My Story (19 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

This but returns to the original conception of the railway, and indeed to almost every other form of highway, such as country roads, streets, turnpikes, canals, rivers, lakes and the ocean, in which the public owns the way and on which the business of transportation is left to private enterprise, subject of course to control and direction of public officials.

And just as toll-bridges are giving way to free bridges, and toll-gates disappearing from turnpikes and canals, so, in pursuit of economy, the minimizing of the numbers of government officials and the removal of temptations to fraud, should the steam highways be open to use without charge, the expense of maintenance being made a public burden, as is the tendency to treat all other public highways.

But if I were ambitious to rule a country absolutely, I should not try to get control of its railroads even under the present system when, as we have seen, one-man power can be carried to such great lengths. I should devote myself with singleness and tenacity of purpose to becoming its landlord. The ownership of railroads gives power as, and only as, it is really ownership of land; the power of street car companies is based on the same thing, privileges

in the ownership of streets which is land; the power of the Standard Oil Company rests upon the right of way for its pipe lines, and that right of way is land. A man who controlled all the land of a country would be the ruler of that country no matter who made its laws or wrote its songs.

If this is true why does it not indicate to the people their own source of power? If a tyrant can rule them by gaining control of the land of their country, why cannot they destroy tyranny by themselves resuming and retaining control of their land?

But we must have a method whereby this can be accomplished and the method, I believe, is in the single tax as Henry George's philosophy is commonly called in this country. The single tax proposes the abolition of all forms of taxation except a tax upon land values. It would eliminate taxes upon industry, personal property, buildings and all improvements. It would tax land values, including the value of all franchises and public utilities operated for private profit. It is the community which creates land values and franchise values, therefore these values belong to the community and the community should take them in taxation.

To abolish taxes on industry would be to reduce friction in making things and trading things. It would stimulate business and be a blow to tyranny, both economic and political. The effect of a tax upon land values would be to force all needed land into immediate use, and circumstances would be created under which anybody could get profitable work who wanted it. This would be because the demand for labor would always exceed the supply. Any man competent to do business could find profitable

business to do because the effective demand for goods would always exceed the output. There could be no oppressive organization of capital, because capital would have no privileges. There could be no coercive labor unions because every worker would be his own all-sufficient union. And there would be no tyrannical government because all the people would be economically free, a condition that makes tyranny, either economic or political, impossible.

These are the principles which must be put into practice if our cities and our States are to be freed from the domination of Privilege.

GOVERNMENT BY INJUNCTION

O

UR

movement early commenced to have an influence outside of Cleveland, and it was in the midst of my first mayoralty campaign that I received a call from Columbus, the State capital, to help in a contest then going on between that city and its street railroad company. I had my hands pretty full in Cleveland, but I went down to Columbus to give such assistance as I could, taking Professor Bemis with me.

Some of the grants to the Columbus Street Railway Company had been made before the State legislature passed a law which limited the life of all street railway franchises to twenty-five years. Some of them had already expired, some had been granted without date of expiration. A citizens' committee of twenty-five and sixteen out of the nineteen members of the city council invited me to address the council committee of the whole on the street car question. I made a number of speeches which, combined with the articles which appeared daily in the Columbus

Press Post

from Professor Bemis's pen, did something to enlighten the citizens on the real status of the street railway controversy.

I offered to take the grants on favorable terms, fair to the old company, agreeing to buy the physical property, the valuation to be reached by negotiation or arbitration, and to operate at three-cent fare. The council refused to

consider my proposition and the grant was made to the old company, but so amended as to provide for seven tickets for a quarter until the receipts of the company should amount to $1,750,000 annually, and then the fare was to be reduced to eight tickets for a quarter. The courts upheld the validity of this grant, but the condition of eight tickets for a quarter has never been complied with. Whether the street railroad company has actually swindled the public or whether they have shuffled the bookkeeping in such a way as never to reach the limit I never have been able to find out. At a five-cent fare Cleveland was taking in $6,000,000 a year, so it is perfectly clear, after allowing for the difference in population in the two cities, that Columbus couldn't fail to reach the mark of one million and three-quarters.

The judge who rendered the decision in favor of the street railway company, holding that some of their grants were perpetual unless the legislature repealed them, was Judge A. N. Summers. Several months before his decision was made public a number of us learned what it would be. My knowledge of it came to me in a confidential way so I could not make it public. Stock advanced from a very low price to a very high figure while this case was pending. It was long drawn out and between the time that the decision was known and the time that it was made public the Republican State Convention of 1903 was held and nominated Judge Summers for the supreme bench. In the State campaign that year I publicly made charges against Judge Summers and offered to divide my time with him or any representative he might select to come to any of our meetings and explain this remarkable transaction. The judge never answered me on

the stump. His friends said the knowledge of the decision leaked out through a stenographer. My charge was that stock gamblers were profiting by this knowledge on the one hand and the judge on the other since he was receiving the support of the public service corporations in his campaign. I insisted that whether his position was due to carelessness or to viciousness the people ought not to elect him to the high office of supreme court judge. He was elected. This is a way public service corporations have of rewarding faithful servants. When all is said and done, I think he was not much worse than the rest of the court and a rather better lawyer than most of them. The people had not been sufficiently aroused to hold judges accountable for their actions. Ohio elects her supreme court judges for six years and by reason of changing from annual to biennial State elections Judge Summers's term held over an additional year. It was not until the last State election (November, 1910) therefore that he was a candidate for re-election and then he was defeated. The people are beginning to wake up and Privilege is finding it somewhat more difficult to bestow rewards of this kind now than ten years ago.

While the activities described in previous chapters in behalf of the equalization of taxes and the promotion of public improvements and good government were going forward the other promise of our platform â to try to give three-cent fare on the street railroads â was not neglected. The people looked upon this as

the

important question, but in the beginning comparatively few of them realized the intimate relation between it and all the other problems we were trying to solve and they did not in the least comprehend the difficulties in the way. There

were many who clamored for the immediate redemption of the three-cent fare pledge without taking into consideration the legal obstacles which blocked our path or the almost insurmountable barrier which the coalition between the public service corporations and the courts presented.

It will be remembered that Cleveland's street railways were at this time controlled by two companies, popularly known as the Big Con and the Little Con. The last named was Mr. Hanna's company and the Big Con was the result of the consolidation of the Andrews-Stanley interests with my lines. As has already been stated I had sold all my Cleveland street railway interests in 1894â95. The contest to secure three-cent fare was between the city and these two companies which had a common interest in opposing anything which threatened their monopoly of the city's streets. They acted as a unit and in 1903 they consolidated. The reader will be less apt to be confused if these interests are referred to from the beginning as one company and this I shall do.

The State laws had been carefully framed and as carefully guarded to protect existing street railroads in their privileges and to prevent competing lines, and it was only through competition that we could hope to secure a reduction in fare.

There were three ways in which grants could be made and we shall consider them in the order of their respective advantages to Privilege.

The first and easiest provided for the most valuable form of street railway franchise, namely, the renewal of an expiring grant. This could be made only to the company in possession of the grant and was not hampered by restrictions of any kind.

The second provided for extensions to existing lines and required consent of property owners along the proposed route.

The third, for making grants for new lines, was so complicated as to make it next to impossible to build a competing railroad.

These were the legal conditions which faced us, and it must be remembered that they were prescribed by State statutes and that the municipality had no recourse but the courts, and the courts, as has already been shown, were operating in the interests of the public service corporations. We were undecided as to which was the wiser course for us to pursue,â to have council make a grant covering a number of streets, or one for a small branch from which future extensions could be made. As the question of grants for new lines had never been tested in the courts we felt pretty sure that we should be defeated no matter which horn of the dilemma we took. We had not only to decide upon the policy of the administration, but to find someone to whom the grants could be made who would not only be able to finance the enterprise but whom we knew to be absolutely trustworthy.

On December 6, 1901, there was introduced into the city council the first legislation for the establishment of new street railroad routes upon which the rate of fare should not exceed three cents. On February 10, 1902, one bid was received, accompanied by a deposit of fifty thousand dollars. This bid came from J. B. Hoefgen, a man who got his first street railroad experience with me in Indianapolis years before, and now an independent operator located in New York. He was declared the low bidder and the grant was made to him March 17,

1902. We knew he wouldn't sell out to the old company or fail to keep faith with the city in any other way. The making of this grant, which covered a large number of streets, had been preceded by a property owners' consent war extending over several months. Representatives of the street railways followed closely on the heels of the men who were getting consents for Hoefgen and brought every possible pressure to bear to have these consents revoked. It was like a game of battledore and shuttlecock with an organized force playing it for each side. The courts held that property owners had a right to change their minds up to the time the ordinance was passed. Some of them did so seven or eight times or as often as they were paid to. The Hoefgen Company finally secured a lot of consents at the eleventh hour and turned them in just before the ordinance was passed when it was too late for the railroad companies to secure revocations.

Council could not make a valid grant unless a majority of the property owners representing the feet front along each street of the proposed routes consented in writing to the construction of a street railroad, and then only to the company offering to carry passengers at the lowest rate of fare. If the street railroad company, through property owners' consents, could get control of just one street in a group of streets to be covered by proposed new lines council was rendered helpless, and though a majority of the citizens of the entire city favored the new grant they had no way of giving expression to their will in the matter.

To overcome this difficulty we early found it necessary to change the names of streets. The three-cent line in question was to run upon Hanover, Fulton, Willett streets and Rhodes avenue, a continuous thoroughfare

with four different names. The low fare people had a majority of consents on Fulton street and Rhodes avenue, but lacked a majority on Hanover and Willett. Council changed the name of the entire thoroughfare to Rhodes avenue and in this way wiped out the minority on Hanover and Willett with the majority on Fulton and Rhodes. This method of attack or defense was persisted in pretty thoroughly by the administration.

When the courts declared the Hoefgen grant invalid, as of course they did, we asked to have this order made final. We wanted to clear the way for immediate action in another direction. This done, we now proceeded to try the alternative previously alluded to. We picked out eleven routes and required a bond in the form of a cash deposit of $10,000 to be made with each bid. This made it necessary for the old company, as a matter of self-defense, to be the lowest bidder on all ten routes, and to put up a deposit of $110,000. The new company had only to succeed on one and to put up a deposit of $10,000. Having secured a grant on one route they could secure further grants as extensions to their original line. No deposits were necessary on extensions though property owners' consents were required.

I was using, in the interests of the city, exactly the same methods to secure grants for the low fare people which the Hanna-Simms Company had used to prevent grants to me when I was seeking them as a street railway operator back in

1879. This plan was persisted in and was the one which eventually won the victory for the city and vindicated our campaign promises. And by a curious coincidence too the first three-cent grants were for routes over part of the same territory that was involved in that 1879 contest.

But before we were successful many extraordinary things happened, not the least of which was the practical destruction of the city government of Cleveland.

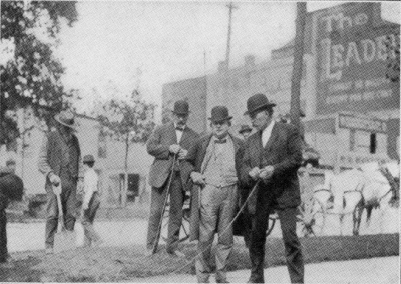

Surveying at Franklin Circle for three-cent fare line

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

Laying the first rails for the three-cent line

Privilege was thoroughly aroused now, and had evidently arrived at the conclusion that safety from our agitation was to be secured only by killing it and everybody connected with it. Two days after the first three-cent fare ordinances were introduced in the city council a press dispatch reading as follows was sent out from Columbus:

“December 8, 1901.

“A suit to test the constitutionality of the Cleveland law under which the city is now being governed was filed in the supreme court this afternoon.

“It is a quo warranto suit styled the State of Ohio, ex rel Attorney General vs. M. W. Beacom and the other members of the board of control, otherwise known as Mayor Johnson's cabinet. It is based upon the contention that the act of May 16, 1891, applies only to the city of Cleveland and is therefore special legislation.”