Nelson: Britannia's God of War (22 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

The loss of the Dutch fleet, coming on top of the defeat of the Spanish, left the French with few options for an offensive stroke against Britain. Making strategic combinations for a three- or four-pronged seaborne movement from the Texel, Brest, Cadiz and Toulon was no longer realistic. Bonaparte was sent to review the northern

invasion plans in February 1798, and did not like what he saw of the cold, muddy coast, or the feeble forces to hand. With no prospect of success, he was unwilling to risk his own position, and recommended against the attempt. Instead he advocated turning to the Levant, to strike at the Indian base of British prosperity. He had already secured the Ionian Islands for France, and with France dominating the Mediterranean it made sense to continue the career of conquest by seizing Malta and Egypt. This would counter the recent British seizure of the Cape of Good Hope from the Dutch, opening a new route to the east.

The wholly unjustified illegal seizure of these two territories demonstrated the fundamental change in the international order. Small states were no longer safe. Malta was held by the Order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, an organisation left over from the Crusades, which conducted permanent, if rather desultory warfare against Muslim states. While the islands lacked agricultural riches, and had limited supplies of water, they were located at the choke point between the eastern and western basins of the Mediterranean, and Grand Harbour at Valletta, secure behind its massive fortifications, was the best naval base in the central Mediterranean. The Knights had long since lost their crusading zeal, living in faded and apparently rather dissolute splendour amidst a Maltese population who despised them. The order was dominated by French Knights, and funded by property in various European countries. France had expropriated many of these lands, leaving the Knights short of funds, and increasingly irrelevant. The new state system of nations and empires had no place for such anachronisms: why should not the French replace them?

Egypt was in no better condition. Under the nominal authority of the Ottoman Sultans, defacto control had long passed to the Mamelukes, a warrior elite recruited from Circassian slaves. Under their petty tyranny the country had become a backward, crumbling, plague-ridden desert, full of the ruins of past glory. Many of these were connected with the two greatest conquerors of antiquity, Alexander and Caesar, men who fascinated Bonaparte. From a distance, Egypt seemed ripe for redevelopment through French science and political reform.

Foreign Minister Talleyrand supported Bonaparte, arguing that Egypt would be a substitute for the lost colonies of the West Indies. A combination of greed, fear and persuasive advocacy won over the

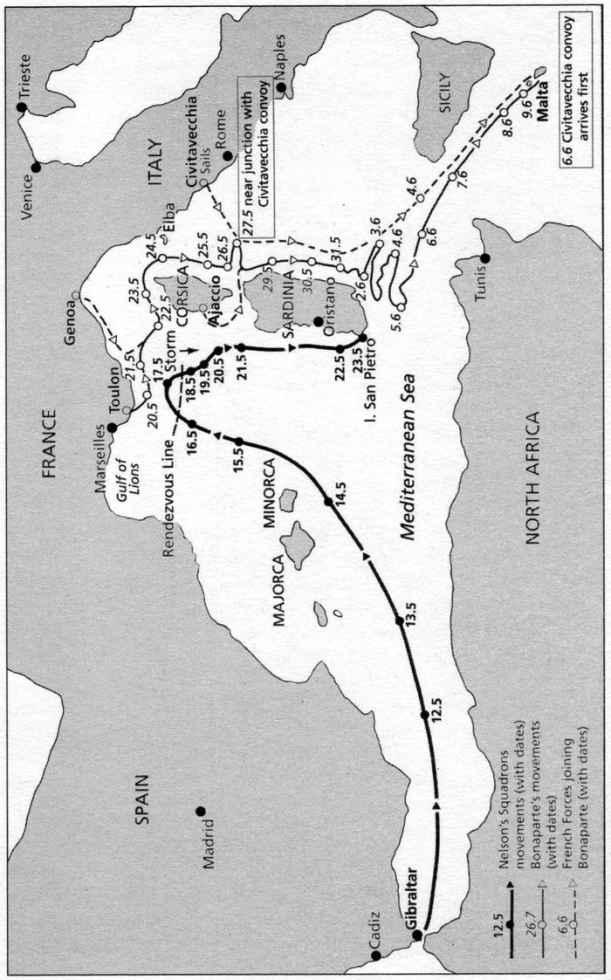

Directory in early March, with the eventual object of linking up with the Mysorean ruler Tippoo Sultan against British India. On 12 April, Bonaparte was appointed to overall command of an expedition whose ultimate aim was to drive the English from their oriental possessions and open the Red Sea to French traffic. Within a week troops and shipping began to collect at Toulon, Marseilles, Genoa, Civita Vecchia and, appropriately enough, Ajaccio. An army of thirty-one thousand, half of them veterans of the 1796–7 Italian campaign, with 170 guns and 1,200 horses, would be accompanied by a remarkable collection of scientists, scholars and artists, Arabic printing presses and assorted paraphernalia. The scale of the movement made complete secrecy impossible, but the ultimate object was well concealed. Bonaparte arrived at Marseilles in early May and addressed the troops, with his usual mixture of bombast and extravagant promises.

19

British agents around the Mediterranean were soon sending intelligence to London, and to the fleet off Cadiz. From early April it was evident that the French were preparing for a major move, and Naples and Sicily were the obvious targets. These reports had prompted St Vincent to plan a strategic reconnaissance, and led London to dispatch Nelson for the mission.

*

After calling at Gibraltar Nelson set off, promising St Vincent, ‘I do not believe any person guesses where I am going. It shall go hard, but I will present you at least with some frigates, and I hope something better.’ He would head along the Spanish coast past Cartagena and Barcelona, round Cape St Sebastian and look into Toulon, seeking information to guide his further movements.

20

The instructions for his battleship captains reflected the danger that so small a force faced when isolated in an enemy-controlled sea. They were to keep within sight of the flagship, even if they had to break off action. Two of the frigates were to head for Toulon, where they could cruise for up to ten days in search of intelligence, before rejoining at one of the pre-set rendezvous. In an attempt to preserve his secrets for a few more days he had the squadron sail from Gibraltar after dark on 8 May.

21

Unfortunately they were delayed by light airs and were fired on by Spanish batteries the next morning.

22

On 17 May one of the frigates captured a French corvette off Cape Sicie, about seventy miles from Toulon. Interrogating the crew provided considerable information on Bonaparte and his armament, although none on his destination. Cruising about seventy-five miles south of Toulon, Nelson was ideally placed to pick up any ships heading for Italy, or the Straits. Intelligence gathered by Saumarez indicated the French had embarked cavalry. Whatever the object, however, Nelson had no doubt that his duty was to fight the enemy, if he found them at sea.

23

Although he had only three battleships, it is probable that he envisaged using them to break up the French fleet, leaving the frigates to attack the transport ships. With numerous French warships and transports running south along the Italian coast there was every chance of contact if Nelson hovered between Toulon and Sardinia. Instead he ran into a storm.

Nelson in the Mediterranean

A furious gale from the north-north-west hit the squadron on 20 May. No significant damage was done to the other ships of the squadron, but Nelson’s flagship, the

Vanguard

, was severely affected. Berry seems to have misread the weather, setting up the higher masts for light airs. Saumarez and Ball did the opposite. So while the other two seventy-fours had sails blown out,

Vanguard

lost all three topmasts, and then her foremast. Effectively crippled, with the foremast beating against the side of the ship,

Vanguard

was in serious danger. Nelson took command after the disaster, and managed to wear the ship off the rocky coast of Corsica. He now planned to anchor in a Sardinian bay to the south, and ordered the

Alexander

to take his flagship in tow. Despite exemplary seamanship, this apparently simple task occupied over eight hours. However, light airs and a strong current took them past the anchorage, and left the two ships drifting towards the coast, and unable to anchor. Unless the wind picked up the two ships were going to run aground. But for the audacious seamanship and determination of Ball, one or both of them would have been wrecked. In a passage of high drama, Nelson ordered Ball to save to his own ship, but he refused and kept calm. Finally a breeze picked up, and the ungainly partnership anchored safely between the island of San Pietro and the mainland at midday on 23 May.

Once anchored Nelson hastened to thank Ball, whom he had hitherto considered a conceited coxcomb. Typically, he took his newfriend into his inner circle without hesitation, and came to trust his judgement on questions far beyond seamanship. Nelson also had toacknowledge another mistake: Berry was not up to the job, both hisseamanship and his judgement left a great deal to be desired. For thenext two months Nelson would take a far more active part in handling

the ship than he might have hoped. However, he would not have dreamt of disgracing Berry, or even replacing him, at this critical juncture. Remarkably, Nelson showed no signs of hesitation: he would repair the ship and carry on with his mission. He did not consider the obvious options of returning to the fleet with his crippled flagship, nor shifting into another ship and sending his flagship back. Instead, the carpenters of the three battleships quickly created a temporary or jury rig for the

Vanguard

.

Five days after anchoring with her rigging in ruins the

Vanguard

was back at sea: she sailed well and would not compromise the mission.

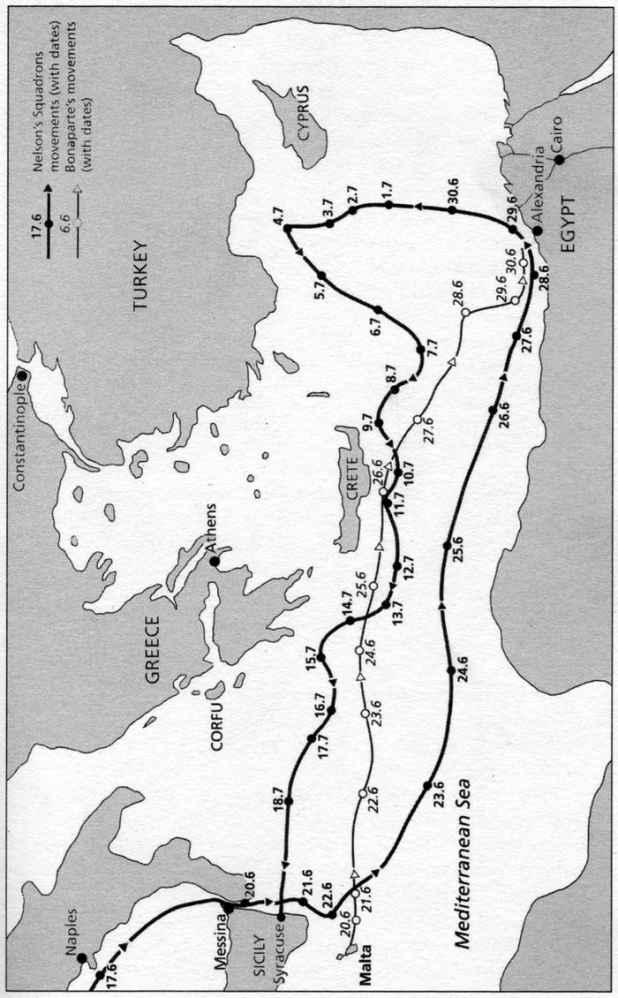

A fresh prize revealed the French were at sea, and on 5 June Hardy in the brig

Mutine

joined the squadron at the rendezvous off Toulon to inform him of Troubridge’s reinforcement. The new ships linked up with Nelson on 7 June, and the entire force was together on Sunday 10th. He now commanded thirteen seventy-four-gun ships – all English-built, medium-sized units, with almost identical rigs, armament and crew. The fifty-gun

Leander

was an odd packet, too big to be a frigate, but too weakly armed and built for the line of battle and no faster under sail. St Vincent sent her because he had no more frigates. As Nelson’s frigates, hearing of his accident, had returned to Gibraltar, scouting duties would be left to the tiny

Mutine

.

St Vincent had intended that the

Orion

should rejoin his fleet, as Saumarez was anxious to go home, but the damage to the flagship persuaded Nelson to keep him.

Over the next seven weeks of almost constant cruising, chasing and refitting, the squadron would build on the very superior attainments it possessed, reaching the highest levels of proficiency in all aspects of its task. These ships were fit champions for England – none better existed – and they would be tested to the limit before their work was done. Nelson had no doubt he would beat the French, but in 1798 the Mediterranean was a vast expanse of water with very limited communications, surrounded by a host of potential destinations and harbours where a fleet might find shelter behind batteries. His hardest task would be to find the enemy, and the key to this would be the acquisition and processing of intelligence. British officials in neutral ports and cities could help, but only if Nelson could make contact with them; intelligence from London and even reports sent by St Vincent would be out of date. The best source would be other ships. Prizes and neutral vessels could reveal much. The French knew this and deliberately

destroyed as many passing vessels as they could, but Nelson stopped and spoke to at least forty-one craft between May and August. As a result, he was never far from Bonaparte’s armada, eventually overtaking the French at sea.

24

The squadron orders reveal an admiral bent on battle. The day after Troubridge joined he divided the squadron into starboard and larboard squadrons of seven and eight ships, commanded by himself and Saumarez, with Troubridge leading the line as he had so memorably at Cape St Vincent.

25

Later a more conventional formation was adopted, with Nelson, Saumarez and Troubridge commanding distinct divisions. If he found the French at sea Nelson would use two units to engage their warships while the third cut up the transports.

26

Whatever tactical divisions he adopted Nelson insisted that they keep in visual contact. He wanted his force together, in supporting distance, ready to exploit any fleeting opportunity for battle.

27

While Nelson had been close to disaster on the west coast of Sardinia, Bonaparte’s force had found easier conditions to the east, as the various detachments linked up and headed for Malta. Arriving on 9 June, the French landed on the following day, securing the islands and the massive fortress of Valletta by a combination of force and treachery on the 12th. After installing a small garrison the main force left on the 18th. At this stage Nelson was less than a hundred miles astern, making far better time than the huge, unwieldy French force.