Natasha's Dance (26 page)

Prince Volkonsky was in Nice when he heard the news of the decree. That evening he attended a thanksgiving service at the Russian church. At the sound of the choir he broke down into tears. It was, he said later, the ‘happiest moment of my life’.

186

186

Volkonsky died in 1865 - two years after Maria. His health, weakened in exile, was broken by her death, but right to the end his spirit was intact. During these last months he wrote his memoirs. He died, pen in hand, in the middle of a sentence where he started to recount that vital moment after his arrest when he was interrogated by the Tsar: ‘The Emperor said to me: “I…”.’

Towards the end of his memoirs Volkonsky wrote a sentence which the censors cut from the first edition (not published until 1903). It could have served as his epitaph: ‘The path I chose led me to Siberia, to exile from my homeland for thirty years, but my convictions have not changed, and I would do the same again.’

187

187

3

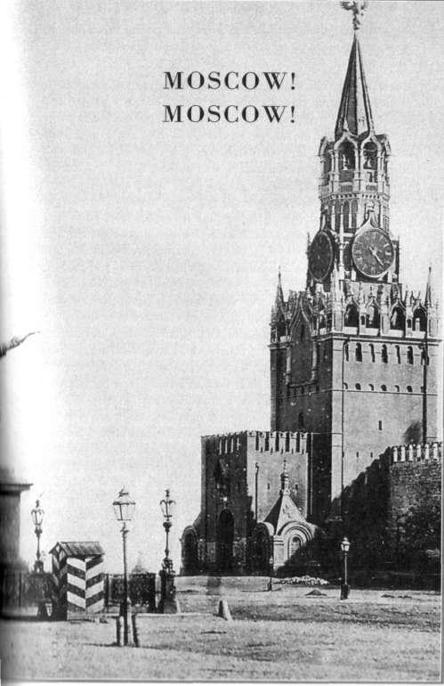

overleaf:

St Basil’s Cathedral, Red Square, Moscow,

during the late nineteenth century

1

’There it is at last, this famous town,’ Napoleon remarked as he surveyed Moscow from the Sparrow Hills. The city’s palaces and golden cupolas, sparkling in the sun, were spread out spaciously across the plain, and on the far side he could just make out a long black column of people coiling out of the distant gates. ‘Are they abandoning all this?’ the Emperor exclaimed. ‘It isn’t possible!’

1

1

The French found Moscow empty, like a ‘dying queenless hive’.

2

The mass exodus had begun in August, when news of the defeat at Smolensk had arrived in Moscow, and it reached fever pitch after Borodino, when Kutuzov fell back to the outskirts of the city and finally decided to abandon it. The rich (like the Rostovs in

War and Peace)

packed up their belongings and left by horse and cart for their country houses. The poor walked, carrying their children, their chickens crated on to carts, their cows following behind. One witness recalled that the roads as far as Riazan were blocked by refugees.

3

2

The mass exodus had begun in August, when news of the defeat at Smolensk had arrived in Moscow, and it reached fever pitch after Borodino, when Kutuzov fell back to the outskirts of the city and finally decided to abandon it. The rich (like the Rostovs in

War and Peace)

packed up their belongings and left by horse and cart for their country houses. The poor walked, carrying their children, their chickens crated on to carts, their cows following behind. One witness recalled that the roads as far as Riazan were blocked by refugees.

3

As Napoleon took up residence in the Kremlin palace, incendiaries set fire to the trading stalls by its eastern wall. The fires had been ordered by Count Rostopchin, the city’s governor, as an act of sacrifice to rob the French of supplies and force them to retreat. Soon the whole of Moscow was engulfed in flames. The novelist Stendhal (serving in the Quartermaster’s section of Napoleon’s staff) described it as a ‘pyramid of copper coloured smoke’ whose ‘base is on the earth and whose spire rises towards the heavens’. By the third day, the Kremlin was surrounded by the flames, and Napoleon was forced to flee. He fought his way ‘through a wall of fire’, according to Segur, ‘to the crash of collapsing floors and ceilings, falling rafters and melting iron roofs’. All the time he expressed his outrage, and his admiration, at the Russian sacrifice. ‘What a people! They are Scythians! What resoluteness! The barbarians!’

4

By the time the fires were burnt out, on 20 September 1812, four-fifths of the city had been destroyed. Re-entering Moscow, Segur ‘found only a few scattered houses standing in the midst of the ruins’.

4

By the time the fires were burnt out, on 20 September 1812, four-fifths of the city had been destroyed. Re-entering Moscow, Segur ‘found only a few scattered houses standing in the midst of the ruins’.

This stricken giant, scorched and blackened, exhaled a horrible stench. Heaps of ashes and an occasional section of a wall or a broken column alone indicated

the existence of streets. In the poorer quarters scattered groups of men and women, their clothes almost burnt off them, were wandering around like ghosts.

5

5

All the city’s churches and palaces were looted, if not already burned. Libraries and other national treasures were lost to the flames. In a fit of anger Napoleon instructed that the Kremlin be mined as an act of retribution for the fires that had robbed him of his greatest victory. The Arsenal was blown up and part of the medieval walls were destroyed. But the Kremlin churches all survived. Three weeks later, the first snow fell. Winter had come early and unexpectedly. Unable to survive without supplies in the ruined city, the French were forced to retreat.

Tolstoy wrote in

War and Peace

that every Russian felt Moscow to be a mother. There was a sense in which it was the nation’s ‘home’, even for members of the most Europeanized elite of Petersburg. Moscow was a symbol of the old Russia, the place where ancient Russian customs were preserved. Its history went back to the twelfth century, when Prince Dolgoruky of Suzdal built a rough log fortress on the site of the Kremlin. At that time Kiev was the capital of Christian Rus’. But the Mongol occupation of the next two centuries crushed the Kievan states, leaving Moscow’s princes to consolidate their wealth and power by collaboration with the khans. Moscow’s rise was symbolized by the building of the Kremlin, which took shape in the fourteenth century, as impressive palaces and white-stoned cathedrals with golden onion domes began to appear within the fortress walls. Eventually, as the khanates weakened, Moscow led the nation’s liberation, starting with the battle of Kulikovo Field against the Golden Horde in 1380 and ending in the defeat of the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan in the 1550s, when it finally emerged as the capital of Russia’s cultural life.

War and Peace

that every Russian felt Moscow to be a mother. There was a sense in which it was the nation’s ‘home’, even for members of the most Europeanized elite of Petersburg. Moscow was a symbol of the old Russia, the place where ancient Russian customs were preserved. Its history went back to the twelfth century, when Prince Dolgoruky of Suzdal built a rough log fortress on the site of the Kremlin. At that time Kiev was the capital of Christian Rus’. But the Mongol occupation of the next two centuries crushed the Kievan states, leaving Moscow’s princes to consolidate their wealth and power by collaboration with the khans. Moscow’s rise was symbolized by the building of the Kremlin, which took shape in the fourteenth century, as impressive palaces and white-stoned cathedrals with golden onion domes began to appear within the fortress walls. Eventually, as the khanates weakened, Moscow led the nation’s liberation, starting with the battle of Kulikovo Field against the Golden Horde in 1380 and ending in the defeat of the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan in the 1550s, when it finally emerged as the capital of Russia’s cultural life.

To mark that final victory Ivan IV (‘the Terrible’) ordered the construction of a new cathedral on Red Square. St Basil’s symbolized the triumphant restoration of the Orthodox traditions of Byzantium. Originally named the Intercession of the Virgin (to mark the fact that the Tatar capital of Kazan had been captured on that sacred feast day in 1552), the cathedral signalled Moscow’s role as the capital of a

religious crusade against the Tatar nomads of the steppe. This Imperial mission was set out in the doctrine of Moscow as the Third Rome, a doctrine which St Basil’s set in stone. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moscow saw itself as the last surviving centre of the Orthodox religion, as the heir to Rome and Byzantium, and as such the saviour of mankind. Moscow’s princes claimed the imperial title ‘Tsar’ (a Russian derivation of ‘Caesar’); they added the double-headed eagle of the Byzantine emperors to the figure of St George on their coat of arms. The backing of the Church was fundamental to Moscow’s emergence as the mother city of Holy Rus’. In 1326 the Metropolitan had moved the centre of the Russian Church from Vladimir to Moscow and, from that point on, Moscow’s enemies were branded the enemies of Christ. The union of Moscow and Orthodoxy was cemented in the churches and the monasteries, with their icons and their frescoes, which remain the glory of medieval Russian art. According to folklore, Moscow boasted ‘forty times forty’ churches. The actual number was a little over 200 (until the fires of 1812), but Napoleon, it seems, was sufficiently impressed by his hilltop view of the city’s golden domes to repeat the mythic figure in a letter to the Empress Josephine.

By razing the medieval city to the ground, the fires carried out what Russia’s eighteenth-century rulers always hoped for. Peter the Great had hated Moscow: it embodied the archaic in his realm. Moscow was a centre of the Old Believers - devout adherents of the Russian Orthodox rituals which had been observed before the Nikonian Church reforms of the 1650s (most contentiously, an alteration to the number of fingers used in making the sign of the cross) had brought them into line with those of the Greek Orthodox liturgy. The Old Believers clung to their ancient rituals as the embodiment of their religious faith. They saw the reforms as a heresy, a sign that the Devil had gained a hold on the Russian Church and state, and many of them fled to the remote regions of the north, or even killed themselves in mass suicides, in the belief that the world would end. The Old Believers pinned their faith on Moscow’s messianic destiny as the Third Rome, the last true seat of Orthodoxy after the fall of Constantinople. They explained its capture by the Turks as a divine punishment for the reunion of the Greek Orthodox Church with Rome at the Council of Florence in 1439. Fearful and mistrustful of the West, or any inno-

vation from the outside world, they lived in tightly knit patriarchal communities which, like medieval Moscow, were inward-looking and enclosed. They regarded Peter as the Antichrist - his city on the Baltic as a kingdom of the Devil and apocalypse. Many of the darker legends about Petersburg had their origins in the Old Belief.

With the building of St Petersburg, Moscow’s fortunes had declined rapidly. Its population had fallen, as half the city’s craftsmen, traders and nobility were forced to resettle in the Baltic capital. Moscow had been reduced to a provincial capital (Pushkin compared it to a faded dowager queen in purple mourning clothes obliged to curtsy before a new king) and until the middle of the nineteenth century it retained the character of a sleepy hollow. With its little wooden houses and narrow winding lanes, its mansions with their stables and enclosed courtyards, where cows and sheep were allowed to roam, Moscow had a distinct rural feel. It was called ‘the big village’ - a nickname it has retained to this day. As Catherine the Great saw it, though, Moscow was ‘the seat of sloth’ whose vast size encouraged the nobility to live in ‘idleness and luxury’. It was ‘full of symbols of fanaticism, churches, miraculous icons, priests and convents, side by side with thieves and brigands’,

6

the very incarnation of the old medieval Russia which the Empress wished to sweep away. When in the early 1770s the Black Death swept through the city and several thousand houses needed to be burned, she thought to clear the lot. Plans were drawn up to rebuild the city in the European image of St Petersburg - a ring of squares and plazas linked by tree-lined boulevards, quays and pleasure parks. The architects Vasily Bazhenov and Matvei Kazakov persuaded Catherine to replace the greater part of the medieval Kremlin with new classical structures. Some demolition did take place, but the project was postponed for lack of cash.

6

the very incarnation of the old medieval Russia which the Empress wished to sweep away. When in the early 1770s the Black Death swept through the city and several thousand houses needed to be burned, she thought to clear the lot. Plans were drawn up to rebuild the city in the European image of St Petersburg - a ring of squares and plazas linked by tree-lined boulevards, quays and pleasure parks. The architects Vasily Bazhenov and Matvei Kazakov persuaded Catherine to replace the greater part of the medieval Kremlin with new classical structures. Some demolition did take place, but the project was postponed for lack of cash.

After 1812 the centre of the city was finally rebuilt in the European style. The fire had cleared space for the expansive principles of classi-cism and, as Colonel Skalozub assures us in Griboedov’s drama

Woe from Wit,

it ‘improved the look of Moscow quite a lot’.

7

Red Square was opened up through the removal of the old trading stalls that had given it the feeling of an enclosed market rather than an open public spac e. Three new avenues were laid out in a fan shape from the square. Twisting little lanes were flattened to make room for broad straight

Woe from Wit,

it ‘improved the look of Moscow quite a lot’.

7

Red Square was opened up through the removal of the old trading stalls that had given it the feeling of an enclosed market rather than an open public spac e. Three new avenues were laid out in a fan shape from the square. Twisting little lanes were flattened to make room for broad straight

boulevards. The first of several planned ensembles, Theatre Square, with the Bolshoi Theatre at its centre, was completed in 1824, followed shortly after by the Boulevard and Garden Rings (still today the city’s main ring roads) and the Alexander Gardens laid out by the Kremlin’s western walls.

8

Private money poured into the building of the city, which became a standard of the national revival after 1812, and it was not long before the central avenues were lined by graceful mansions and Palladian palaces. Every noble family felt instinctively the need to reconstruct their old ancestral home, so Moscow was rebuilt with fantastic speed. Tolstoy compared what happened to the way that ants return to their ruined heap, dragging off bits of rubbish, eggs and corpses, and reconstructing their old life with renewed energy. It showed that there was ‘something indestructible’ which, though intangible, was ‘the real strength of the colony’.

9

8

Private money poured into the building of the city, which became a standard of the national revival after 1812, and it was not long before the central avenues were lined by graceful mansions and Palladian palaces. Every noble family felt instinctively the need to reconstruct their old ancestral home, so Moscow was rebuilt with fantastic speed. Tolstoy compared what happened to the way that ants return to their ruined heap, dragging off bits of rubbish, eggs and corpses, and reconstructing their old life with renewed energy. It showed that there was ‘something indestructible’ which, though intangible, was ‘the real strength of the colony’.

9

Yet in all this frenzy of construction there was never slavish imitation of the West. Moscow always mixed the European with its own distinctive style. Classical facades were softened by the use of warm pastel colours, large round bulky forms and Russian ornament. The overall effect was to radiate an easygoing charm that was entirely absent from the cold austerity and imperial grandeur of St Petersburg. Petersburg’s style was dictated by the court and by European fashion; Moscow’s was set more by the Russian provinces. The Moscow aristocracy was really an extension of the provincial gentry. It spent the summer in the country and came to Moscow in October for the winter season of balls and banquets, returning to its estates in the countryside as soon as the roads were passable following the thaw. Moscow was located in the centre of the Russian lands, an economic crossroads between north and south, Europe and the Asiatic steppe. As its empire had expanded, Moscow had absorbed these diverse influences and imposed its own style on the provinces. Kazan was typical. The old khanate capital took on the image of its Russian conqueror - its kremlin, its monasteries, its houses and its churches all built in the Moscow style. Moscow, in this sense, was the cultural capital of the Russian provinces.

Other books

Lauren Barnholdt - At The Party 02 - Telling Secrets by Lauren Barnholdt

Misty Blue by Dyanne Davis

Tree of Life and Death by Gin Jones

Love and Muddy Puddles by Cecily Anne Paterson

Extraordinary by Nancy Werlin

ROMAN: Fury of Her King (Kings of the Blood Book 2) by Julia Mills

Hollow Pike by James Dawson

The Cat Sitter’s Pajamas by Blaize Clement

Finding A Way by T.E. Black