Natasha's Dance (40 page)

seeing it instead as an epic portrait of the Russian character. What Repin meant, however, is more difficult to judge. For his whole life was a struggle between politics and art.

Repin was a ‘man of the sixties’-a decade of rebellious questioning in the arts as well as in society. In the democratic circles in which he moved it was generally agreed that the duty of the artist was to focus

13.

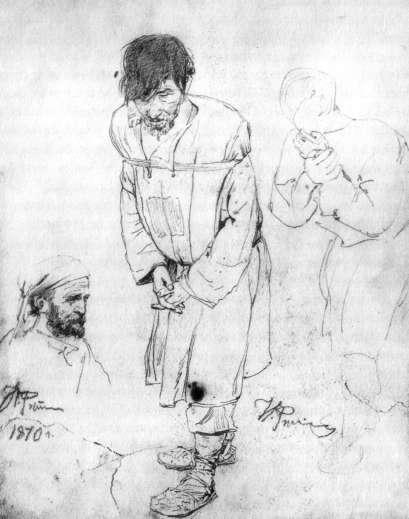

Ilia Repin: sketches for

The Volga Barge Haulers, 1870

Ilia Repin: sketches for

The Volga Barge Haulers, 1870

the attention of society on the need for social justice by showing how the common people really lived. There was a national purpose in this, too: for, if art was to be true and meaningful, if it was to teach the people how to feel and live, it needed to be national in the sense that it had its roots in the people’s daily lives. This was the argument of Stasov, the domineering mentor of the national school in all the arts.

Russian painters, he maintained, should give up imitating European art and look to their own people for artistic styles and themes. Instead of classical or biblical subjects they should depict ‘scenes from the village and the city, remote corners of the provinces, the god-forsaken life of the lonely clerk, the corner of a lonely cemetery, the confusion of a market place, every joy and sorrow which grows and lives in peasant huts and opulent mansions’.

29

Vladimir Stasov was the self-appointed champion of civic realist art. He took up the cause of the Wanderers in art, and the

kuchkists

in music, praising each in turn for their break from the European style of the Academy, and pushing each in their own way to become more ‘Russian’. Virtually every artist and composer of the 1860s and 1870s found himself at some point in Stasov’s tight embrace. The critic saw himself as the driver of a

troika

that would soon bring Russian culture on to the world stage. Repin, Musorgsky and the sculptor Antokolsky were its three horses.

30

29

Vladimir Stasov was the self-appointed champion of civic realist art. He took up the cause of the Wanderers in art, and the

kuchkists

in music, praising each in turn for their break from the European style of the Academy, and pushing each in their own way to become more ‘Russian’. Virtually every artist and composer of the 1860s and 1870s found himself at some point in Stasov’s tight embrace. The critic saw himself as the driver of a

troika

that would soon bring Russian culture on to the world stage. Repin, Musorgsky and the sculptor Antokolsky were its three horses.

30

Mark Antokolsky was a poor Jewish boy from Vilna who had entered the Academy at the same time as Repin and had been among fourteen students who left it in protest against its formal rules of classicism, to set up an

artel,

or commune of free artists, in 1863. Antokolsky quickly rose to fame for a series of sculptures of daily life in the Jewish ghetto which were hailed as the first real triumph of democratic art by all the enemies of the Academy. Stasov placed himself as Antokolsky’s mentor, publicized his work and badgered him, as only Stasov could, to produce more sculptures on national themes. The critic was particularly enthusiastic about

The Persecution of the Jews in the Spanish Inquisition

(first exhibited in 1867), a work which Antokolsky never really finished but for which he did a series of studies. Stasov saw it as an allegory of political and national oppression - a subject as important to the Russians as to the Jews.

31

artel,

or commune of free artists, in 1863. Antokolsky quickly rose to fame for a series of sculptures of daily life in the Jewish ghetto which were hailed as the first real triumph of democratic art by all the enemies of the Academy. Stasov placed himself as Antokolsky’s mentor, publicized his work and badgered him, as only Stasov could, to produce more sculptures on national themes. The critic was particularly enthusiastic about

The Persecution of the Jews in the Spanish Inquisition

(first exhibited in 1867), a work which Antokolsky never really finished but for which he did a series of studies. Stasov saw it as an allegory of political and national oppression - a subject as important to the Russians as to the Jews.

31

Repin identified with Antokolsky. He, too, had come from a poor provincial family - the son of a military settler (a type of state-owned peasant) from a small town called Chuguev in the Ukraine. He had learned his trade as an icon painter before entering the Academy and, like the sculptor, he felt out of place in the elite social milieu of Petersburg. Both men were inspired by an older student, Ivan Kram-skoi, who led the protest in 1863. Kramskoi was important as a portraitist. He painted lending figures such as Tolstoy and Nekrasov,

but he also painted unknown peasants. Earlier painters such as Venetsi-anov had portrayed the peasant as an agriculturalist. But Kramskoi painted him against a plain background, and he focused on the face, drawing viewers in towards the eyes and forcing them to enter the inner world of people they had only yesterday treated as slaves. There were no implements or scenic landscapes, no thatched huts or ethnographic details to distract the viewer from the peasant’s gaze or reduce the tension of this encounter. This psychological concentration was without precedent in the history of art, not just in Russia but in Europe, too, where even artists such as Courbet and Millet were still depicting peasants in the fields.

It was through Kramskoi and Antokolsky that Repin came into the circle of Stasov in 1869, at the very moment the painter was preparing his own portrait of the peasantry in

The Volga Barge Haulers.

Stasov encouraged him to paint provincial themes, which were favoured at that time by patrons such as Tretiakov and the Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, the Tsar’s younger son, who, of all people, had commissioned the

Barge Haulers

and eventually put these starving peasants in his sumptuous dining room. Under Stasov’s domineering influence, Repin produced a series of provincial scenes following the success of the

Barge Haulers

in 1873. They were all essentially populist - not so much politically but in the general sense of the 1870s, when everybody thought the way ahead for Russia was to get a better knowledge of the people and their lives. For Repin, having just returned from his first trip to Europe in 1873-6, this goal was connected to his cultural rediscovery of the Russian provinces - ‘that huge forsaken territory that interests nobody’, as he wrote to Stasov in 1876, ‘and about which people speak with derision or contempt; and yet it is here that the simple people live, and do so more authentically than we’.

32

The Volga Barge Haulers.

Stasov encouraged him to paint provincial themes, which were favoured at that time by patrons such as Tretiakov and the Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, the Tsar’s younger son, who, of all people, had commissioned the

Barge Haulers

and eventually put these starving peasants in his sumptuous dining room. Under Stasov’s domineering influence, Repin produced a series of provincial scenes following the success of the

Barge Haulers

in 1873. They were all essentially populist - not so much politically but in the general sense of the 1870s, when everybody thought the way ahead for Russia was to get a better knowledge of the people and their lives. For Repin, having just returned from his first trip to Europe in 1873-6, this goal was connected to his cultural rediscovery of the Russian provinces - ‘that huge forsaken territory that interests nobody’, as he wrote to Stasov in 1876, ‘and about which people speak with derision or contempt; and yet it is here that the simple people live, and do so more authentically than we’.

32

Musorgsky was roughly the same age as Repin and Antokolsky but he had joined Stasov’s stable a decade earlier, in 1858, when he was aged just nineteen. As the most historically minded and musically original of Balakirev’s students, the young composer was patronized by Stasov and pushed in the direction of national themes. Stasov never let up in his efforts to direct his protege’s interests and musical approach. He cast himself

in loco parentis,

visiting the ‘youngster’ Musorgsky (then thirty-two) when he shared a room with Rimsky-

in loco parentis,

visiting the ‘youngster’ Musorgsky (then thirty-two) when he shared a room with Rimsky-

Korsakov (then twenty-seven) in St Petersburg. Stasov would arrive early in the morning, help the men get out of bed and wash, fetch their clothes, prepare tea and sandwiches for them, and then, as he put it, when

‘we

[got] down to

our

business [my emphasis - O. F.]’, he would listen to the music they had just composed or give them new historical materials and ideas for their works.

33

The Populist conception of

Boris Godunov

(in its revised version with the Kromy scene) is certainly in line with Stasov’s influence. In a general sense all Musorgsky’s operas are ‘about the people’ - if one understands that as the nation as a whole. Even

Kbovanshchina

- which drove Stasov mad with all its ‘princely spawn’

34

- carried the subtitle ‘A national [people’s] music history’

(‘narodnaya muzikal’naya drama’).

Musorgsky explained his Populist approach in a letter to Repin, written in August 1873, congratulating him on his

Barge Haulers:

‘we

[got] down to

our

business [my emphasis - O. F.]’, he would listen to the music they had just composed or give them new historical materials and ideas for their works.

33

The Populist conception of

Boris Godunov

(in its revised version with the Kromy scene) is certainly in line with Stasov’s influence. In a general sense all Musorgsky’s operas are ‘about the people’ - if one understands that as the nation as a whole. Even

Kbovanshchina

- which drove Stasov mad with all its ‘princely spawn’

34

- carried the subtitle ‘A national [people’s] music history’

(‘narodnaya muzikal’naya drama’).

Musorgsky explained his Populist approach in a letter to Repin, written in August 1873, congratulating him on his

Barge Haulers:

It is

the people

I want to depict: when I sleep I see them, when I eat I think of them, when I drink I can see them rise before me in all their reality, huge, unvarnished, and without tinsel trappings! And what an awful (in the true sense of that word) richness there is for the composer in the people’s speech -as long as there’s a corner of our land that hasn’t been ripped open by the railway.

35

the people

I want to depict: when I sleep I see them, when I eat I think of them, when I drink I can see them rise before me in all their reality, huge, unvarnished, and without tinsel trappings! And what an awful (in the true sense of that word) richness there is for the composer in the people’s speech -as long as there’s a corner of our land that hasn’t been ripped open by the railway.

35

And yet there were tensions between Musorgsky and the Populist agenda set out for him by Stasov - tensions which have been lost in the cultural politics that have always been attached to the composer’s name.

36

Stasov was crucially important in Musorgsky’s life: he dis-

36

Stasov was crucially important in Musorgsky’s life: he dis-

covered him; he gave him the material for much of his greatest work; and he championed his music, which had been unknown in Europe in his lifetime and would surely have been forgotten after his death, had

it not been for Stasov. But the critic’s politics were not entirely shared by the composer, whose feeling for ‘the people’, as he had explained to Repin, was primarily a musical response. Musorgsky’s populism

was not political or philosophical - it was artistic. He loved folk songs

and incorporated many of them in his works. The distinctive aspects

of the Russian peasant song - its choral heterophony, its tonal shifts,

drawn out melismatic passages which make it sound like a chant

or a lament - became part of his own musical language. Above all, the

folk song was the model for a new technique of choral writing which Musorgsky first developed in

Boris Godunov.

building up the different voices one by one, or in discordant groups, to create the sort of choral heterophony which he achieved, with such brilliant success, in the Kromy scene.

Boris Godunov.

building up the different voices one by one, or in discordant groups, to create the sort of choral heterophony which he achieved, with such brilliant success, in the Kromy scene.

Musorgsky was obsessed with the craft of rendering human speech in musical sound. That is what he meant when he said that music should be a way of ‘talking with the people’ - it was not a declaration of political intent.* Following the mimetic theories of the German literary historian Georg Gervinus, Musorgsky believed that human speech was governed by musical laws - that a speaker conveys emotions and meaning by musical components such as rhythm, cadence, intonation, timbre, volume, tone, etc. ‘The aim of musical art’, he wrote in 1880, ‘is the reproduction in social sounds not only of modes of feeling but of modes of human speech.’

37

Many of his most important compositions, such as the song cycle

Savishna

or the unfinished opera based on Gogol’s ‘Sorochintsy Fair’, represent an attempt to transpose into sound the distinctive qualities of Russian peasant speech. Listen to the music in Gogol’s tale:

37

Many of his most important compositions, such as the song cycle

Savishna

or the unfinished opera based on Gogol’s ‘Sorochintsy Fair’, represent an attempt to transpose into sound the distinctive qualities of Russian peasant speech. Listen to the music in Gogol’s tale:

I expect you will have heard at some time the noise of a distant waterfall, when the agitated environs are filled with tumult and a chaotic whirl of weird, indistinct sounds swirls before you. Do you not agree that the very same effect is produced the instant you enter the whirlpool of a village fair? All the assembled populace merges into a single monstrous creature, whose massive body stirs about the market-place and snakes down the narrow side-streets, shrieking, bellowing, blaring. The clamour, the cursing, mooing, bleating, roaring - all this blends into a single cacophonous din. Oxen, sacks, hay, gypsies, pots, wives, gingerbread, caps - everything is ablaze with clashing colours, and dances before your eyes. The voices drown one another and it is impossible to distinguish one word, to rescue any meaning from this babble; not a single exclamation can be understood with any clarity. The ears are

* It is telling, in this context, that the word he used for ‘people’ was

‘liudi’

- a word which has the meaning of individuals - although it has usually been translated to mean a collective mass (the sense of the other word for people - the

‘narod’).

J. Leyda and S. Bertensson (eds.),

The Musorgsky Reader: A Life of Modeste Petrovich Musorgsky in Letters and Documents

(New York, 1947), pp. 84-5.

‘liudi’

- a word which has the meaning of individuals - although it has usually been translated to mean a collective mass (the sense of the other word for people - the

‘narod’).

J. Leyda and S. Bertensson (eds.),

The Musorgsky Reader: A Life of Modeste Petrovich Musorgsky in Letters and Documents

(New York, 1947), pp. 84-5.

assailed on every side by the loud hand-clapping of traders all over the market-place. A cart collapses, the clang of metal rings in the air, wooden planks come crashing to the ground and the observer grows dizzy, as he turns his head this way and that.

38

38

In Musorgsky’s final years tensions with his mentor became more acute. He withdrew from Stasov’s circle, pouring scorn on civic artists such as Nekrasov, and spending all his time in the alcoholic company of fellow aristocrats such as the salon poet Count Golenishchev-Kutuzov and the arch-reactionary T. I. Filipov. It was not that he became politically right-wing - now, as before, Musorgsky paid little attention to politics. Rather, he saw in their ‘art for art’s sake’ views a creative liberation from Stasov’s rigid dogma of politically engaged and idea-driven art. There was something in Musorgsky - his lack of formal schooling or his wayward, almost childlike character - that made him both depend on yet strive to break away from mentors like Stasov. We can feel this tension in the letter to Repin:

So, that’s it, glorious lead horse! The

troika,

if in disarray, bears what it has to bear. It doesn’t stop pulling… What a picture of the Master [Stasov] you have made! He seems to crawl out of the canvas and into the room. What will happen when it has been varnished? Life, power - pull, lead horse! Don’t get tired! I am just the side horse and I pull only now and then to escape disgrace. I am afraid of the whip!

39

troika,

if in disarray, bears what it has to bear. It doesn’t stop pulling… What a picture of the Master [Stasov] you have made! He seems to crawl out of the canvas and into the room. What will happen when it has been varnished? Life, power - pull, lead horse! Don’t get tired! I am just the side horse and I pull only now and then to escape disgrace. I am afraid of the whip!

39

Antokolsky felt the same artistic impulse pulling him away from Stasov’s direction. He gave up working on the

Inquisition,

saying he was tired of civic art, and travelled throughout Europe in the 1870s, when he turned increasingly to pure artistic themes in sculptures like

The Death of Socrates

(1875-7) and

Jesus Christ

(1878). Stasov was irate. ‘You have ceased to be an artist of the dark masses, the unknown figure in the crowd’, he wrote to Antokolsky in 1883. ‘Your subjects have become the “aristocracy of man” - Moses, Christ, Spinoza, Socrates.’

40

Inquisition,

saying he was tired of civic art, and travelled throughout Europe in the 1870s, when he turned increasingly to pure artistic themes in sculptures like

The Death of Socrates

(1875-7) and

Jesus Christ

(1878). Stasov was irate. ‘You have ceased to be an artist of the dark masses, the unknown figure in the crowd’, he wrote to Antokolsky in 1883. ‘Your subjects have become the “aristocracy of man” - Moses, Christ, Spinoza, Socrates.’

40

Other books

Night Mare by Piers Anthony

Mendel's Dwarf by Simon Mawer

Checkout by Anna Sam

I'm Travelling Alone by Samuel Bjork

Starved For Love by Nicholas, Annie

Neel Dervin and the Dark Angel by Neeraj Chand

Hope's Toy Chest by Marissa Dobson

Memento Nora by Smibert, Angie

Charming (Exiled Book 3) by Victoria Danann

31 noches by Ignacio Escolar