Mornings With Barney (12 page)

Read Mornings With Barney Online

Authors: Dick Wolfsie

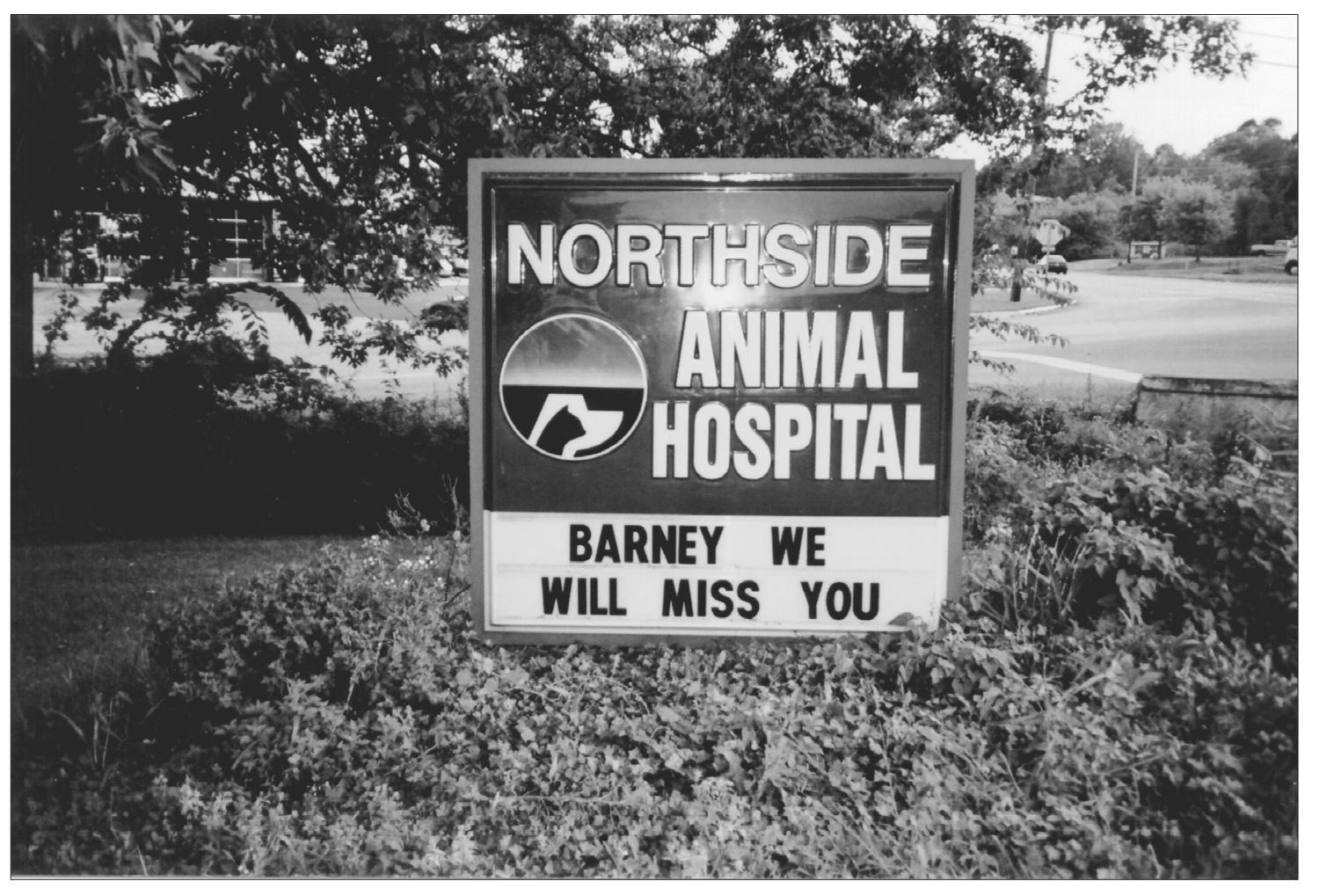

The doctors in this clinic never treated Barney. They just loved him like everyone else.

During all this, Barney remained my rock. Because he was with me during every morning TV segment, he also accompanied me to the radio station. We arrived each morning at about 8:30, just in time for me to review notes I had prepared at home and make a transition from my segment on TV baking chocolate éclairs or laser tag to three hours of ranting about abortion rights or gun control. There was no tougher segue in television.

In the radio studio, Barney had his own chair, actually more of a bar stool, that required some human assistance for him to negotiate. But once perched in place, he never moved the entire three hours, proof he had (1) great patience with my liberal lectures and (2) a healthy pair of kidneys.

One reason for Barney's patienceâhardly a beagle traitâwas that a procession of the radio staff filtered into the studio each morning, armed with a variety of dog treats. Barney sat there, unmoved (in more ways than one) by diatribes about the merits of universal health care or a harangue about prayer in school, but always with his radar set for the next person to enter the booth and slip him a nosh of pepperoni or a chocolate chip cookie.

His favorite provider was Sally, one of the veterans of the WIBC sales department who never missed a morning visit. At 10 AM Sharp, just before they ran the Rush Limbaugh promo, she'd slip into the studio with a biscuit. Soon, Barney actually connected the Limbaugh theme music with her arrival. The irony never escaped me. The music got us both riled up.

I savored every minute on the air, but it had a devastating impact on me physically and emotionally. Most feedback on the air was negative, complaints about my liberal views. I thought I handled things pretty well....

Caller: “I hate the government. They never do anything right. The less government, the better. We'd be better off if they would just shut down.”

“What do you do for a living, sir?” I asked.

“Nothing. I'm on Social Security.”

“How do you pay your medical bills?”

“I have Medicare. Oh, and I'm on disability.”

“Did you go to college?”

“Yeah, on the GI Bill.”

“How'd you buy your house?”

“I got an FHA loan. Say, listen, Wolfsie, what the heck does this have to do with how much I hate the government?”

The grueling part of the job was the preparation. Unlike one of the other radio hosts at the time who thought that the facts were just a distraction to his point of view, I read every newspaper and magazine. I watched every news show. I was obsessed with being totally prepared. It consumed my life, more so than the TV. I had so little time in the day to get everything done that I booked TV guests during commercial breaks on the radio.

In addition, I accepted a weekend job in New York, guesthosting a cable show, a precursor to shows like

The Factor

and

Hannity & Colmes.

Again, a job I should have turned down. Damn ego. Now I was on TV three hours each morning, then radio the next three. The rest of the weekdays my face was either buried in a newspaper or watching news shows. Then on Friday afternoon, I'd fly to New York to do the cable show.

Brett, who was then seven, saw little of me. To Mary Ellen, I was just a rumor. It was the best year of my life. It was also the worst.

Because I was on TV every morning and because Barney was always at my side, I was a moving target with a bull's-eye on my back. Why call into the radio show when you could accost Dick Wolfsie in the supermarket or the drugstore? All of a sudden, people weren't thanking me for telling them about the new bakery in town or showing them the new museum exhibit, they were carping about my defense of the ACLU.

I was once stopped by an angry listener in a parking lot who took great issue with my views on home schooling. I listened to the guy for about ten minutes. Maybe I was just having a bad day, but for some reason I realized what a toll this radio experience was having on me.

I climbed into the car, drove about three blocks, pulled over to the side of the road, and burst into tears. I hugged Barney so hard, he squealed.

My approach on the radio didn't sell. I refused to rant. I tried to be annoyingly reasonable. But was that what the station wanted? They hoped for controversy, but they were concerned when listeners called to complain about my views. On the other hand, they knew that a strong reaction to me might ultimately generate ratings. It was an odd calculus. I was caught in the middle. Nobody knew who they wanted me to be. Least of all me, although I was sure I would not compromise my views based on viewer feedback.

Here was the bottom line (and it was all about the bottom line): You can get away with a weak opening act for Wayne Newton in Vegas. On radio, it's too easy to switch to another channel. They were beginning to think that Rush deserved a better lead-in.

Quitting did not seem like an option. I had lost enough jobs in my life that I didn't feel I had the luxury of giving one up on my own. There was hope that eventually I'd get canned. It had certainly happened before. Too many times.

After I had been on the air for about six months, a new program manager took over, part of the sale of WIBC to Emmis Communications. His last name was Hatfield, a subtle hint I was in for a feud. I knew from my first exchange with him that I was doomed. He made me justify every issue I discussed, every guest I booked, and every position I took. He didn't like the way I read the weather or the way I introduced the commercial spots. He didn't like the fact I was also on TV. Oh, and he didn't like dogs in the studio. Hey, this all looked like a fairly good clue to some serious trouble down the road.

In January 1995, I had just finished my show when I was passed a note to see the program manager immediately. I walked into his office and it was clear what would ensue. I was going to get the ax. Seated next to Hatfield was the GM, who I had thought was a decent guy and had worked with before.

“That was your last show,” Hatfield said. “People don't like you. Give me your key.”

Huh? I looked at the GM, who knew of my growing popularity in the TV market. The guy just sat there. Not a word. I'm still ticked about that.

Barney, who had accompanied me as always, was in the chair next to me.

“Yes, you're fired,” repeated the program manager, “and so's your little dog, Barney.” The wicked witch of the Midwest had spoken.

The next day, the paper ran the story of my dismissal. Later in the week, scores of letters were printed, some in support of me, but most agreeing that my views just didn't jive with most Hoosiers. I had nothing to be ashamed of, but the public nature of the axing was humiliating.

I walked out of the studio and loaded Barney in the car. I remember tilting the seat back just to rest my brain, a clear indication to the beagle that he could nestle his head on my lap. This was common behavior when we went on speaking engagements that required a lengthy road trip and a nap along the way at a rest stop.

I have no romantic notions that dogs always sense what their owner is feeling. I only know this: With his face in my lap, he rolled his eyes toward the top of his head and fixed his gaze on me. When I finally returned the seat to the upright position, his head remained in my lap for the trip home.

For me, it was the end of daily hourlong debates about O. J. Simpson, Bosnia, and welfare mothers. For Barney, it was the end of 10 AM treats. We would both survive. We had a TV show to do the next morning.

Mary Ellen was relieved, and not surprised at the news. She thought Brett would benefit from the change. That night I decided to tell my son, couching it in a positive narrative. “Dad has some great news. You know how little time we have to spend together? Well, starting tomorrow, Dad has decided not to do the radio show anymore. I want to have more time for us to fish together, read stories, and play baseball.” Brett, whose nose was buried in a plate of SpaghettiOs, glanced at my wife and said, “Hey, Mom, I think Dad got fired!”

The next day I was free of that daunting responsibility of reading all the

New York Times

editorials and every article in

Newsweek,

and gagging through Rush's show on the way home in the car.

It was fine with Barney, I thought. The chair was really not very comfortable in the studio. There were plenty of treats at home. Home. That had a nice sound to it.

A few months after my dismissal at the radio station, Sally, the sales rep who had so loved Barney and supplied him with daily treats, was diagnosed with cancer. During her illness, Barney and I visited her at home and on several occasions and when she felt up to it, she would show up at one of our morning segments. Barney recognized her perfume and would howl at the top of his lungs when she was within one hundred feet.

On one occasion, we went to the hospital to see Sally, but we were stopped at the elevator by a security guard who gave Barney the once-over. “Is he a service dog?”

“No.”

“Is he a therapy dog?”

“No, this is Barney from Channel 8,” I explained.

“Go right in,” said the guard, who broke into a huge grin. He had known it all along. Within five minutes, every nurse on the floor and several patients came to meet Barney.

Sally died six months later.

At the funeral, her best friend, Margo, asked if I had a photo of Barney in my car. When I retrieved the picture, she motioned me to accompany her to the open coffin. When we approached, Margo slipped the photo under Sally's folded arms. “I think Sally would have wanted this. She sure loved Barney.”

This felt like a kind of closure to the radio experience, bittersweet though, it was. I don't have many fond memories of my time on the radio, except I was happy that Barney had touched Sally's life. That seemed to make it all worthwhile. But what would you expect a bleeding-heart liberal like me to say?

Many people who might

have been reluctant to appear on TV were more open to the idea knowing that Barney was part of the mix. My favorite story is about Jerry Hostetler, then about sixty, and owner of the most garish house in town. His 55,000-square-foot home could have been charitably described as Vegas Gauche.

The modular structure had about fifty rooms, but that was just a guess because you really didn't know when one room ended and the next began. The house was filledâbut not decoratedâwith priceless antiques and works of art from around the world. Despite the value of his collection, the inside looked like a garage sale.

There were a dozen workmen on the premises 24/7, bowing to every whim Jerry had on any given day about the house. “Let's move the bathroom over there,” he'd tell a plumber, who never flinched. Why would he? He was being paid by the hour. The entire facility was a work in progress. If you could call it progress.

People in cars were always lined up on the street to see the house, which featured huge stone dolphin statues spouting water into a fountain on the front circle drive. Part of the allure was Jerry's past, which was probably a bit shady, but it always got shadier in the retelling. He was in the restoration business, so after a flood or fire, Jerry would haggle with the insurance companies over how much they would pay their clients. Jerry did very well at this. Too well, some thought, considering his house and furnishings.

But no one had ever done a story about the house because there were rumors he did not talk to reporters. He even shot at one, I had heard.

I was sure that wasn't true, but for years I had driven past the house, lacking the nerve to knock on the door. One day, Barney by my side, I took the plunge and pulled into his driveway. “Is Mr. Hostetler here?” I asked a gardener working on the front lawn. “Can I see him?”

“He's in the garage getting a manicure.”

Sure enough, there he was, decked out in a, well, deck chairâa beautiful Hispanic woman attending to his hair and nails next to one of his three Jaguar XKEs. I felt like I was meeting Howard Hughes.

Jerry was more than cordial, even self-effacing, admitting that he had heard the rumors about himself and assured me that

most

were not true. He even admitted to watching Barney and me on TV in the mornings,

before

he went to bed. As George Carlin once said, “The sixties were good to this guy.”

His good mood turned a bit sour when I requested permission to do a TV show about his unique dwelling. That temporarily ended the conversation, but he did assure me he would think about it and said I should call his secretary the next week.

When I called Carol, his assistant, she told me that Jerry wanted to make me an offer, which scared the hell out of me, but I listened. “You can do a show at Jerry's home, if he can hire someone to snap pictures of him and Barney together throughout the house.”

And so it was. Barney and I arrived two weeks later, greeted by Jerry's personal public relations man and a professional photographer. That's when we did the first live remote from the legendary residence. Barney had free run of the house and in one memorable shot, Barney was seen waddling down the wrought iron spiral staircase that led from one of the second-story party rooms to the living room on the main floor. Scarlett O'Hara, eat your heart out.

Jerry got his photos and I got my TV interview and tour.

Jerry died a few years after that. His houseâconsidered by neighbors an eyesoreâwent unsold for quite a while, but it is now the property of a young dot-com millionaire, new to town. When I had the occasion to meet the thirty-year-old owner, I told him the story I have recounted above.

“Who's Barney, again?” he asked.

Who, indeed!

Some people, like Jerry, may fear being on television. I have always said that there are two types of people: those who would do

anything

to get on TV, and those who would do

anything

to avoid it.

Here's some good advice for both groups:

Being on TV frightens people to death. In some ways it is scarier than public speaking. Of course, in a way, it is public speaking, but a camera seems even more threatening than a roomful of people.

When I arrived at a remote spot for Channel 8, I would request that everyone who didn't want to be on TV gather in a specific corner. Once the masses grouped to avoid media exposure, I began the segment by having my cameraman zoom in on all the huddlers who “didn't want to be seen on TV.” This caused a kind of mass hysteria, especially women who had arisen at 4:30 in the morning to bring their kids to the show and had skipped the makeup portion of their morning ritual. There was a lot of high-pitched screaming, back-turning, and huddling. Most were good-natured about it. Not all, but most.

It is really the talking on TV, not the being on TV, that petrifies everyoneâa fear of making a fool of yourself, saying something really dumb.

Case in point: In 1997, a nurse at the medical clinic at Indianapolis Motor Speedway was panicked about being

live

on the air to discuss how the ER treated race drivers who were hurt in collisions. I assured her that she was the expert and if she just relaxed she would be fine. I even told her what the first question would be.

“So, tell the viewers,” I asked during first segment, “what is the first thing you do if a driver is admitted to the ER with a head injury?”

“I'd take off his pants,” she said.

I think she was a bit nervous. Or a very friendly nurse.

Of course, now with YouTube and reality TV, there's a whole new generation of the public convinced that the dumber you appear on the screen or in a video, the greater the chances of being seen nationally and becoming a star or at least a topic of national conversation.

Back in the nineties, I happily capitalized on a goof with self-deprecation, calling attention to the misstep. Reporters with breaking news stories don't have this luxury. Even today, serious journalists don't want a YouTube moment if it compromises their professionalism.

Dealing with an individual's trepidation about being interviewed on TV is a responsibility I take seriously. Many of my guests have never been on TV or have had an unpleasant experience: a host who was not prepared, or asked bizarre questions, was distant or uninterested.

Barney truly made a difference in the minutes before an interview. Those who might have otherwise been total wrecks seemed to calm down a touch if they first interacted with Barney. While Barney's modus operandi usually involved sniffing his surroundings when we first arrived, he would ultimately come over to greet the guest and give a friendly wag. I wished he could have gone over some of the questions I was going to ask, but that was my job. Giving a guestâespecially one new to TVâsome idea of what the interview is about goes a long way toward making the experience less stressful. Unless it's an adversarial interview where your intent is to play gotcha, there is no excuse for the reporter not helping to prepare the interviewee. In my opinion, too many reporters and talk show hosts don't do this.

Having interviewed over 25,000 people in the past three decades, I do have tips for those who may someday find themselves on TV.

If you are reading this and have a memo on your desk to return a call to

60 Minutes'

Mike Wallace, forget this last paragraph and seek legal help. If you have something to hide, my tips will not help you. If you have clean hands, call Mike Wallace back.

Here are some things to rememberâthe three As.

Attitude: Being interviewed is not brain surgery, although if you have an MD or a PhD in neuroscience, the interview might be

about

brain surgery. You know more about your topic than the reporter or host, no matter how prepared he or she isâwhich is why you have been invited on the show to begin with. You are the resident expert on your topic, so relax and feel confident.

Answers: You are in control. No matter what you are asked, there are ways to get in the information you want to convey. Decide on a few things you want to say, a few points you want to make, and practice giving them in short, informative sentences. If you are truly not trying to hide anything and your answer is entertaining and informative, your interviewer will be happy.

Suppose, for example, that you have written a book about your travels around the world. Your favorite story is how you taught a polar bear at the North Pole to play the violin.

Q. So, Mr. Lewis, I understand you've been to the South Pole.

A. Yes, and it was glorious, but nothing compared to my incredible experience at the North Pole with a polar bear.

If the interviewer still wants to know about the South Pole after that, he's an idiot. Unless, of course, he has substantial evidence that you ran an illegal dog-sled operation at the South Pole.

Attire: Earth colors are best. Avoid black and white, which tend to wash out your face. Most people wear the right colors by sheer chance, so unless you are Zorro, a nun, or a member of the KKK, you'll be fine.

Men should always wear long socks. Even George Clooney has an ugly lower leg. No hats, dangling-jewelry overload, or chewing gum. These don't apply if you are there to talk about the return of the derby, sell cheap jewelry, or represent the short-sock fan club, but there is no excuse for gum. Also, ladies should not wear extra makeup and men will generally be given a little powder for the forehead if the interview is in-studio. If you sweat profusely because you're nervous, read this article ten times before doing the show. If you're completely bald, you will still look bald on TV.

If you're going on a talk show, get to the studio at least an hour early. Chances are, the producers will put you in a waiting area called a green room. In the green room (which is never green), you will have a chance to talk to other guests. If you discover that the host is a jerk, that his goal is to embarrass his guests, and that he has a horrible reputation for not keeping his word, you will then have time to sneak out.

In most cases, a producer will visit you in the green room. Tell the producer what you want to talk about. She or he will share this with the host. Some hosts will come by themselves and speak to you in person, but many think this ruins the spontaneity of the show. Bull! I've done it for thirty years. If your interview is of a personal nature, request, even demand, a short chat with the host beforehand. If you are being interviewed by a street reporter, still make an attempt for a personal conversation first. Again, some reporters and hosts won't do this, though it's sometimes an issue of time rather than preference.

Finally, some showtime tips:

Sit up: Most couches on sets are very soft. Once in Columbus, Ohio, we lost a guest in a beige couch for three days. Sitting up straight exudes an air of confidence. Don't slouch. If there's a fire alarm, two hundred thousand viewers will be watching you struggle to get up. Not pretty.

Speak up: The key to confidence is not to mumble. You will scare yourself to death if you whisper. Listen to the host's or reporter's voice. He may be a jerk, but he usually knows how loudly to speak.

Look up: Look at the host. Do not look at the camera. I am always amazed that reporters and hosts don't mention this to the guest. I've forgotten myself.

Avoid jargon: Change the pitch and tone of your voice to make a point. Talk pretty much the way you might in regular conversation. Don't be afraid to use your hands.

In summary, show passion. If you do not communicate that you had fun at the North Pole, no one will care how many polar bears you trained to play the violin. Success is all about sharing your enthusiasm.

Last but not least, be yourself. Unless “yourself” is a boring, aloof, self-centered, pompous egotist. But, of course, by definition, if that were you, you wouldn't be aware of it.

Once the interview is over, you may feel you mumbled, looked nervous, and said really stupid things. Watch the tape, and assuming your VCR or DVR was set correctly, you'll see it wasn't nearly that bad. If, however, you think you were the greatest and are considering writing to Oprah to be her fill-in guest host, it probably wasn't that good either.

If you videotaped

Girls Gone Wild

by mistake instead of the show where you talked about your new solar panels, give the station a call and ask for a copy of the interview on a DVD. They will be glad to help. For $129.95.