Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations (3 page)

Read Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations Online

Authors: Greg Kading

CHAPTER

2

Incident #7068000030

O

F ALL THE EVENTS

planned in conjunction with the Soul Train Awards that week, none was more eagerly anticipated than the Vibe magazine “after party.” If for no other reason than the sheer star power that promised to be in attendance, it was the place to be and be seen. Scheduled for the evening of March 9, the day after the televised presentations, there was only one choice for the gala’s venue: 6060 Wilshire Boulevard — The Petersen Automotive Museum.

Vibe was likewise ideally suited to host what promised to be the black entertainment industry’s soirée of the season. Launched in 1993 by the influential impresario Quincy Jones in partnership with Time Inc., Vibe had quickly established itself as the voice of the new breed of black artists. It pioneered coverage of rap’s astonishing emergence and the escalating controversy that accompanied it, providing extensive coverage on everyone from Snoop Dog and Lil Wayne to 50 Cent and the white rap phenomenon Eminem. The publication would put the full weight of its prestige behind the party, but to ensure that no expense would be spared for the evening, Vibe also enlisted an A-list of co-sponsors, including Tanqueray gin, Tommy Hilfiger clothing, and, for good measure, Quincy Jones’s own label, Qwest Records.

Planning for the evening began months beforehand, mostly under the auspices of Vibe’s special events coordinator, Karla Radford, who was based in New York. Radford had flown to L.A. to coordinate details with the Petersen staff. She walked the black polished floor of the Grand Salon, laying out seating arrangements and informing the museum’s event planners that she expected at least a thousand guests.

That number presented a problem, since capacity for the Grand Salon topped out at only six hundred. A solution was quickly found by securing the first floor gallery space, with room for an additional six hundred to accommodate those further down the celebrity food chain. Additionally, and in keeping with the unending concerns for security that surrounded the Soul Train festivities, Radford retained the services of Da Streetz, Inc. The private protection firm was meant to augment the museum’s own security staff, and before the arrangements were complete, yet another guard would be borrowed, from the Natural History Museum.

But in hindsight, Radford’s preparations seem woefully inadequate. Even with the addition of another guard, the security contingent totaled a mere ten. What was lacking in manpower would supposedly be made up for by state-of-the-art technology. The museum had several time-lapse surveillance cameras to monitor activities on all four floors, as well as each level of the parking garage, all overseen from a console at the museum’s front desk.

Radford, however, seemed more focused on the celebrity contingent than the security contingent. The night before the party, in the midst of the awards program at the Shrine Auditorium, she had circulated among the audience, handing out invitations to any and all of the famous faces she saw. Among those who had the glossy invitation pressed into their hands were the actor Wesley Snipes, the British soul singer Seal, the New York Jets wide receiver Keyshawn Johnson, the Detroit Pistons forward Grant Hill, and a raft of rappers that included Jermaine Dupri, Da Brat, and Heavy D. Before the show was over, she had also managed to buttonhole Puffy Combs and Biggie Smalls.

But Radford was hardly depending on chance encounters to pump up the evening’s star quotient. Word of mouth had been spreading for weeks in advance of the Vibe extravaganza. By the time the Petersen opened its doors at 9:00 on a clear dry night with temperatures hovering at a balmy 60 degrees, the turnout was proving to be nothing short of spectacular.

Professional and amateur celebrity spotters, not to mention the LAPD, would later compile and compare lists of attendees that read like a Who’s Who of black entertainment, sports, and business. Radford had done this aspect of her work well: it was an impressive showing by any reckoning. In order to check invitations and greet the assorted VIPs, she strategically placed herself at the sweeping glass doors of the museum’s entrance, located at the rear of the building. The broad driveway leading to the foyer had access onto both Fairfax and South Orange Grove Avenue, a small semi residential street along the east side of the museum. Its massive overhang, decorated with the flags of auto-manufacturing nations, linked the building directly to its parking structure. Here, limos deposited their passengers while a large and growing crowd of spectators strained at the rope line, their excited shouts greeting each new arrival.

Among the jostling throng were five friends from Houston, Texas who had made the long trip west in a 1982 Chevy 4 x 4 van, specifically to spot stars during the Soul Train celebrations. Devoted rap fans, they had gotten word of the Vibe party and made their way to the Petersen, where they found a bird’s-eye view, parked directly across Fairfax Avenue from the museum entrance. They waited expectantly, in hopes of seeing some of their favorite performers.

Despite the mob at the entrance to the Petersen’s covered esplanade, they weren’t disappointed. Along with such instantly recognizable personalities as the actress Vivica Fox, the Def Jam regular Chris Tucker, the comic siblings Keenan and Marlon Wayans, the NBA superstars Derek Fisher and Jamaal Mashburn, and the soul divas Whitney Houston and Mary J. Blige, invited guests also featured those better known for their rhymes and rhythms than for their faces. As the evening progressed, a contingent of aspiring rap newcomers basked in the flash of cameras and the adoring crowd. Mase, Case, Ginuwine, Missy, Yo Yo, Spinderella, Nefertiti: even these fledging stars arrived with a substantial entourage in tow. The local rapper and Death Row recording artist DJ Quik, for example, was accompanied by a phalanx of no less than a dozen friends and hangers-on, all of whom were duly waved through. The guest list was quickly getting out of control, but there was little Radford could do about it. Everyone had to be afforded the perks of full celebrity status, whether they had earned it yet or not. Who knew which of them might be the next Biggie Smalls?

The man himself, meanwhile, was very nearly a no-show. Worn out from his hectic Los Angeles schedule, Biggie began the day by trying to beg off the event, telling Puffy that he simply wanted to relax and enjoy the California sunshine. As if to underscore the point, he spent most of the rest of the day in the company of Lil’ Caesar and Paul Offord at another in the series of Soul Train-related events set for that week; a celebrity charity basketball game at Cal State Dominguez Hills.

It was late that afternoon when he got a call from Puffy. Biggie needed to represent at the Petersen, Combs insisted. He had to show the world that he hadn’t been rattled by his reception the previous night at the Soul Train Awards. But it was the networking possibilities afforded by the party that finally brought the rapper around. “Let’s go to this Vibe joint,” Combs later recalled Biggie saying. “Hopefully, I can meet some people, let them know I want to do some acting.” The decision, Combs would assert, “made me proud; he was thinking like a businessman.”

But before he could make it to the Petersen, an event promoter from Camden, New Jersey, named Scott Shepherd buttonholed Biggie in his suite at the Westwood Marquee. A whole different kind of businessman, Shepherd was one of the swarm of opportunists operating at the fringes of the entertainment industry. He had tailed Biggie to California, intent on pitching a bizarre scheme to celebrate the star’s birthday with a series of parties across the country.

Arriving at the hotel with Shepherd was another would-be entertainment entrepreneur looking to cash in on Biggie’s fame. Ernest “Troia” Anderson was a freelance screenwriter desperate to make a feature film biography of the rapper under the auspices of Bad Boy Films, a division of Puffy’s empire that as yet existed only on paper. Teaming up with his colleague Shepherd, they had driven to the Westwood Marquee in Anderson’s 1995 white Toyota Land Cruiser, a vehicle that would play an unlikely role in the chaotic events about to unfold.

Shepherd and Anderson managed to attach themselves to Biggie and his posse as they left the hotel that evening in a convoy composed of two green Chevy Suburbans and a black Blazer, all 1997 model year rentals. The hapless duo followed in Anderson’s vehicle, assuming they were on their way to the Vibe party as special guests of the Notorious B.I.G. Instead they wound their way up into the Hollywood Hills above Sunset Strip, arriving at a sumptuous mansion owned by Andre Harrell, founder of Uptown Records. Harrell had given Puffy his first big break in the music business and now had lent Combs the plush spread for the duration of his stay of Los Angeles.

Puffy was waiting, ready to get the evening started, and neither Shepherd nor Anderson had a chance to pitch their respective schemes before the caravan got rolling again. They followed close behind, relishing their new roles as privileged players in Biggie’s inner circle.

It was a big circle. Eleven men accompanied the rap star that night. Along with Puffy and Lil’ Caesar, the group included an assortment of childhood friends, aspiring rappers, and business associates. The security contingent was headed by Ken Story, Reggie Blaylock, and Paul Offord, who oversaw a squad of Bad Boy bodyguards composed of Gregory “G-Money” Young, Damien “D-Roc” Butler, and Lewis “Groovy Lew” Jones, as well as Eugene Deal, Steve Jordan, and Anthony Jacobs.

Arriving shortly after 9:30, just as the party was getting under way, Biggie, Puffy, and company, with Shepherd and Anderson slipping in alongside, were greeted with a blinding barrage of photoflashes. The spontaneous roar from the crowd was easily the loudest of the evening. At Karla Radford’s signal, the doors swung wide and they were escorted to the second-floor Grand Salon, their security detail plowing through the crush of ogling partygoers that were already starting to fill the ground-floor galleries.

While Biggie usually favored boxy, three-piece designer suits topped by an expensive felt bowler hat, he was making a different, and decidedly more downplayed, fashion statement for the occasion, dressed in faded blue jeans and a black velour shirt. He also sported sunglasses and the gold-headed cane he had been using since the car accident that shattered his left leg during the recording of

Life After Death

. A large gold medallion etched with the face of Jesus was hung around his neck, replacing his usual pendant, which featured the branded Bad Boy icon of a glowering baby in a baseball cap and construction boots.

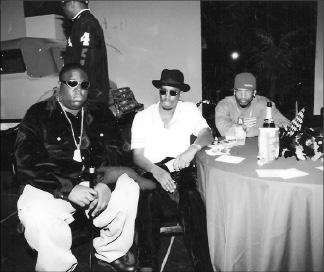

Biggie Smalls and Puffy Combs at the Peterson VIBE party, March 9, 1997, shortly before Biggie was gunned down.

Photo Credit:BlackImages Archives

God and religion had, it seemed, been much on Biggie’s mind in recent weeks. He had worn a conspicuous crucifix to the Soul Train awards and while in L.A. had gotten a tattoo for the first and only time, choosing a lengthy passage from Psalms 27 rendered as a scroll of tattered parchment on his massive forearm. “

The Lord is my light and my salvation,

” the ink read, “

whom shall I fear? The Lord is the truth of my life, of whom shall I be afraid? When the wicked, even my enemies and foes, came upon me to bite my flesh, they stumbled and fell

.”

Exaltation and excitement greeted him as he made his entrance into the Grand Salon, taking a ringside seat in a corner booth beside the dance floor as the DJ slipped “Hypnotize” onto the turntable at full volume. It would be played eight more times consecutively, and at frequent intervals thereafter, as the rapper received the honors and accolades of the crowd. He beamed happily, sipping Cristal champagne and taking hits on the pungent blunts that were passed his way. Women would break from the mobbed floor to dance seductively before him, and a raft of celebrities dropped by to bask in his glow. Among the many was Russell Simmons, the pioneering founder of Def Jam Records.