Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations (8 page)

Read Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations Online

Authors: Greg Kading

But it was an LAPD detective named Russell Poole who had put forward what was, by far, the most compelling and convincing theory of what really happened and why. It was simple and elegant and fit the agendas of many of the factions that saw the death of Biggie Smalls through the lens of racism, class warfare, and the long-standing mistrust of the entrenched powers that ran Los Angeles. Simply put: the cops did it.

In every important way, Poole was a quintessential police officer, which gave his allegations of a conspiracy within the force a convincing ring of truth. For many involved in the case, he became the ultimate whistleblower, an insider with the courage to bring down the organization to which he had dedicated his professional life.

The son of a veteran L.A. County sheriff, Poole began his law enforcement career in 1981, rising quickly through the ranks to make detective in 1987 and detective supervisor in 1996. He would work as a homicide investigator at South Bureau, Wilshire, and the Robbery-Homicide Division for over nine years and was the primary detective on hundreds of cases. He helped to solve the 1997 murder of Ennis Cosby, son of comedian Bill Cosby, and was a part of the team that investigated the bloody North Hollywood bank robbery shootout that same year. Highly respected and much decorated, Poole was a cop’s cop, a consummately professional officer with tireless dedication and a firm belief in his own capabilities.

Poole’s role in the Biggie Smalls case began nine days after the death of Christopher Wallace in a context completely unrelated to the murder itself. He and his partner, Fred Miller, had been assigned to the homicide investigation of LAPD officer Kevin Gaines. Gaines, who had a history of aggressive behavior, had been killed when he instigated a road rage incident with another cop, an undercover detective named Frank Lyga. The cop-on-cop incident had a complicating racial element to it: Gaines was black and Lyga was white. There were some within the force, mostly friends and former partners of Gaines, who had immediately accepted the racial motivation and launched their own unofficial investigation to prove it. But for Poole, the significance of the case reached far deeper.

Early on in his probe, Poole discovered that Gaines had a girlfriend named Sharitha Knight, the estranged wife of the Death Row Records founder, Suge Knight. Following his instincts, Poole began to look closely at the dead officer’s background, discovering among other intriguing details that Gaines favored expensive suits, drove a Mercedes, and frequented Monty’s Steakhouse, a Westwood restaurant known as a Death Row hangout.

It was at that point that Poole felt he had “something different from your ordinary investigation…” What that “something” would turn out to be was an elaborate triangulation of rap, gangs, and corrupt cops, leading Poole to believe that Gaines had direct links to Death Row criminal activities. “He crossed the line,” he would later assert in a 2001 interview with

Frontline

. “He tarnished the badge.” And Gaines wasn’t the only one to eventually be implicated in Poole’s comprehensive conspiracy theory.

A month after the Biggie killing, the investigation — which up to then had been handled by Wilshire detectives — was handed over to the Robbery-Homicide Division. Russell Poole was named as one of the two lead detectives. From that point on, Poole assiduously worked to uncover any connection he could that might link the two investigations.

For all the lack of solid evidence or suspects, a theory of sorts had taken shape by the time Poole came aboard. As an early progress report stated, “The investigation has revealed the possibility of an ongoing feud between the victim’s recording company (Bad Boy Entertainment) and Death Row Records owned by Marion (Suge) Knight. The feud is fueled by the fact that Death Row is made up of Blood gang members and that Bad Boy is comprised of Crips…”

That wasn’t entirely true. Puffy’s supposed use of Crips as security for concert appearances on the west coast hardly constituted membership in the gang. But at least the outlines of a workable hypothesis were emerging, one that Poole would take to with avid interest. He had already turned his focus to Suge Knight as a result of the Gaines case. From that point on, the two investigations were inexorably linked in his mind.

That link would only become more substantial to Poole as he continued to delve into the circumstances of Biggie’s killing, persuading himself that the drive-by outside the Petersen was a sophisticated operation far beyond the capabilities of local gangsters to plan and execute.

“Since starting on the Biggie Smalls case,” he would later tell Randall Sullivan in

LAbyrinth

, a 2002 book recounting Poole’s theory of the murder, “I had kept coming across these crime reports in which the perpetrators used police radios and scanners…Suge Knight and his thugs had used them to monitor the cops…There were all these reports of the Death Row people using them in and around their studios in Tarzana.” The reports were significant to Poole given the fact that, in the aftermath of Biggie’s shooting, there was a persistent rumor that police radios had been used as part of a precision operation.

Witness reports of hearing scanner chatter outside the Petersen was not the only indication to Poole of a criminal conspiracy. There was the intriguing question, for instance, of how the shooter, alone in the black Impala a block away from the museum entrance, would have known exactly which vehicle Biggie had gotten into and what seat he occupied through the heavily tinted windows. The random gunfire from the Chevy Blazer on South Orange Avenue heard earlier in the evening could well have been a diversion to distract police and security guards from the real target. Poole’s investigation was taking on a life of its own and the veteran cop was sure he was on to a major breakthrough. The dimensions of that breakthrough were about to be expanded by an order of magnitude.

In late 1997, while Poole was still actively working both the Gaines and Wallace investigations, the shocking news broke that a police officer had been arrested for a bank robbery that had netted $722,000, one of the largest heists in the city’s history. His name was David Mack, a veteran officer of the Los Angeles Police Department. He and his one-time partner Rafael Perez would soon vie for the dubious distinction of being the most infamous rogue cops in America.

Following his arrest, Robbery-Homicide investigators began digging extensively into Mack’s background. A search of his house turned up the Tec-9 he had used in the robbery as well as a large chunk of cash under the carpet. But when Russell Poole caught wind of what else had been uncovered, other crucial pieces of the puzzle he had painstakingly been assembling appeared to fall precisely into place.

First and foremost was Mack’s black Chevy Impala, driven in the bank robbery but also — and of incalculably more significance to Poole — the same make of vehicle used in the Biggie drive-by. As if that were not enough to underscore Poole’s belief that he had a major conspiracy between cops and gangsters on his hands, there was the bizarre discovery of what investigating officers described as a “shrine” to Tupac Shakur in Mack’s home, an altar of posters and paraphernalia devoted to the slain rapper. Equally tantalizing was a tailored suit of bright crimson that had turned up in the outlaw cop’s extensive wardrobe. Red, of course, was the Blood gang color and the outfit was nearly identical to one worn by Suge Knight. On top of that were the telling entries in the Rampart duty log, detailing a number of sick days Mack had taken just prior to Biggie’s murder.

Yet another key clue for Poole had to do with the fact that David Mack was an avowed Muslim. More than one eyewitness to the Wallace murder had described the shooter as dressed in a suit and a bow tie. It was the bow tie, the same neckwear favored by Black Muslims, which added crucial weight to Poole’s conjecture of an LAPD/Nation of Islam/Death Row conspiracy to kill the rapper.

That conjecture was furthered when Kevin Hackie, a former Compton School Police Department officer facing forgery charges, came forward with the claim that Kevin Gaines, David Mack, and Rafael Perez were part of Suge Knight’s extended posse. Even if none of these cops turned out to be the actual killer, Poole reasoned, they would certainly know who was and had perhaps participated in coordinating the hit, possibly with assistance from the Fruit of Islam.

As he pushed further into the thickets of these intertwined investigations, Poole became increasingly convinced that he was being met with determined resistance from the LAPD brass. It was a case of the circular logic of conspiracy: if your theory is rejected, it’s because the doubters are among the plotters, which in Poole’s version of the conspiracy included the recently appointed chief of police himself, Bernard Parks. Poole had grown impatient with the reluctance of the department to investigate the link between David Mack and Suge Knight. Any attempt he made to move the sprawling investigation in that direction was rebuffed in no uncertain terms and he took that as a sign that the brass was stonewalling a major scandal within the department.

But there was another explanation to the official reluctance to follow Poole’s leads. Before he was named to head the department, Parks had been an LAPD deputy chief whose duties included overseeing all investigations by Internal Affairs. If anything qualified as an IA matter, it was David Mack’s criminal misconduct. As with any case that fell under the purview of Internal Affairs, all findings were subject to a near-complete information embargo. Nothing that IA might discover during the course of its investigation could be revealed to other detectives, no matter how important it was to their ongoing work. It was a necessary restriction: Internal Affairs officers were charged with investigating their own and had to factor in the distinct possibility that where there was one corrupt cop, there might be others, trying to deflect or derail their work. A wall of silence was accordingly erected even as Poole persistently attempted to breach that barrier.

In a way, I can understand his frustration. I’ve been in his shoes, cut off from potentially valuable information to which only IA was privy. But that’s the way the system works and it’s something any detective has to come to terms with. What Poole saw as a concerted cover-up was instead a well-established precedent, making clear distinctions among all the various investigations in which he had become involved. Taking down David Mack was not Poole’s responsibility. That responsibility belonged to the FBI, which was investigating Mack’s involvement in the bank robbery. Poole’s responsibility was to find out who had killed Biggie Smalls. If the cases converged, the preponderance of evidence would reveal the connection. Until such time, it was Poole’s duty to stick to established protocols.

Poole didn’t see it that way. In hindsight, evaluating the veteran detective’s investigative work as he delved ever deeper into a remarkable string of circumstances, is not an easy task. His version of events — the means, methods, and motives of the Biggie Smalls murder — seemed to fit together perfectly. What was ultimately lacking was objectivity. He

wanted

to believe, and that desire, in my opinion, compromised his judgment.

The proof of that lapse can be seen, as the investigation proceeded, in Poole’s reliance on jailhouse informants to support his case. In the spectrum of data-gathering techniques utilized by law enforcement, the stories told by anyone serving time are considered tainted by their very nature. While it’s true that informants behind bars can, and often, do come up with useable information, it’s always important to check and double-check what they tell you. Inmates have little to lose and much to gain if they can appear to be cooperating with authorities by passing along valuable information. Knowing this rule of thumb, Poole ignored it as his peril.

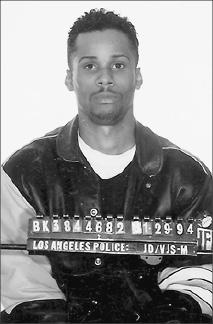

Mug shot of jailhouse informant Waymond Anderson, whose tall tales would lead the investigation down several frustrating and futile rabbit holes before the truth behind the murder of Biggie Smalls was finally uncovered.

The first informant to come forward in the Biggie Smalls case, a mere three weeks after the murder, was Waymond Anderson, a former R&B singer who went by the stage name of Suave and was charged with first-degree murder for setting a house on fire and incinerating its resident. Awaiting trial at the L.A. County Jail’s Wayside facility, Anderson stepped forward claiming to have information relevant to the Christopher Wallace case and hoping to exchange it for a lesser charge or a reduction in his sentence.

While in a holding tank at the Inmate Reception Center downtown, he told Wilshire detectives, Suge Knight, who was also being processed at the facility for a parole violation, approached him. According to Anderson, Suge induced him to use his gunrunning contacts to supply the weapons for the Biggie hit. He even told Anderson the names of the designated hit men: Knight’s associate Wesley Crockett, his cousin Ricardo Crockett, and an ex-Compton police officer named Reginald Wright, Jr.