merlot at the same time.

The owner, Ted Baltuch, like any smart hotel owner, knew that seats with no people in them, like rooms with no guests, did little for the bottom line, so to speak. As a result, he gave away free tickets to Saturday and Sunday kids' matinee movies. The hope was that burger-and-fries sales would cover his expenses and introduce the theater to the children's parentsâwho might then return without kids.

For several years, I would mention the freebie on the morning show, as well as the additional incentive of meeting Barney and me before the movie. Kids could pet Barney and get autographed photos of the two of us. With the help of a good flick (

Toy Story

, for example), it was not uncommon to sign two hundred pictures during the hour preceding the show. Ted paid me for my appearance, and Barney was bellyrubbed for sixty minutes. I think he got the better deal.

Ted knew that the parentsâthe ones who watched the newsâwere usually more interested in the trip to meet Barney for the celebrity angle than the kids, many of whom just loved dogs in general. But I did notice as time went on that more and more children were watching our news, in part motivated by their chance to see Barney.

Success in television requires a constant influx of viewers, a curious blend of keeping the old and attracting the young, although for the past few years, keeping the older viewer has lessened in priority. Of course, TV stations now sell a lot of Viagra ad slots, suggesting not all TV fans are twenty-somethings.

The news executives at WISH-TV later felt that a dog on the news skewed toward older viewers. But ironically, many of those youngsters who had encounters with Barney are now young adults with their own families. “I grew up watching you and Barney!” a young woman will tell me with her two toddlers at her side. Sometimes I can't believe I have spanned an entire generation on TV. At this point I have kept my face on TV in Indy for about a century. At least in dog years.

Ted had another idea: how about if Barney and I appeared in a short piece of film that would welcome guests to the theater? The clip would explain some of the required information for the movie guests: Smoking rules, NO TALKING, fire exits, NO TALKING, bathroom locations, NO TALKING.

Shooting the spot required that I recite those basic theater rules on camera. Throughout my television and radio career I have been blessed with the gift of ad-lib, but God did curse me with zero capacity to remember prewritten lines. While I struggled with the script, I sat there with a bag of buttered popcorn as a prop, which drove Barney insane. Just when I was about to do Take No. 42, Barney would bury his nose in the popcorn, scattering the kernels all over the table. I'd forget my lines and the director would yell, “Cut! Take 43.”

Well, how dense was I? Barney had found the perfect vehicle to inject humor into this otherwise rather vanilla presentation. Okay, now this

was

my idea. To ensure his total obsession with the popcorn, I added a chicken wing to the bottom of the box and situated the treat right under his nose.

Take 44: I still stumbled with my wording, but that was okay because I had clearly been distracted by the popcorn pooch. “Leave my popcorn alone,” I continually admonished him, but to no avail. In the video, his entire head is buried in the popcorn box. All you see are ears flopping over the box.

The more Barney tried to exhume that hidden chicken wing, the funnier it got. Take 45 completed the shoot. I liked working with a pro. That movie introduction ran thousands of times over the years. Whenever I would visit the theater, I'd enjoy it as people laughed at the movie opening.

Barney's success on the big screen led to more success for him on the little screen, which was based on what Channel 8 was showing on the big screen. I'd better explain.

General Manager Paul Karpowicz's feelings about Barney grew more positive over the years, so much so that he began to think about additional ways to capitalize on the dog's popularity.

WISH-TV had a stockpile of old movies, films that had been purchased but were just taking up space in the studio basement. Others were part of an old rental agreement that we were contractually stuck with. Some were good, but many clearly were in the B-movie category. What did the B stand for? “Maybe it stands for beagle,” surmised Karpowicz, who suggested to me one day that we do a late-night show calledâare you ready for this?â

Barney's Bad Movies.

A gutsy move, really. We were advertising that the movies were stinko, but by putting Barney's name on the program, it might attract a bit more attention in that late-night slot where ratings had waned on the weekends.

But wait. It was more than just the title for a show. We built this elaborate set with movie lights, an old movie projector, and a doghouse. And a fire hydrant that I borrowed from the city. There was a desk for me and a chair for the hound. This was real showbiz. No expense was spared. That's because we had no money. We built the set from stuff people brought in. Kim Gratz, one of the producers, was assigned the project. She had no idea how this was going to work. And that was twice as much as I knew.

We decided that Barney should have an actual role in rating the weekly movies. For each film, we would prerecord what is called a wrap-around (TV talk for an intro and “outro” to the movie). Usually we'd make fun of the movie, but we'd always feature Barney in some quirky, offbeat way. If the movie was really bad, we'd take shots of Barney sleeping, usually on his back, and put them in the corner of the screen during the picture. Then when it was over we'd rate the movie withâyeah, you guessed itâone to four fire hydrants. Okay, so you didn't guess it.

Barney jumped on the couch and really did sleep through every movie, not unlike our viewers, I'm quite sure. The ratings did not rise appreciably, but Karpowicz's contention wasâquite clever, reallyâthat even if people didn't watch the flick, they'd see the promos and word would spread about this off-the-wall idea. People would talk about WISH-TV. And maybe that would boost ratings in the morning.

Over the five-year run we even had special guests like Indianapolis Mayor Steve Goldsmith, Michael Medved (the film critic), Boomer (the Pacers mascot), Soupy Sales, and many of the Channel 8 reporters. Patty Spitler, the station film critic, made several appearances, often to defend the movie and spar with Barney over his fire hydrant ratings. Patty was much more forgiving. Barney was a tough critic, but even-pawed. He slept through everything.

Well, not everything. During one commercial break he realized it was a real fire hydrant on the set and he reacted appropriately, especially considering the quality of the movie.

One Friday night we showed

Patton

, starring George C. Scott. This was a far better movie than our usual fare, so to celebrate, I dressed as a WWII general and we even found a K-9 Army uniform for Barney. Sadly, he only got to be a corporal, one of the few times I outranked him. At the breaks, I barked orders to Barney to

sit, stay, come

. I don't think he would have listened to the real Patton, either.

Barney's Bad Movies

ran almost four years, but after Karpowicz left, the new boss didn't have quite the same commitment to the idea, it not being his and all. Barney finally lost his gig, the victim of poor ratings and the end of our film rights to many of the flops.

That's showbiz, even if you're a dog.

TV, movies, magazines. What about radio? Even the growing popularity of Barney could not buffer me from what was almost a career and personal disaster in 1994, a year that threatened my relationship with my son, my wife, and the potential for a growing fan base. There were times when I thought that Barney was my only friend.

I was content with my job at WISH

but recognized that I was still basically a talk show host at heart. Morning pieces were two minutes long but embarrassingly short in content. Sure, I did some innovative things, stuff that most others would not have dared do on live TV, but the segments were basically sound bitesânothing more than a snapshot of an issue or upcoming event. It was a break from what was often a typical morning newscast, chock-full of natural disasters, murders, and stock traffic reports. The morning team at WISH was clearly the loosest and most informal of all the anchors on the different stations, but news was basically serious.

I often thought back to my previous stints when I'd been interviewing politicians, doctors, and lawyers; people with dramatic personal stories who might have spent an hour on the couch next to me. The show was often about just one issue. It was educational. I enjoyed that role. It lit up the teacher in me.

My role at WISH was a blast. I did love getting laughs and creating on-the-spot lunacy each morning, but there was something missing. I didn't want my career to end sitting on a circus elephant or interviewing a pastry chef.

In November 1994, I returned a call from the local mega AM station, WIBC. They were looking for a few local personalities to fill in the 9-to-12 lineup while they searched for a new host for that spot. Their list of syndicated talkers included Rush Limbaugh from 1 to 4, and while Rush was not quite the 800-pound gorilla he is now, his girth had started spreading through the talk show world by the mid-nineties.

Indiana is a conservative state. Despite having a Democratic governor at the time, Hoosiers had seldom voted for a Democrat for president. The last time was in 1966, when LBJ got the nod, ironic in this story because Johnson had been in the news that year, accused of improperly handling his beagle pups by holding them by their ears and dangling them in front of the camera. Had he done that during the election of 2004, even Indiana wouldn't have voted for him.

I doubt the general manager at WIBC saw me as a potential permanent replacement for the present host. Stan Solomon had been in that slot and was going to move to afternoon drive time. Solomon was a right-winger, always railing about Bill Clinton, convinced he murdered Vince Foster and that Hillary was femi-Nazi-lesbo. Okay, this is an exaggeration, but Solomon did attract a definite audience, just not the kind I aspired to achieve or had any chance of pleasing.

I filled in for three mornings, a total of nine hours on airâtimewise the equivalent of an entire month on TV during my morning segments. It was a heady experience, but I kept the volume of the discourse turned down low. I talked about mundane issues, but I got a clear smattering of what the job would mean when one morning I expressed my opposition to corporal punishment. Listeners called, demanded I be fired, even spanked, convinced WIBC had hired a bleeding-heart liberal. Fire me? I hadn't even been hired.

Yes, I was a liberal, one of the few in Indiana, who had been given access to the airwaves. The responsibility scared the hell out of me. But it also turned me on.

Oh, please,

I thought,

don't ask me to do this full time. I won't be able to say no.

Other hosts filled in the next two weeks and when I didn't hear anything for more than a month, I resigned myself to the fact that I was not right (far-right enough) for the job. I felt then, as I do now, that it is tough to offer a nuanced view of the world on the radio, which, in my opinion, is what happens when you espouse a more liberal approach to issues. But it just doesn't work. Most people need black and white, good and evil. They need something to get in a sweat about. As Garrison Keillor once noted, “Unitarian ministers don't do much preaching in the subway.”

I later learned that that management had liked the reaction I had initially garnered. No one had ever disagreed with Rush. The phones had lit up. Most people didn't like what I had to say, although many did think my manner and approach were evenhanded. I was offered the job after all, with the understanding that I would present an alternative view to the right-leaning hosts presently on the air, which now included two other talkers whose shows aired in the later afternoon and evening. I was flattered by the opportunity; I didn't weigh the downside.

Mary Ellen was good at weighing. She was afraid that my decision had the potential to endanger my growing popularity at the TV station. She knew I had a penchant for looking for good issue-oriented scraps at cocktail parties, but this would take my argumentative nature to a new level. And she said it would change my brand, no doubt a concept from one of her advertising textbooks ...

“What does that mean, âchange my brand,' Mary Ellen?”

“It means that people think they're about to take a swig of orange juice and you surprise them with grapefruit. It's jarring.”

Damn, Mark Twain was right. There

is

nothing more annoying than a good example.

True, the idea of broadcasting my radical (in New York, we say enlightened) views on a 50,000-watt station throughout central Indiana did pose a risk. Maybe it did jeopardize my brand, but I was feeling my Wheaties.

My boss at WISH, Lee Giles, the news director, had heard me on the radio during the tryouts and was impressed, but his enthusiasm was tempered by concern. I was a funny guy, the reporter doing the light, fluffy stuff. And everybody enjoyed watching me (and, let's be honest, Barney), so why would I go and ruin this by actually showing people I had opinions on controversial issues? To me, it seemed as if they were afraid I'd reveal that I had a brain. Giles didn't word it that way, but that was the feeling I got.

Nevertheless, I convinced myself I had an obligation to do this: to literally broadcast a more progressive viewpoint over a radio station that was decidedly conservative. I was consumed with this feeling of self-importance. Not a flattering quality.

I took the job.

The new routine was grueling. Up at 3:30 in the morning to do my segments for Channel 8, then on to the WIBC studios by 9 AM on the north side of town to host three hours of political discourse, peppered by angry viewers who now had a good reason not to like meâdespite the dog. In fact, it was not uncommon for viewers to observe that “Barney has more brains than you do.”

My wife's mother, who I swear had the hots for Bill O'Reilly, considered my liberal views shameful and often denied I was her son-in-law at the retirement home bridge parties. That hurt. I wondered whether she had rewritten her will.

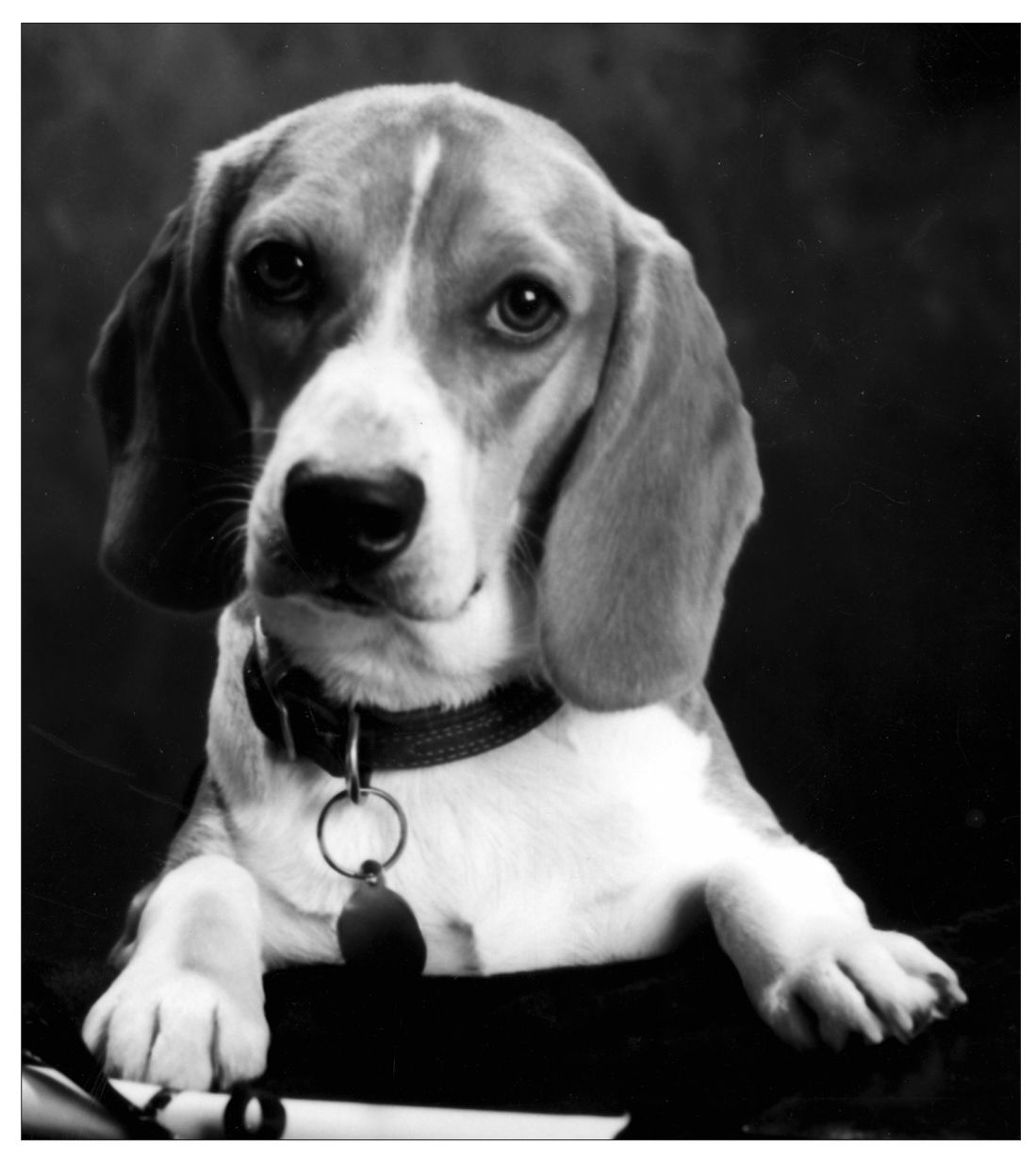

The classic Barney photo by Ed Bowers. We printed 5,000 of them and signed each one to fans: Your pals, Dick and Barney.

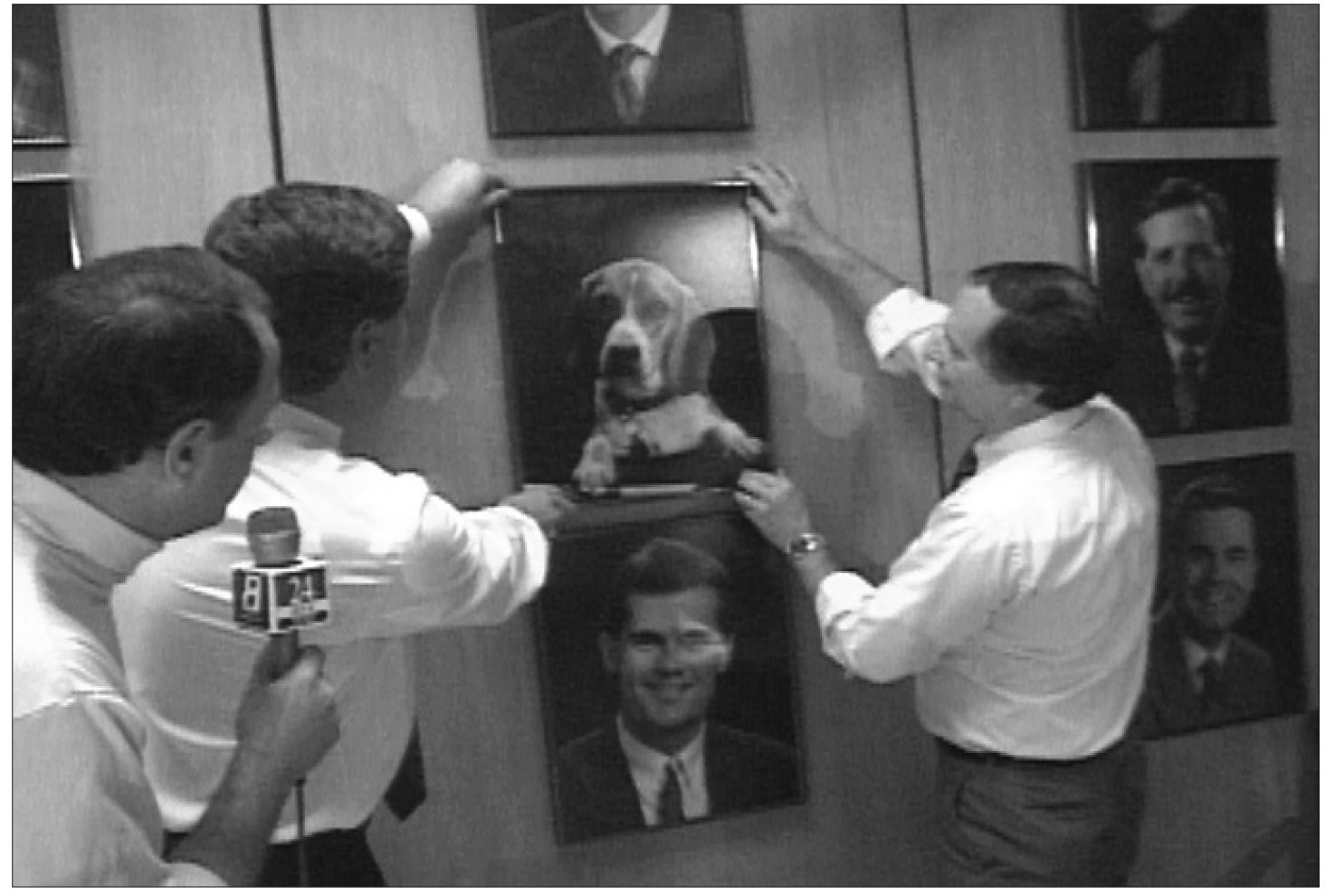

Executives substitute Barney's photo for the morning anchor's on WISH-TV's wall of fame.

At a local hotel. Barney gave it four starsâmostly for the room service.

The sign might have said “NO PETS” but Barney was a fan of NO RULES. He was at home everywhere.

At the Fair. If it moved, he chased it. If it didn't, he ate it.

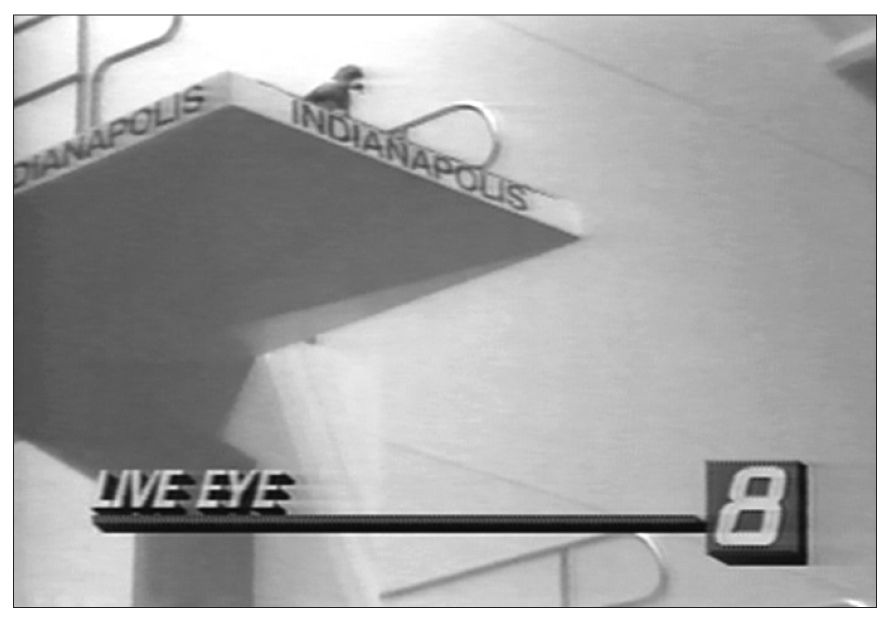

On top of a diving platform at the local natatorium. He didn't jump, but all of Indiana held their breath.