My Life So Far (32 page)

Rita Martinson, Donald Sutherland, and me during the FTA show.

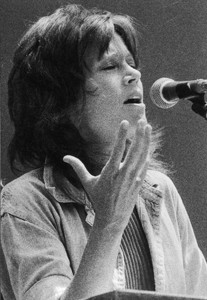

Talking . . . always talking to end the war.

At Laurel Springs with Tom, Troy, Vanessa, and her dog, Manila.

(© Steve Schapiro)

The night Tom won his race for the assembly. Left to right: Margot Kidder, Tom, me, Shirlee.

(Barry E. Levine)

The Workout.

(Harry Langdon)

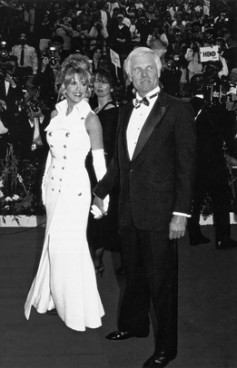

At the Oscars with Ted. At this point, he’s the one in show business.

(Michel Bourquard/Stills/Retna Ltd.)

Surveying the bison on Ted’s ranch.

CHAPTER ONE

1968

If a butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil, it might produce a tornado in Texas. Unlikely as it seems, the tiny currents that a butterfly creates travel across thousands of miles, jostling other breezes as they go and eventually changing the weather.

—E

DWARD

L

ORENZ

O

KAY, SO I WAS WRONG.

My life didn’t peak, nor was it on the decline. But like everything else in the world, it was about to go through major changes. Looking back, I believe it now seems fated that I began my second act in 1968

,

perhaps the most turbulent, tumultuous year of the century. I was thirty, pregnant, and ripe. Everything in me was poised, like a sprinter at the starting line, twitching to move forward.

Things had been brewing for a while: I needed to make sense of life and feel I had a purpose. Filming

Barbarella

at a time when so much substantive change was taking place in the world had acted as yeast to my malaise. Who was I? What did I want from life? I am carrying life—what does this mean for me?

Change always holds an element of self-interest, and mine was quite simply that I wanted to be a better person. To switch to a gardening metaphor, it’s possible that the seeds of my definition of “better” were gathered and planted way back when I saw my father’s early movies:

The Grapes of Wrath, The Ox-Bow Incident, Young Mr. Lincoln.

Stratified after thirty years, they were now waiting to sprout. My pregnancy during that fertile year—1968—created a rich loam.

A

t first the evidence offered by my pregnancy (that I was a woman, hence like my mother) had struck terror in my heart, but as time went by, the fear gave way to a strange peace. Peace was not something with which I was familiar. Perhaps the hormones of pregnancy were washing away my lifelong tendency to depression. But I think it was more than that. I believe that in facing and naming the terror I had felt at the start of my pregnancy, a healing process had been set in motion—a somatic realization that I was, in fact, a normal female. My always troublesome “down there” was doing what millennia of women’s down theres had done for them. I had conceived. In a way, I was pregnant with a baby and also with myself, connected by a primordial umbilical cord to other women—to all women past, present, and future; to the female spirit—interested in and needing to be with women more than men for the first time since adolescence. In fact, during my nine months of pregnancy I experienced being

in my body

for the first time since

pre

adolescent girlhood. I would not be capable of sustaining that embodiment after pregnancy, but I would find it again later, in my third act.

I

had never gone in much for watching television and was not one of the many Americans witnessing the developing Vietnam War from their living rooms. What attention I did give to it allowed me to remain comfortable in the belief that it was an acceptable cause—maybe not a “good war” like the one my father fought in; more of a fuzzy one, like the Korean War. But all that changed when the risk of miscarriage confined me to bed for the first three months of 1968. I saw images on French television showing damage caused by American bombers that, en route back to their aircraft carriers, unloaded bombs they hadn’t already dropped, sometimes hitting schools, hospitals, and churches. I was stunned.

Then, beginning in January during the celebration of Tet, Vietnam’s new year, the North Vietnamese and Vietcong launched a series of well-coordinated offensives in major cities throughout South Vietnam. It was shocking. For this to have been organized and carried out without the U.S. military and our allies having even a hint meant that the people we were calling the enemy was just about everybody. As I watched the Vietcong storm the grounds of the American embassy, it occurred to me that Vietnamese residents throughout Saigon must have participated: shopkeepers, peddlers, farmers, laundresses. Later it was discovered that guns, ammunition, and grenades had been smuggled into the city in laundry and flower baskets. The words of General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, claiming that he was close to ending the war, that he could see “a light at the end of the tunnel,” echoed grotesquely in light of what we were seeing on television. We, supposedly the mightiest military force in the world, had so lost ground that even after four years of warfare the enemy was able to attack us in our own embassy.

The psychological impact of such images was devastating. Everything was turned upside down. Who was strong? What did “military might” mean?

Who were we as Americans?

As I lay in bed contemplating what I was seeing, I remembered a morning in Saint Tropez. Vadim and I were having a leisurely breakfast on the balcony of our room at the Tahiti Hôtel when he opened the newspaper.

“

Ce n’est pas possible! Mais ils sont fous ou quoi?

” he exploded, jabbing his fingers at the front page. “Look at this. Your Congress must be out of their minds!” It was August 8, 1964, and French headlines blasted the news that Congress had just passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. It gave President Johnson the power, for the first time ever, to bomb North Vietnam.

“There’s no way you can win a war in Vietnam!” Vadim continued with uncharacteristic passion.

I wanted to ask, “Where

is

Vietnam?” but I was too ashamed. I also wondered why he was so certain the United States couldn’t win, and I felt defensive. Sour grapes, I thought. Just because the French lost . . .

Now, with the grim reality of 1968 and the Tet offensive, it occurred to me that Vadim may have been right. But how could the United States lose to a country so small? And if a French filmmaker had known in 1964 that we couldn’t win, why did the American government fail to get it? It would take me four more years before I really understood why Vadim had been so certain, and a few years after that to begin to grasp the most disturbing question of all: why five administrations, from Truman to Nixon,

did

see that we couldn’t win and persisted anyway.