Nelson: Britannia's God of War (6 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

CHAPTER I

1

For details of this, and every other ship on which Nelson served, with a wealth of period detail and operational history, see Goodwin,

Nelson’s

Ships:

A

History

of

the

Vessels

in

which

he

Served,

1771

–

1805

2

Goodwin, p. 3 5

3

Nelson to Cornwallis 1790;

Manuscripts

of

Cornwallis

Wykeham

Martin

, pp. 341–2

4

Clarke and McArthur (1840) [hereafter C&M] I p. 24

5

C&M I p. 14.

6

Nicolas I pp. 21–2

7

Vincent,

Nelson,

Love

and

Fame

, p. 33

8

McNairn, A.,

Behold

the

Hero:

General

Wolfe

and

the

Arts

in

the

18th

Century

. Liverpool, 1997

9

Pocock,

Young

Nelson

in

the

Americas

, offers a comprehensive and rewarding study of this episode.

10

Lambert, ‘Sir William Cornwallis’, in LeFevre and Harding,

Precursors

of

Nelson

11

Mahan p. 27, Oman, p. 40 and Warner p. 38, attribute it to his merit. Southey, Laughton and Vincent pp. 42–3 simply accept the appointment.

12

Nelson to Suckling 14.1.1784; Nicolas II p. 479

13

Jenkinson to Sandwich 12.2.1781; Add. MS 38,308 f. 81

14

Rodger,

The

Insatiable

Earl:

A

life

of

John

Montagu,

4

th

Earl

of

Sandwich

, pp. 176–9. See also Sandwich to Jenkinson 19.1.1781; BL Add. MS 38,217 f. 253

15

Nelson to William Nelson 7.5.1781; Nicolas I pp. 42–3

16

Jenkinson to Sandwich 10.4.1781; Add. MS 38,308 f. 113

17

Walker,

The

Nelson

Portraits

, pp. 13–18

18

Hood to Pigot 22.11.1782; Hannay ed.

Letters

of

Lord

Hood;

1781

–

83

, p. 15

19

C&M; 1. p. 52. The anecdote was supplied by the Duke after 1805 and is therefore suspect.

20

Nelson to Locker 25.2.1782; Nicolas I p. 723

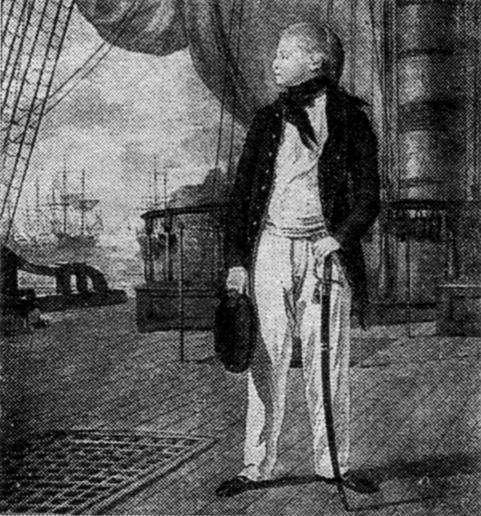

Prince William Henry on board the

Prince

George

CHAPTER II

Numerous examinations of the period of Nelson’s career between the American and the French revolutions have characterised it as a sequence of events in which he demonstrated the strands of greatness, browbeat his elders, obtained a wife and then wasted his time and talent ashore. Too little attention has been given to the motives that underlay Nelson’s actions, and the potentially fatal damage he inflicted on his career prospects. It is more accurate to see this period as one in which Nelson desperately – if unsuccessfully – sought opportunities to further his career and his family interest.

Once he had paid off the

Albemarle

, Nelson made a brief visit to Norfolk, but the society of his family held little interest for a much-travelled young captain with a career to make, who fancied himself already at the elbow of the great. He soon moved on to France, where he and the fellow officer who accompanied him intended to learn the language of the enemy and profit from the lower cost of living. He had probably been advised by Suckling, Locker, Hood or another mentor that this skill would help his career − after all, the most advanced tactical and theoretical works on naval subjects were published in France. But Nelson wasted the opportunity: his hostility to the French was evident in every letter, a pair of pretty French girls distracted him from his study, and he soon fell in love with Elizabeth Andrews, an English clergyman’s

daughter. Hoping, without reason, that she might consent to become his wife, he sent a mean-spirited, unpleasant letter to his uncle, demanding an allowance, its tone veering between self-pity and moral blackmail. But the cause was hopeless, and Nelson quickly found an excuse to leave. After only two months, he was back in London, socialising with Hood and visiting Lord Howe at the Admiralty, where he was offered a ship. It is uncertain whether this followed an approach by Suckling or a recommendation from Hood − but it was not a question of pure merit. The political scene in Britain was complicated. After a series of government changes and reconstructions between March 1782 and December 1783, William Pitt the Younger had become Prime Minister, but few expected his ministry to last. Hood, one of Pitt’s high-profile supporters and MP for Westminster, had real leverage, but it would not survive the return to government of his rival for the seat at Westminster, the Whig leader Charles James Fox.

*

Nelson’s new ship, HMS

Boreas,

was another twenty-eight-gun frigate. A purpose-built British ship, now ten years old, she had seen considerably more service than her new captain, and was already in commission.

1

Nelson hoped to go to the East Indies, but soon found himself destined for the Leeward Islands station. Nor would this be his last disappointment. Brother William insisted on joining as the chaplain, then the pilot ran the ship aground in the Thames, and Admiral Hughes’ wife and daughter joined an already crowded ship, an inconvenience made doubly trying by the added cost and the ‘eternal clack’ of the woman. Nonetheless, Nelson retained his infectious good humour: he occupied his time on the voyage educating and encouraging an unusually numerous crop of midshipmen, ensuring that all went aloft and took their navigation seriously.

After calling at Madeira for wine, water and fresh food,

Boreas

arrived in Carlisle Bay, Barbados in June 1784. As the senior captain on the station, and ranking second in command, Nelson would have much to do, especially as Admiral Hughes preferred a quiet life ashore. His orders were to protect the northern group of islands − Montserrat, Nevis, Anguilla, St Christopher and the Virgin Islands − and secure British commerce, which included preventing illegal trade. Though the duties seemed rather mundane for a thrusting young captain trying to make his name, Nelson would court controversy throughout the commission.

Soon after her arrival

Boreas

was tied up at Antigua, the other squadron base, to wait out the hurricane season. Here he fell under the spell of Mary Moutray, the charming and accomplished wife of the Dockyard Commissioner. Flirting with an older woman seemed to be almost the only relaxation for the squadron’s captains − apart from alcohol, which the abstemious Nelson abhorred. Cruising through the Saintes passage, where so much glory had been won, Nelson must have been struck by the relaxed atmosphere of the station, especially in comparison with the discipline expected of Hood’s fleet only two years before. He applied a harsh regime of punishment for this commission,

2

and he was quick to react to any oversight or inattention that appeared to slight his office, his dignity or the rights of the Crown. He was ill suited to peacetime service: his intense, analytical approach to his profession appeared out of place in the heavy, torpid atmosphere of the sugar islands, where life could be short and the temptation to pursue pleasure almost overwhelming.

Hughes commanded a powerful force − a fifty-gun ship, four frigates and two sloops − which reflected the proximity of the interlocking French islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe and the extensive commercial interests at stake. However, the French provided few problems, unlike the community the squadron was sent to protect. Only rarely did Nelson escape the routine of the station, surveying a Danish harbour, and very pointedly escorting a French warship that appeared to be intent on surveying the British islands. Whenever possible Nelson had his ship sail in company with others on the station, to conduct tactical exercises.

3

He wanted to retain the link with war service − the reason he had joined the Navy. Moreover, the exercises kept the ship busy, and gave the men a focus for their loyalties. The

Boreas

was a clean and well-ordered ship with a healthy crew.

The key to Nelson’s tour of duty in the West Indies was the clash of economic and strategic interests that followed the separation of the American colonies from the British Empire. Until 1776 American shipping and commerce had been an important strategic and economic asset, playing a major role in the French wars and the growth of the British economy. Colonial status allowed the Americans to trade freely with the West Indian sugar islands, exchanging grain, timber, fish, tar, tobacco and other produce for sugar, rum, molasses and money. American independence brought an end to this thriving and mutually beneficial inter-colonial trade.

Post-war strategic considerations were complex: as Britain’s fourth or fifth largest export market, and the source of the largest single import, the sugar islands were a major state concern. Moreover, the maintenance of naval mastery required a healthy merchant marine. But now the Americans had placed themselves outside the system, their sailors and shipbuilders should not be allowed to profit at the expense of loyal subjects of the crown, nor should the sugar islands keep their connection with the rebels, in case they too left the empire. Initial attempts to retain the old connection in a new form were quickly replaced by more hostile measures. The Navigation Acts, long regarded as the foundation of naval power, would be enforced against the Americans. The Order in Council of 2 July 1783 stated that American goods were only to enter the West Indies in British or colonial ships, which had to be British-built, and British-manned − a popular measure in London; American ships could only trade direct with Britain.

The West Indian lobby, a powerful group of MPs linked to the planters and merchants, attacked the Order in Council when it came up for renewal at the end of 1783, but they were soundly defeated by the argument that to open the trade to the Americans would undermine the commercial basis of British naval power, and on 31 May 1784 the Order in Council was upheld. In 1786 a measure to encourage British shipping was introduced by William Suckling’s friend Charles Jenkinson, now Chairman of the Committee for Trade. British shipping recovered quickly after the end of the war, soon outstripping the pre-war levels. The rise of British commerce provided the maritime resources for the next war: many of the men whose jobs Nelson had been so anxious to secure in 1784−6 would serve in the Royal Navy after 1793. Both the policy and the application, in short, would be vindicated.

4

Why did Nelson take this issue so seriously? This question is generally answered by emphasising his commitment to duty, regulation and honour. But these concepts, so necessary to the creation of a certain type of Nelson, hardly square with his sinecurist behaviour in continuing to pay his brother William for a further two years after he had left the ship.

5

Nelson’s concern to advance his family was typical of the eighteenth century, and such family connections also provide the key to his remarkable conduct in the West Indies.

After Maurice Suckling’s death, his brother William, Commissioner

in the Excise Office, became the most important family member for the advancement of the young Nelson’s naval career. William’s links with powerful and ambitious ministers would prove invaluable, while his house in Kentish Town was a frequent destination for the young officer when in town. Nelson may well have encountered the debates over the Navigation Acts and the Order in Council while staying with Suckling in late March 1784, already knowing he was destined for the Leeward Islands.

6

The Excise Office raised revenue on a limited number of dutiable commodities, notably beer, cider, wine, malt, hops, salt, leather, soap, candles, wire, paper and silk. In the eighteenth century, excise – collected by the producers, and passed on unseen to the public – was the most attractive method of increasing state income. It provided around half of all revenue and was regularly raised to pay for wars. The nine Commissioners sitting in London supervised the office, acted as a court of appeal and attended the Lords of the Treasury once a week.

7

His role in the Excise gave Suckling access to the key players in Government, including the Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

8

However, it was one thing to pass a popular measure in London, and quite another to uphold it in the West Indies, where the local commercial classes had long been in the habit of trading with the Americans. The trade proved impossible to eliminate, although it was restricted. Whatever the ministers had intended, the majority of West Indian officials, both Governors, and Crown Lawyers, connived in attempts to evade the statutes. Their early resort to financial power, through expensive legal threats, reflected the basic issue at stake: American ships could bring in goods cheaper than alternative suppliers.

By January 1785 Nelson had realised that Hughes was overlooking a trade made illegal under the recent Order in Council, and subverting the Navigation Acts that were essential to national security. He refused to join Hughes in his connivance with the local authorities, basing his stand on the law and his own dignity. This was hardly going to please Hughes who, when Nelson produced the relevant Act and Orders, claimed he had not seen them. Desperate to square the circle created by his own acts and Nelson’s unwelcome zeal, Hughes ordered his officers to admit foreign ships if the local authorities gave them clearance. Nelson simply observed that this was illegal, and ran counter to the efforts being made back in Britain to suppress such trade. Not content with teaching the admiral his duty, Nelson copied

the correspondence back to the Admiralty.

9

Hughes could not assert his authority, because he was so obviously in the wrong. Instead he quietly left Nelson and the Collingwood brothers Cuthbert and Wilfred to enforce government policy, and incur the animosity of the islanders. Nelson sought government backing through an extensive correspondence. The resulting argument with Governor Shirley of Antigua was only resolved by a response from London.

10

Knowing his approach would be popular in London, Nelson wrote to the Home Secretary, Lord Sydney, who had also received a full report from Governor Shirley on Collingwood’s initial actions. Meanwhile Nelson and Wilfred Collingwood had been stopping and searching suspicious trading vessels, many using false papers. The resulting seizures were entirely legal, but profoundly unpopular, provoking local merchants to issue a claim for damages. Just in case he had not caught the attention of the Ministers, Nelson then sent a statement of his services through Lord Howe to the King. Hughes merely reported proceedings and kept his head down. Nelson’s correspondence with older and more experienced officers had the tone of a self-righteous, hectoring sermon. Little wonder it reduced Hughes and Shirley to splenetic rage, a condition exacerbated by the realisation that the arrogant puppy was perfectly correct.

Nelson’s confidence was based on sound advice from London. He had been corresponding with Suckling on points of shared professional concern, debating the legal niceties of his position with him and seeking opinions from the Excise Board solicitor.

11

He doubtless sent his uncle copies of the official submissions, in case the originals went astray. By September he knew his stand had been backed in London, gaining Treasury approval and legal support. He was reconciled with Hughes, who must have been relieved that Nelson made no allegations against him. While Nelson affected to be outraged by the arrival of an Admiralty letter commending Hughes for his non-existent zeal in suppressing the illegal trade, his comments should not be taken too seriously.

12

They were, like much of his more vitriolic output, only meant for his friends. He knew that admirals always took the credit for the good work of their subordinates, along with a healthy share of the prize money and any other rewards on offer. However, he took the trouble to set out his case, including the evidence against Hughes, in a memorandum which was seen by a few key figures. Nelson had learnt a valuable lesson, and would not allow his merits to pass unnoticed in

future. The seeds of his concern to manage his own publicity, so obvious after 1793, were sown in the Leeward Islands.