Natasha's Dance (38 page)

1827), an idealized depiction of the female agricultural labourer in traditional Russian dress.

Below:

Vasily Perov:

Hunters at Rest

(1871). Like Turgenev, Perov portrays hunting as a recreation that brought the social classes together. Here the squire (left) and the peasant (right) share their food and drink.

Below:

Vasily Perov:

Hunters at Rest

(1871). Like Turgenev, Perov portrays hunting as a recreation that brought the social classes together. Here the squire (left) and the peasant (right) share their food and drink.

MOSCOW RETROSPECT.

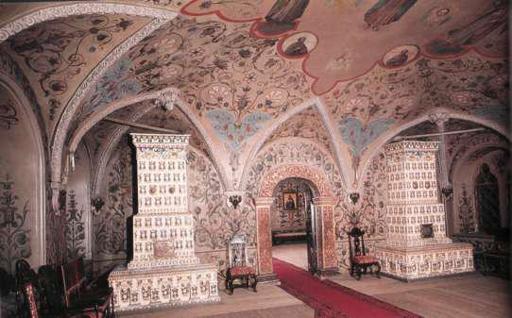

Above:

The Kremlin’s Terem Palace

Above:

The Kremlin’s Terem Palace

restored in the1850s

by Fedor Solntsev in the seventeenth-century Muscovite

by Fedor Solntsev in the seventeenth-century Muscovite

style, complete with tiled ovens and

kokoshnik-

shaped

arches.

Below:

Vasily

kokoshnik-

shaped

arches.

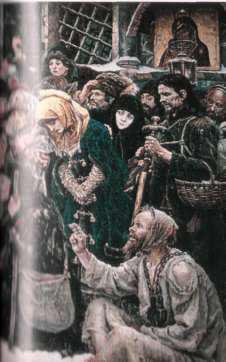

Below:

Vasily

Surikov:

The Boyar’s Wife Morozova

(1884). The faces were all drawn by

The Boyar’s Wife Morozova

(1884). The faces were all drawn by

Surikov from Old Believers living in Moscow.

The Faberge Workshop in Moscow crafted objects in a Russian style that was very different from the Classical and Rococo jewels it made in Petersburg.

Above:

Imperial Presentation Kovsh (an ancient type of ladle) in green nephrite, gold, enamel and diamonds, presented by the Tsar Nicholas II to the French Ambassador in 1906. Below: Silver

siren vase by Sergei Vashkov (1908). The female bird wears a

kokoshnik

and her

Above:

Imperial Presentation Kovsh (an ancient type of ladle) in green nephrite, gold, enamel and diamonds, presented by the Tsar Nicholas II to the French Ambassador in 1906. Below: Silver

siren vase by Sergei Vashkov (1908). The female bird wears a

kokoshnik

and her

wings are set with tourmalines.

THE ARTIST AND THE PEOPLE’S

CAUSE.

Ilya Repin’s

Portrait of Vladimir Stasov (1873),

the nationalist critic whose dogmatic views on the need for art to engage with the people were a towering and, at times, oppressive influence on Musorgsky and Repin. ‘What a picture of the Master you have made!’ the composer wrote. ‘He seems to crawl out of the canvas and into the room.’

Below:

Repin:

The Volga Barge Haulers (1873,).

Stasov saw the painting as a commen- tary on the latent force of social protest in the Russian people.

Opposite:

Ivan Kramskoi:

The Peasant Ignatii Pirogov

(1874) - a startlingly ethnographic portrait of the peasant as an individual human being.

Ilya Repin’s

Portrait of Vladimir Stasov (1873),

the nationalist critic whose dogmatic views on the need for art to engage with the people were a towering and, at times, oppressive influence on Musorgsky and Repin. ‘What a picture of the Master you have made!’ the composer wrote. ‘He seems to crawl out of the canvas and into the room.’

Below:

Repin:

The Volga Barge Haulers (1873,).

Stasov saw the painting as a commen- tary on the latent force of social protest in the Russian people.

Opposite:

Ivan Kramskoi:

The Peasant Ignatii Pirogov

(1874) - a startlingly ethnographic portrait of the peasant as an individual human being.

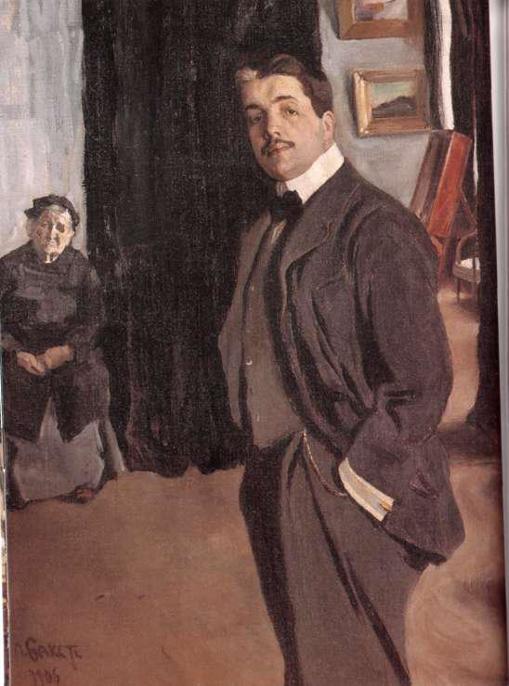

Leon Bakst:

Portrait of Diaghilev with his Nanny

(1906). Diaghilev had never known his mother, who had died when he was born.

Portrait of Diaghilev with his Nanny

(1906). Diaghilev had never known his mother, who had died when he was born.

Writers, too, immersed themselves in peasant life. In the words of Saltykov-Shchedrin, the peasant had become ‘the hero of our time’.

9

The literary image of the Russian peasant in the early nineteenth century was by and large a sentimental one: he was a stock character with human feelings rather than a thinking individual. Everything changed in 1852, with the publication of Turgenev’s masterpiece,

Sketches from a Hunter’s Album.

Here, for the first time in Russian literature, readers were confronted with the image of the peasant as a rational human being, as opposed to the sentient victim depicted in previous sentimental literature. Turgenev portrayed the peasant as a person capable of both practical administration and lofty dreams. He felt a profound sympathy for the Russian serf. His mother, who had owned the large estate in Orel province where he grew up, was cruel and ruthless in punishing her serfs. She had them beaten or sent off to a penal colony in Siberia - often for some minor crime. Turgenev describes her regime in his terrifying story ‘Punin and Barburin’ (1874), and also in the unforgettable ‘Mumu’ (1852), where the princess has a serf’s dog shot because it barks.

Sketches from a Hunter’s Album

played a crucial role in changing public attitudes towards the serfs and the question of reform. Turgenev later said that the proudest moment in his life came shortly after 1861, when two peasants approached him on a train from Orel to Moscow and bowed down to the ground in the Russian manner to ‘thank him in the name of the whole people’.

10

9

The literary image of the Russian peasant in the early nineteenth century was by and large a sentimental one: he was a stock character with human feelings rather than a thinking individual. Everything changed in 1852, with the publication of Turgenev’s masterpiece,

Sketches from a Hunter’s Album.

Here, for the first time in Russian literature, readers were confronted with the image of the peasant as a rational human being, as opposed to the sentient victim depicted in previous sentimental literature. Turgenev portrayed the peasant as a person capable of both practical administration and lofty dreams. He felt a profound sympathy for the Russian serf. His mother, who had owned the large estate in Orel province where he grew up, was cruel and ruthless in punishing her serfs. She had them beaten or sent off to a penal colony in Siberia - often for some minor crime. Turgenev describes her regime in his terrifying story ‘Punin and Barburin’ (1874), and also in the unforgettable ‘Mumu’ (1852), where the princess has a serf’s dog shot because it barks.

Sketches from a Hunter’s Album

played a crucial role in changing public attitudes towards the serfs and the question of reform. Turgenev later said that the proudest moment in his life came shortly after 1861, when two peasants approached him on a train from Orel to Moscow and bowed down to the ground in the Russian manner to ‘thank him in the name of the whole people’.

10

Of all those writing about peasants, none was more inspiring to

the Populists than Nikolai Nekrasov. Nekrasov’s poetry gave a new, authentic voice to the ‘vengeance and the sorrow’ of the peasantry. It was most intensely heard in his epic poem

Who Is Happy in Russia?

(1863-78), which became a holy chant among the Populists. What attracted them to Nekrasov’s poetry was not just its commitment to

Who Is Happy in Russia?

(1863-78), which became a holy chant among the Populists. What attracted them to Nekrasov’s poetry was not just its commitment to

the people’s cause, but its angry condemnation of the gentry class, from which Nekrasov himself came. His verse was littered with colloquial expressions that were taken directly from peasant speech. Poems such as

On the Road

(1844) or

The Peddlers

(1861) were practically tran-scriptions of peasant dialogue. The men of the forties, such as Turg-enev, who were brought up to regard the language of the peasants as too coarse to be ‘art’, accused Nekrasov of launching an ‘assault on poetry’.

11

But the students were inspired by his verse.

On the Road

(1844) or

The Peddlers

(1861) were practically tran-scriptions of peasant dialogue. The men of the forties, such as Turg-enev, who were brought up to regard the language of the peasants as too coarse to be ‘art’, accused Nekrasov of launching an ‘assault on poetry’.

11

But the students were inspired by his verse.

Other books

Hell Fire by Karin Fossum

The Buddha's Return by Gaito Gazdanov

Tempted by Mr. Write (What Happens in Vegas) by Sara Hantz

Princess of Dhagabad, The by Kashina, Anna

Split (Split #1) by Elle Boyd

Rise of the Death Walkers (The Circle of Heritage Saga) by Lawrence Nason Jr.

The Kingdom by the Sea by Paul Theroux

Embers by Antoinette Stockenberg

Shadowmage: Book Nine Of The Spellmonger Series by Terry Mancour

Breathing Underwater by Alex Flinn