My Story (30 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

The Cleveland

Leader

sent for Homer Davenport, the celebrated cartoonist, and for weeks his cartoons appeared daily in that paper. Davenport's wonderful drawings had been a large factor in defeating the Cox crowd in Cincinnati at a previous election, and in other cities his services had been found invaluable in similar contests. Davenport hadn't much heart for his task. He came to see me and explained the nature of his connection with the

Leader

â as I remember it, his time was sold to the

Leader

by an Eastern paper to which he was under contract. At any rate he appeared greatly relieved when I told him that I appreciated his position and wouldn't bear him any personal grudge. “Go ahead and do your best for the

Leader

,” I said to him, “I'll forgive you.” “Well, my father never will,” he answered, “I don't know how I am going to square this with him.” His father like himself had for years been a single taxer.

And so the fight went on. The Republicans were sure they were going to win. They had all the money they wanted and they brought out brass bands and worked all the old-fashioned mechanical effects for all they were worth. Everything of this description had long been eliminated from our campaigns. They neglected no possible point of vantage in their efforts to influence people against our side and succeeded so well that it amounted almost to public disgrace for a business man to admit that he was for me. Everything that offered the slightest chance for attack was attacked. Cruel and malicious stories were circulated about Mr. Cooley's administration of his department. As fast as the enemy launched one of these unspeakable falsehoods we set about running it down.

Never before or since was the contest as bitter as in that campaign. But it had its humorous aspects too. Each campaign had its own particular slogan or catch phrase. In my first race for mayor my opponent W. J. Akers made frequent reference in his speeches to picking strawberries in Newburg when he was a boy. Harvey D. Goulder who ran against me in the second campaign spoke with feeling of the old town pump. William H. Boyd had something to say of “forging thunderbolts” to my undoing. And so in their turn we had rung the changes on picking strawberries in Newburg, on drinking at the old town pump, and on the forging of thunderbolts, but Mr. Burton furnished us with the most delightful phrase of all. In accepting his nomination he declared in classic Latin, “Jacta est alae,” for Mr. Burton is a scholar. This expression, unfortunately for him, sent the man on the street into convulsions of mirth. One or two of our speakers paraphrased it in German and French, and I interpreted it for the Irish as “Let 'er go Gallagher.”

Then Mr. Burton had an impressive way of beginning a speech by saying,

“I have spoken within the halls of Parliament in London, and in the Crystal Palace also in London, in Berlin, Germany, and with what poor French I could command in the south of France, in Brest, and once my voice was heard within the confines of the Arctic Circle, in the valley of the Yukon, Alaska, but kind friends, I am glad to be here with you to-night.”

On the heels of this address Peter Witt arose in one of our tents and began his nightly speech with great solemnity,

“I have spoken in the corn fields of Ashtabula, in the stone quarries of Berea and at the town hall in Chardon, etc., etc.”

There had been fifty-five injunctions against the low-fare companies now. Three times I had been elected on the same platform. The people had shown clearly by their votes that they wanted what we were standing for and the fifty-five injunctions indicated how hard the Cleveland Electric and its allied interests had tried to thwart their will. Would the people give up the fight now? Would they be fooled by Privilege?

I was elected by a majority of nine thousand while the city solicitor and the members of the board of public service were returned by majorities of several thousand more. It was a tremendous vindication coming as it did at the close of such a campaign. The east end, the rich and aristocratic section of the city voted solidly against me but contributed somewhat no doubt to the majorities of the candidates who ran ahead of me.

The newspapers were all agreed that the election was one of the most orderly ever held in Cleveland. That night the streets were a surging mass of humanity. The whole town seemed to be out. While some thousands were receiving election returns in the Armory and in the theaters, tens of thousands were swarming on the streets. They overflowed the sidewalks and spread out over the streets in such numbers that the street cars had to crawl at snail's pace in the down town region, and automobiles had difficulty in getting through at all. It was unmistakably a great common people's victory. The City Hall was packed with a happy, radiant crowd and Peter

Witt gave characteristic expression to his exuberance of spirit in a telegram to President Roosevelt reading, “Cleveland as usual went moral again. The next time you tell Theodore to run tell him which way.”

Poor Mr. Burton! He must have been sadly disillusioned and deeply wounded. He had nothing to say. He hurried off to Washington or somewhere without sending me the congratulatory message which is customary on such occasions.

On election night when the returns began to show beyond doubt that Burton was defeated the Concon issued orders to stop selling seven tickets for a quarter (this rate of fare having been in operation from October 2 to November 5), and go back to the old rate of a five-cent cash fare or eleven tickets for fifty cents.

LAST DAYS OF THE FIGHT

T

HE

election occurred November fifth. On the seventh I sent the following letter to the Cleveland Electric Railway Company:

“

GENTLEMEN:

The passage of various ordinances by the council within the past few months, and the legislation necessary to complete some of the grants already made, indicate that the council will, in the near future, be called upon to consider matters affecting the general street railroad situation. The approaching expiration of the franchises upon many of the lines operated by your company of course requires early action to provide for an uninterrupted continuance of public service.

These considerations lead me to suggest that I call a public meeting of the present members of the council and the council-men-elect to consider any suggestions your company may have to offer either to insure against confusion or public inconvenience at the date of your franchise expirations, or looking to a general settlement of the entire street railroad question. I shall be very glad to call such a meeting for the council chamber at ten o'clock Saturday morning, unless you prefer a later date, in which case I shall be glad to know your preference at as early an hour to-morrow as is convenient, so that the persons who would attend such conference may be informed in time.

I am assured by members of the council, and I speak for them and the city administration, in saying that we have a common desire to bring about a settlement of this question which will be

just and equitable to your company and upon terms that will preserve fully the public right.

T

OM

L. J

OHNSON,

Mayor

.”

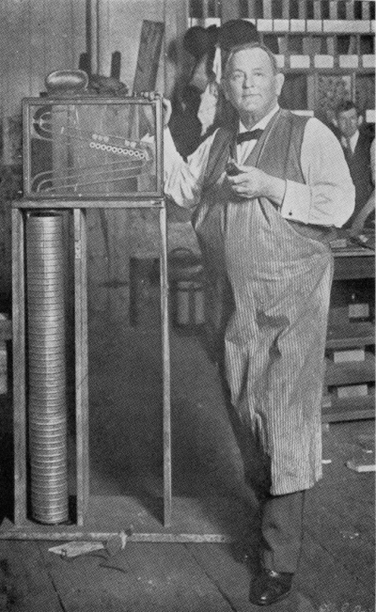

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

At work on Pay Enter Fare Box

President Andrews accepted in behalf of his company and once more we embarked on peace negotiations. Little was done at the Saturday meeting but the Concon announced it would bring a proposition to council on the following Thursday. It did â a proposition to make a six months' trial of three-cent fare

after a twenty-five year franchise had been granted

. The council rejected this proposition and tried in vain at this and future meetings to have Mr. Andrews name a price at which his company would lease its property on the holding company plan.

During the election Concon stock had dropped to forty-two, and later to thirty-seven, and by the middle of November to thirty-three dollars a share. Yet the company instead of meeting council in a conciliatory spirit at first exhibited all its old time obstinacy and a good deal of its old time arrogance. Realizing at last that the city had no intention of giving up, the Concon selected F. H. Goff, a prominent attorney as well as a good business man, a man of sterling qualities and one who inspired confidence, as its representative, to arrange the details of a settlement. At the conclusion of the negotiations these characteristics of Mr. Goff were generally understood and appreciated by the public. He began by refusing all compensation for his work, and a lawyer of his standing would have charged a private client a fortune for such service.

The council appointed me to act in a similar capacity

for the city. So the administration and the council were finally put in the position for the first time of dealing with a single individual with power to act, and whose decisions the Cleveland Electric was bound to accept. Lawyers representing both sides of the contest were appointed to determine the exact date of the expiration of all unexpired franchises, engineers to appraise trackage and pavement claims, operating managers to get at the valuation of cars, rolling stock and miscellaneous equipment, and so on through the various classifications of the property. All valuations were made by a committee of two persons, and when they failed to agree Mr. Goff and myself were the arbitrators. The principal points to be agreed upon were physical and franchise values of the property, and that the management should be in the hands of a holding company which should manage the street railroad for the benefit of the car riders.

For four months the negotiations between Mr. Goff and the mayor were carried on in public meetings held almost daily in the council chamber. At the end of that time Mr. Goff recommended a valuation of sixty-five dollars per share on Cleveland Electric stock and I recommended a valuation of fifty dollars per share.

At about the close of these negotiations the State legislature passed the Schmidt bill which provides that property owners' consents are no longer needed for a new street railway franchise on a street where there is already a street car line; that new franchises may be given on such streets within one year after street car service has been abandoned or within two years prior to the expiration of a franchise; that if fifteen per cent, of the voters petition for an election within thirty days after the passage

of a franchise ordinance, there must be an election, and the ordinance becomes invalid if a majority of the votes cast are against it.

If this law had been on the statutes when the Cleveland Electric's franchises expired on Central and Quincy avenues, it would have been impossible for the Concon to prevent the establishment of three-cent car service on those streets through the medium of a consent war.

Under the Schmidt law the council was enabled to grant to the Forest City Company certain franchises without property owners' consents, and it also made a grant to the Neutral Street Railway (another low fare company) for lines on Central and Quincy avenues.

Two or three weeks previous to this the stockholders of the Forest City had had their first meeting and I had been present by invitation, and had strongly advised them to consent to a consolidation with the Cleveland Electric under the name of the Cleveland Railway Company. I told them that in my opinion their company had served its purpose, that it had been organized to get lower fares for the people of Cleveland which was now practically accomplished, that the necessity for competition had passed and that the city's needs would be best served by one company.

Mr. Goff agreed to the holding company plan and he and I soon got together on a price of fifty-five dollars a share for the stock. Council made a security grant to the old company which was to become operative as a grant only in case the holding company failed to pay the stockholders six per cent. on the agreed value, and which gave the city the option of buying the stock at one hundred and ten dollars at any time. That the fare was to

be three cents on the whole united system goes without saying.

On April 27, 1908, the Municipal Traction Company, the holding company, took charge of the lines, and inaugurated its operations by running the cars free for that one day. This free day was meant to serve as an object lesson of their victory to the people. Nothing like this had been done in any large city before â nor perhaps any place else except in Johnstown after the flood. It was like a holiday. Men and women and children rode and in spite of the crowds not a single accident happened to mar the happiness of the day.

Threefer employés were getting a cent an hour more than Concon employés so the wages of the latter were immediately raised one cent per hour, and all the men were provided with free uniforms. This made the maximum pay twenty-five cents per hour. Some of the old company's men showed a spirit of disloyalty and insubordination immediately the Municipal Traction Company commenced its operations, and a strike was early threatened. The labor union of Concon employés had, it seems, a contract with the old company which promised a wage increase of two cents an hour providing the Concon got a renewal of its franchise. The low-fare employés were also unionized, but their charter was revoked by the international body on the ground that some of them were stockholders in the company that employed them. The charter was revoked without notice to the low-fare company which had a contract with the union. Mr. du Pont declared the entire willingness of the Municipal Traction Company to arbitrate all differences and neither he nor I believed that a strike would be called,

but on May 16 a strike was called. It affected the members of the old company's labor union only. The questions raised were:

1. Whether the agreement between the Municipal and the old Forest City union had any bearing on the agreement between the Cleveland Electric and the striking union.

2. Whether the international association had the right to revoke the charter of a local which had an agreement with the railway company without the company's consent.

3. Was the two-cent-an-hour agreement between the Cleveland Electric and the union binding on the Municipal as lessee of the Cleveland Electric?

Violence broke out at the very outset of the strike, cars were stoned, wires cut and dynamite placed on the tracks. The strike with its accompanying necessity of operating the cars with inexperienced men, and the expense occasioned by the destruction of property was just one of the things resorted to to make the operations of the holding company fail. Unfriendly newspapers abused the service, political organizations were formed to refuse to pay fares by giving conductors more work than they could do, these same men organized clubs to tender large bills in payment of fares in order to exhaust the conductors' change. It wasn't men with dinner-pails who offered five dollar bills in payment of three-cent fare, nor was it groups of labor unionists who crowded the cars at certain points and exerted themselves to make it impossible for conductors to collect fares, and it wasn't workingmen either who instigated conductors to overlook fares or persistently to refuse to collect them. But all these things were done â these and many more â by

some of the people who were pledged to carry out the agreement which Mr. Goff had made in their behalf.

In spite of all past experiences with the Concon, we were unprepared for these attacks. We thought a gentleman's agreement meant a gentleman's agreement. We were mistaken.

The Municipal Traction Company, on the other hand, was not free from blame. Some bad moves must be charged to its account, but it can never truthfully be said that it dishonestly violated any agreement or maliciously refused to abide by its contracts. Its mistakes were those of judgment.

The strike finally died by reason of the weakness of its own case. It did not have the support of the labor unions of the city and strikes instigated and aided by Privilege are never very useful to the strikers themselves nor to the cause of labor.

Of course I was blamed for everything. If the cars were too cold it was my fault, if they were too hot it was my fault. If the rails were slippery or a trolley pole broke it was my fault. If the cars were late, if they stopped on the wrong corners, if they were held up at railroad crossings, if a conductor couldn't change a twenty-dollar bill it was my fault. It is even said that a man who fell off a car one night exclaimed as he went sprawling on the pavement, “Damn Tom Johnson.”

Finally a referendum petition was circulated just in time to become operative before the end of the thirty-day period following the making of the grant. Republican organizations, business men's organizations and all the combinations that Privilege could bring to bear were enlisted against this grant. At the referendum election,

October 22, 1908, the grant was defeated by 605 votes out of the 75,893 votes cast. The people, in my opinion, made their biggest blunder in defeating this franchise. If they had been even half as patient with the Municipal Traction Company as they had been with the Concon all would have been well. The defects in the service of which they complained, and often justly, would have been remedied. But, as I have already pointed out the people insist on a higher degree of efficiency in a public company than they do in a private one.

There was a touch of the irony of fate in the defeat of the franchise. That the referendum should be invoked by the very interests which had always opposed it, and that the result of the first election under the law should be inimical to the people's movement was something of a blow. But people learn by their mistakes and the good effects that have come and will come from the referendum will largely outweigh any temporary disadvantages.

One stipulation of the agreement between Mr. Goff and myself was that should our plans fail the property which had passed into the hands of the Cleveland Railway Company should be restored to the original owners, that is that the old company should take back the Cleveland Electric property and that the original three-cent lines should be returned to the Forest City. The old company refused to comply with this agreement. Instead it sought by every means to embarrass the Municipal Traction Company, urging creditors to press claims, tying up the funds of the Municipal in court and finally succeeding in having receivers appointed, though the money tied up was more than sufficient to meet all obligations that

were then due. The receivers took over all the street railroads in the city and under the direction of Judge Tayler who appointed them they operated the property from November 13, 1908, to March 1, 1910.