My Story (9 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

Lest some reader of the foregoing paragraphs think I condemn the motives which prompt charity let me disclaim that! It is not generous impulses, not charity itself, to which I object. What I do deplore is the short-sight

edness which keeps us forever tinkering at a defective spigot when the bung-hole is wide open. If we were wise enough to seek and find the causes that call for charity there would be some hope for us.

In Johnstown it was a defective dam used for the recreation of the well-to-do. A great reservoir of water in which fish were kept to be fished for by the privileged members of the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club of Pittsburgh. This property, comprising some five hundred acres, had been acquired by purchase. Originally a part of the State canal system it had passed into the hands of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company when the latter purchased the canal in 1857â58, and became private property in 1875 when Congressman John Reilly bought it. He later offered it for sale at two thousand dollars, when it was purchased by the originator of the Club above mentioned and two other Pittsburgh gentlemen.

It was suspected that the dam wasn't safe. I myself had gone to look at it one day the summer before it broke and had speculated on what might happen to us in the little city eight miles down the valley in case the dam should give way. The innocent cause of the catastrophe when at last it did come was some leaves which clogged the spill-way. Citizens living in the vicinity wanted to remove the wire grating which held the leaves back and caused the water to go over the breast of the dam, but were refused permission to do so, refused, forsooth, because some of the privately-owned fishes swimming around in the privately-controlled pool might escape â might be swept over the confines of their aristocratic dwelling and eventually be caught with a bent pin attached to a cane pole, instead of being hauled out of the sacred waters, in

which they had been spawned, by that work of art known as a high class rod and reel equipped with a silk line and a many-hued artificial fly.

Yes, the Johnstown flood was caused by Special Privilege, and it is not less true that Special Privilege makes charity apparently necessary than it is that “crime and punishment grow on one stem!” It is cupidity which creates unjust social conditions sometimes for mere pleasure â as in this case â but generally for profit. The need of charity is almost always the result of the evils produced by man's greed.

What did charity do for Johnstown? It was powerless to restore children to parents, to reunite families, to mitigate mourning, to heal broken hearts, to bring back lost lives. It had to be diverted to uses for which it was not intended.

As charity

it had to be eliminated, as we have seen, before the people could save themselves.

Materially Johnstown was benefited by the flood, just as so many other communities have been by similar catastrophes. And material prosperity seems so important that we have acquired a habit of saying, “Oh, the fire was a good thing for Chicago or London,” “The flood was a good thing for Johnstown,” etc., etc. But is it not true that when human lives are lost the price paid for material benefits is one that can't be counted? We must leave this out of the reckoning then when we say that the flood was a good thing for Johnstown.

The town went forward as one united people now no longer divided by separate borough governments, and on the wreckage of the former city built up a great manufacturing community which to-day numbers more than fifty thousand souls.

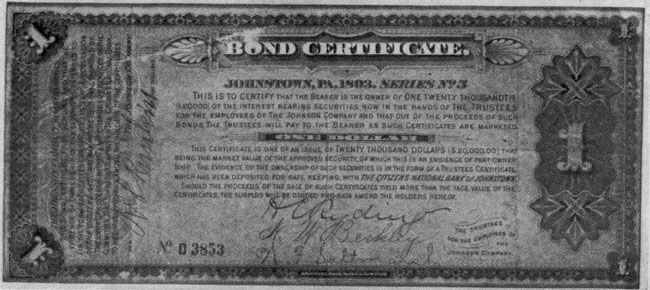

CERTIFICATE ISSUED BY THE JOHNSON COMPANY AT JOHNSTOWN

It was a marvelous thing to witness such utter destruction and in so short a time such complete reconstruction, and the spectacle made a profound impression upon me. When I became mayor of Cleveland twelve years later I was faced by problems of a different character, but problems due to the same root cause from which Johnstown's difficulties came. And many, many times when these problems seemed hopelessly entangled I reasoned with myself that there must be a way out, since in Johnstown under apparently greater disadvantages we had always found a way.

In Cleveland we made progress by slow and painful degrees. No completed picture presented itself here as in Johnstown, but, leaving out the element of time, the cases were, to my mind, so similar as almost to parallel each other.

The problems which had to be met in Johnstown and which are being met in Cleveland have their counterparts in all other communities, and sooner or later will present themselves for solution. Just as surely as we meet these problems with remedial measures only, with charitable acts and time-serving expedients,â just so surely will great catastrophes in some form or other overtake us.

If we will seek out and remove the social wrong which is at the bottom of every social problem, the problem will vanish. Nothing could be simpler. If, on the other hand, the cause is not eradicated the problem will persist, multiply itself and all the evils that go with it, until one day that particular catastrophe which goes under the dreadful name â

revolution

â occurs.

It was at our Johnstown plant during the panic of the early nineties that we hit upon a device for supplying the

shortage of currency which has since been so widely used in times of similar stress. There were plenty of orders for our product â street railroad rails â but the buyers couldn't pay cash. We called our employes together and explained the situation to them. We told them we were unable to command enough currency to pay the full amount of their wages, but that if they were willing to accept a small percentage in cash and the remainder in certificates that we should be able to continue to operate the mill; if they could not agree to such an arrangement we should have to shut down.

The law specifically prohibited the payment of wages in anything but money â a provision intended to protect working men from exploitation by “the company store,” an institution we never had in connection with any of our industries. To avoid violating the law therefore we should have to hand over to each employe his full pay in currency with the understanding that he was to present himself immediately at another window in the office and buy an agreed upon percentage of certificates.

We were selling rails for such cash payments as we could get and accepting the purchasers' bonds for the remainder. We were proposing to do for our men just what our customers were doing for us. The bonds were to be held by a joint committee of company representatives and working men and against these bonds the certificates were issued. Our employes decided to accept our proposition, and our cooperative enterprise, for that is what it was, proved entirely satisfactory. The certificates passed at nearly par and we experienced no serious legal embarrassment, nor was there any misunderstanding of our motives.

In a way these certificates corresponded to clearing house certificates, at that time forbidden by law, but since partially legalized â which is to say that certain national banks now have legal authority to issue clearing house certificates. It's curious that what is right and lawful for some banks is wrong and unlawful for others. But necessity knows a law that isn't written on statute books and will continue to force the use of clearing house certificates or similar expedients from time to time until we are wise enough to arrange our money-issuing machinery with a view to taking care of business in hard times as well as in good times.

*

HENRY GEORGE, THE MAN AND HIS BOOKS

M

Y

interest in Privilege, as this record has shown, was all on the privileged side. The unwisdom of the public in making grants of the highway, or the question of municipal ownership would have been as incomprehensible to me as the Greek alphabet. I had acquired my various special privileges by perfectly legitimate methods according to my own standards. Most of my street railway operations were based upon franchises already in existence which I had purchased from the owners. Very few of my grants had come through city ordinances passed for my benefit. I had had comparatively little contact with politics in any way. I had sometimes contributed to the campaign funds of both political parties and was therefore indifferent as to which side won. I was absolutely interested in business, in the great business opportunities before me, in the sure prospect of continuing to make money,â and I was looking for a conductor all the time. I knew now that there were many guises in which he might appear, and my training had fitted me to recognize him in almost any of them.

When I was securely established as a business man, and at the very height of my money-making career the incident which was to change my whole outlook on the universe occurred. It came about through the intervention of a conductor too â but not the kind I was looking for â just

a prosaic railroad train conductor running between Cleveland and Indianapolis.

I still owned my Indianapolis interests and was traveling between that city and Cleveland frequently. When on one of these trips a train boy offered me a book called

Social Problems

. The title led me to think it dealt with the social evil, and I said as much, adding that the subject didn't appeal to me at all. Overhearing my remarks, the conductor urged me to buy the book, saying that he was sure it would interest me, and that if it didn't he would refund the half dollar I invested in it. So I bought it, and I read it almost without stopping. Then I hastened to get all the other books which Henry George had written up to that time. I read

Progress and Poverty

next. It sounded true â all of it. I didn't want to believe it though, so I took it to my lawyer in Cleveland, L. A. Russell, and said to him:

“You made a free trader of me; now I want you to read this book and point out its errors to me and save me from becoming an advocate of the system of taxation it describes.”

The next time I went to Johnstown I talked with Mr. Moxham about it. He said he would read it. For months it was the chief subject of conversation between these two men and myself. Mr. Moxham read it once, carefully marking all the places where, in his opinion, the author had departed from logic and indulged in sophistry. He wasn't willing to talk much about it, however, saying he wanted time to think it over and read it once more before he discussed it with anybody. By and by he said to me,

“I've read

Progress and Poverty

again and I have had

to erase a good many of my marks, but I don't want to talk about it yet.”

And then in due course of time there came a day when he said,

“Tom, I've read that book for the third time and I have rubbed out every damn mark.”

Long before this I had become convinced that Mr. George had found a great truth and a practical solution for the most vexing of social problems, but Mr. Russell wasn't yet ready to admit it. Some time later he and Mr. Moxham and I were obliged to go to New York together on business, and we spent our evenings in my room at the hotel smoking and discussing

Progress and Poverty

. Mr. Russell's avowed intention was “to demolish this will-o'-the-wisp.” Every time he stated an objection either Mr. Moxham or I would hold him up to explain exactly what he meant by such terms as land, labor, capital, wealth, etc. As fast as he correctly defined their meanings his objections vanished one by one, and that trip worked his complete conversion and was brought about by his own reasoning, and not by our arguments. The effect of all of this upon me was to make every chapter of that book almost as familiar to me as one of my own mechanical inventions.

It was in 1883 that I became interested in Mr. George's teachings â the year my family took up their residence in Cleveland, though previous to this time my wife and our two children, a son and a daughter, both of whom were born in Indianapolis, had spent some time with me at the Weddell House, where I lived when I was in the city.

I continued in my business with as much zest as ever, but my point of view was no longer that of a man whose chief object in life is to get rich. I wanted to know more about Mr. George's doctrines. I wanted to ask him questions, for I had not outgrown the why, what and wherefore habit of my childish days.

My business took me often to New York and on one of those trips in 1885 I went to call upon Mr. George at his home in Brooklyn. I was much affected by that visit. I had come to a realizing sense of the greatness of the truth that he was promulgating by the strenuous, intellectual processes which have been described, but the greatness of the man himself was something I felt when I came into his presence.

Before I was really aware of it I had told him the story of my life, and I wound up by saying:

“I can't write and I can't speak, but I can make money. Can a man help who can just make money?”

He assured me that money could be used in many helpful ways to promote the cause, but said that I couldn't tell whether I could speak or write until I had tried; that it was quite probable that the same qualities which had made me successful in business would make me successful in a broader field. He evidently preferred to talk about these possibilities to dwelling on my talent for money-making. He suggested that I go into politics. This seemed quite without the range of the possible to me, and I put it aside, but said that I would go ahead and make money and devote the profits largely to helping spread his doctrines if he would let me.

One of the first things I did, and it makes me smile to

recall it, was to purchase several hundred copies of Mr. George's new book,

Protection or Free Trade

, and send one to every minister and lawyer in Cleveland.

Why do converts to social ideals always select these most unlikely of all professions in the world as objects for conversion in their campaigns in behalf of new ideas?

I had not yet discovered that it is “the unlearned who are ever the first to seize and comprehend through the heart's logic the newest and most daring truths.”

That first meeting with Mr. George was the beginning of a friendship which grew stronger with each passing day and which, it seemed to me, had reached the full flower of perfection when I stood at his bedside in the Union Square Hotel in New York City the night of October 28, 1897, and saw his tired eyes close in their last sleep.

Mr. George was about forty-six years old, I thirty-one, when we met and from the very first our relations were those of teacher and pupil.

My first participation in any organized activity was to attend a meeting of a voluntary committee called at the home of Dr. Henna in New York in August, 1886, to consider how our question could be made a political one. Among that little group besides Mr. George and Dr. Henna, were Father McGlynn, William McCabe, Louis F. Post and Daniel DeLeon. A short time afterwards a second meeting was held at Father McGlynn's rectory, but before we had formulated any specific plans Mr. George was called upon to become the candidate of the labor unions of New York for mayor, and so without our volition our object was accomplished. I was active in this campaign as also in the state campaign the following

year, when, against his judgment, Mr. George was put forward as the United Labor Party candidate for secretary of State.

Mr. George persisted in his belief that my greatest service to the cause lay in the political field, and every time I urged my inability to speak as a reason against this, he answered that I couldn't tell because I had not tried.

And so one night early in the year 1888 I tried, the occasion being a mass meeting in Cooper Union. Of this attempt Louis F. Post generously wrote some years later, “He spoke for possibly five minutes, timidly and crudely but with evident sincerity, and probably could not have spoken ten minutes more had his life been the forfeit,” but his private assurance to me was that it was without exception the worst speech he had ever heard in all his days. I am sure he has never heard anything to match it since. I know I never have.

But this unpromising beginning didn't discourage Mr. George and it made the next trial a little easier for me; and by and by I was speaking with him at various public meetings. I recall one especially large and successful one in Philadelphia.

Some five or six years later, perhaps, in a great meeting in Chickering Hall, New York, my part on the programme was to answer any questions which might be put by the audience. This was usually done by Mr. George, and though I had tried my hand at it several times before this was the first time I had attempted it when Mr. George was present. When the meeting was over we left the hall together and walked some blocks before a word was spoken. I had gotten on very well in my own estimation, but Mr. George's continued silence was raising doubts in

my mind. When he did speak, he laid his hand on my arm and said,

“I am ready to go now. There is someone else to answer the questions.”

With Mr. George and Thomas G. Shearman of New York, I went before the Ohio legislature and advocated a change in the tax laws.

In the winter of 1895â96 a newspaper called the

Recorder

was started in Cleveland. At Mr. George's suggestion Louis F. Post, then of New York, came to Cleveland and went onto the paper as an editorial writer. Hoping that the

Recorder

might prove a truly democratic organ and thinking it might become self-supporting if it did not have too hard a struggle at the start, I, voluntarily, at first without Mr. Post's knowledge, and later, against his advice, made good the weekly deficits. First and last I contributed eighty thousand dollars to this enterprise. Regarding this purely as one of my contributions to our cause I took no evidence either of debt or ownership consideration. An effort to throw the paper against Mr. Bryan was prevented by Mr. Post. In 1897 I was pretty badly hit by the panic and had to withdraw my financial assistance with only a week's warning. Mr. Post left the

Recorder

at about this time and the paper was obliged to abandon the regular newspaper field, though it continued as a kind of court calendar.

In the readjustment I was compelled to pay an additional twenty thousand dollars, the courts maintaining that I was a stockholder. I did not mind having put in the eighty thousand, but I always considered the enforced payment of that additional twenty thousand a great injustice.

Subsequently Mr. Post established

The Public

in Chicago.

To this truly democratic weekly journal it has been my privilege to give some support.

In such ways as these I was helping Mr. George's cause and it was my ambition to become able to do all the outside work, the rough and tumble tasks, leaving him free and undisturbed in his most useful and enduring field of influence, that of writing. It was my privilege to be partly instrumental in making it possible for him to write his last book â a privilege for which I shall never cease to be profoundly grateful.

A warm friendship sprang up between my father and Mr. George and the latter built a house at Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn, next to my father's and my brother Albert's and very near the summer home of my family at the same place. Together my father and Mr. George selected family burial lots adjoining each other in Greenwood Cemetery and overlooking the ocean. Here as time goes on members of our respective families are gathered to their final rest.

I was with Mr. George a great deal in the Fort Hamilton days when his home was the headquarters of the single tax movement in this country. Sometimes he went with me on bicycling excursions, and we used to laugh a good deal about one business trip he made with me. I invited him to go, telling him that I should not be very busy, that we could take our wheels and have some time to visit. It was a western trip. We stopped at a good many towns, I had interviews with several men in each place and, as was my custom, I made no discrimination between night and day when it came to settling business matters, or taking trains. To me it was rather a leisurely journey. We got in a few spins on our bicycles and of course we visited

on the train. Mr. George said nothing to me about the character of the trip, but when he got home his comment to Mrs. George was,

“Well, if Tom calls this trip one when he wasn't very busy, he needn't invite me to go on one when he is.”

In Mr. George's last campaign for mayor of New York in 1897 I was his political manager. It was during that campaign that I was hissed in a public meeting, the first and only time in my life that that ever happened to me. It was at a meeting in Brooklyn in a large hall or an opera house. As I stepped forward to the middle of the stage to begin my speech a slight hissing came from the house, but it was overbalanced by the applause. A few moments later when I had gotten fairly started it came again, this time loud and insistent and from a group of men seated in the front and near the center of the balcony. I stopped, looked towards them and called out, “Well, what is it? What don't you like? Tell me; maybe I can explain.” No answer, but more hisses.

“Oh, you don't know what you are hissing for? You were just told to do it,” I continued. “Well, come on, give us some more of it. I like it, it makes me feel good,” and I coaxed for more hissing, making the sound of the tongue against the teeth used to urge a horse to greater speed. But I got no response now and the meeting was not disturbed again.

The group of hissers had evidently been sent to the meeting with instructions to break it up, but their courage failed them. When the meeting was over they followed me out and while I was waiting for the private trolley car in which I was traveling that night, a great husky workman standing near me on the sidewalk exclaimed in loud tones, “Well,

did you see the big ââ ââ ââ throw the con into them!”