Niagara: A History of the Falls (8 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

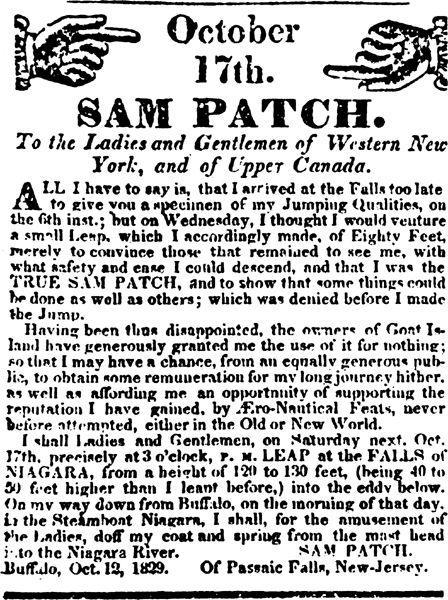

Patch jauntily obliged and produced a poster attesting to “the reputation I have gained, by Airo-Nautical Feats, never before attempted, either in the Old or New World.” He announced he would plummet 120 feet into the abyss from a platform fastened to the cliff of Goat Island between the two falls. The distance was probably less than one hundred feet (the

Colonial Advocate

placed it at eighty-five) because the platform was secured one-third of the way down the cliff.

On a rainy Saturday, as crowds lined both sides of the river as well as the banks of the island, Patch appeared, shed his shoes, and climbed a ladder to the platform. It was only large enough for one man and wobbly to boot, but Patch was unconcerned, acknowledging the cheers of the multitude. Then he stood up, took a handkerchief from around his neck, tied it to his waist, and kissed the Stars and Stripes flying from the stand. He stood erect, feet together, arms at his sides, toes pointing downward, took a lungful of air, and stepped off into the torrent.

“He’s dead, he’s lost!” the crowd shouted – or so one report claimed. But he was very much alive. His head burst from under the water; the crowd went wild; and Sam, singing merrily to himself, swam into the arms of the nearest spectator and cockily declared that “there’s no mistake in Sam Patch!”

The press was predictably ecstatic. “Sam Patch has immortalized himself,” burbled the

Colonial Advocate

. “He has done what mortal never did before.” The Buffalo

Republican

called Patch’s jump “the greatest feat of the kind ever effected by man.” Emboldened by the experience, Patch left immediately for the nearby Genesee Falls, leaped from a height of 120 feet before five thousand awestruck spectators, hit the water in a kind of belly-flop, and was instantly killed.

His body was not recovered until the following spring, and as so often happens, there were those who claimed he wasn’t dead. So began the Sam Patch legend. “SAM PATCH ALIVE!” ran a headline in the New York

Post

less than a month after his death. People began to see Patch everywhere; some even claimed they had spoken to him. Others wrote poems, plays, stories, songs, novels, even a fake autobiography of the Jersey Jumper. And at Niagara, guides pocketed tips by pointing to the exact spot where Sam Patch had made his last successful leap.

If certain eccentrics were tempted to exploit the aura of the macabre that still hung over the Falls, others were drawn to the cataract by a craving for the sublime and the beautiful. While Sam Patch was drawing the spectators at the lower extremity of Goat Island, a strange young man named Francis Abbott was taking his ease at the upper end where the roar of the rapids drowned out the roar of the crowd. Here, in the core of the island forest, the Hermit of Niagara found the solitude he craved. Abbott had nothing in common with the Jersey Jumper but a watery fate.

In his long, chocolate-coloured cloak, his feet bare, Abbott was a familiar if unusual figure as he wandered, aloof and ascetic, violin in hand, from Goat Island to the shallows where he bathed at least twice a day in the coldest weather, often surrounded by floating chunks of ice.

He had arrived at the Falls on foot on June 18, 1829, a tall, well-formed man carrying a roll of blankets, a flute, a book, and a cane. He put up at Ebenezer Kelly’s modest inn on the American side and asked if there was a library or a reading room in the community. There was. He repaired to it, deposited three dollars, borrowed a book and some sheet music, and then bought a violin. He announced he would stay for a few days.

He stayed longer, for the Falls had captured him – obsessed him. “In all my wanderings,” he told the innkeeper, “I have never met with anything in nature that equals it in sublimity, except perhaps Mount Etna during an eruption.” He was astonished, he said, that some visitors arrived, gazed briefly on the spectacle, and left – all in a single day. He proposed to remain at least a week. A traveller might as well, he said, “examine in detail all the museums and sights of Paris, as to become acquainted with Niagara, and duly appreciate it in the same space of time.”

A week, it developed, was not long enough. He talked of staying a month, perhaps six months. He fixed upon Goat Island as suitably distant from the crowd and asked Augustus Porter for permission to build a hut on its shores. That was the last thing Porter wanted – new buildings disturbing the sylvan setting. But Abbott was allowed to move into the only dwelling on the island, a one-storey log cabin occupied by a family that had, apparently, been on the scene before Porter. They gave him space and let him do his own cooking. When the family moved he had the place to himself – an ideal situation; then, when another family moved in, he left the island and built a small cottage on the main shore directly opposite the American Falls.

But it was Goat Island that seduced him. With the pet dog he had acquired he tramped back and forth along its upper shore until his bare feet had beaten a hard path through the woods. He continued to bathe in a small cascade that lay in the narrows between Goat and its diminutive neighbour, Moss Island.

The Porters had constructed a shaky pier that led from Goat, the main island, above a series of half-submerged rocks to the Terrapin Rocks, three hundred yards out in the torrent. From the far edge of the pier a single piece of timber projected over the cataract. To the consternation of onlookers, the Hermit would saunter out to the rocks in his bare feet and then out onto the timber, walking heel and toe, back and forth, maintaining his balance while his long, unshorn hair streamed out behind him in the wind and the spray. Sometimes he would even stand on one leg, perform an elegant pirouette, then drop to his knees to gaze into the cauldron below. On occasion he would alarm the watchers still more by letting himself down by his hands to hang directly over the Falls for fifteen minutes at a time.

He explained to one of the ferrymen that when crossing the ocean he had seen young sailors perform even more perilous acts aloft on the masts. Since he himself expected to go to sea again, he said, he must inure himself to such dangers. This brief, tantalizing glimpse into his past life served only to deepen the mystery of his background. Who was this man whose uncanny lack of fear and whose flirtation with fate seemed more a matter of cool curiosity than a death wish? Sometimes at midnight he was seen to walk alone in the most hazardous spots; at those times he avoided his fellows “as if he had a dread of man.” Who was he?

Probably an English officer on half pay, or perhaps a remittance man. He was well educated and clearly had travelled widely in Europe and Asia. He played several musical instruments, was a fair artist, and on those rare occasions when he was inclined to be sociable could indulge in sophisticated conversation. But at other times he shunned human companionship, refused to speak or listen to anyone, communicated his wishes by writing on a slate, and didn’t bother to shave. Then his only covering was a blanket in which he wrapped himself.

He was, in short, a recognizable type, one of the first of a breed of eccentric Victorian Englishmen who would turn up from time to time in remote global outposts – in China ports, on South Sea beaches, in western cow towns, or in Africa’s dark heart. For such a stereotype, Niagara offered an ideal setting.

Two years almost to the day from his arrival, Francis Abbott was seen by a ferryman to fold his garments neatly on the shore below the boat landing and enter the water. He seemed to keep his head under for a suspiciously long time, but the ferryman was used to Abbott’s odd behaviour and had other duties to attend to. When he next looked, Abbott was gone. Nor was he ever seen alive again, though his body was not found in the river until eleven days later.

His death was as mysterious as his life. Was it accident or suicide? No scrap of paper in his hut remained to provide a clue, even though he was known to scribble away day after day, tearing up the results at night. His faithful dog stubbornly guarded the door and was removed with difficulty. Within, his flute, violin, guitar, and music books lay scattered about. On a crude table were found a portfolio and the leaves of a large book, all blank. Not even his name had been inscribed on them.

His cool flirtation with death and his ambiguous fate were the stuff from which legends are born. Nothing could be more appropriate to Niagara’s aura than this uncanny tale, which would be retold in story and verse and even on canvas. Unlike so many others, Francis Abbott sought nothing from the spirit of Niagara – not profit or fame or power – except peace, and that, in the end, is what it provided.

Chapter Three

1

“That Enchanted Ground”

2

The father of geology

3

Spanning the gorge

4

John Roebling’s bridge

1

“That Enchanted Ground”

The Fashionable Tour, which was also known as the Northern Tour, began at Savannah, Georgia, in the early spring and wended its way through the various states toward Canada. As a leading guidebook explained in 1830, “the oppressive heat of summer in the southern sections of the United States, and the consequent exposure to illness, have long induced the wealthy part of the population to seek … the more salubrious climate of the north.” The tour wound through Richmond, Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Saratoga Springs, and then by way of the Erie Canal to Buffalo and Niagara Falls before continuing on to Montreal and the New England states.

In the mid-1830s, the popular image of the cataract began to change as more visitors sought it out. The canal era was at its height and the railway era was dawning. The Welland Canal between Lakes Erie and Ontario had opened in 1829. By 1834 a horse-drawn railroad connected Buffalo with the Erie Canal at Black Rock. In 1836, a second line with steam locomotives ran from Black Rock to Manchester. The following May, another horse-drawn line opened between Lockport and the Falls. The twenty-one-mile trip took seven and a half hours, and travellers emerged from the little carriages choking and sputtering, their mouths, ears, and eyes as grimy as their clothes. Matters improved in August when the tandems of trotting horses gave way to steam power.

In spite of such primitive conditions, it was a more comfortable journey than earlier travellers had endured. As a result it attracted a new class of people – well-to-do tourists who, perhaps because they could afford a longer stay, came to see the Falls as both sublime

and

beautiful. “Beautiful and glorious” was the phrase used by Lydia Sigourney, a popular and prolific author of moral verse who produced several cloying poems about the Falls. It was to this class of self-indulgent strangers that the handsome new hotels would cater.

“Beautiful” was also the word that Harriet Beecher (later, Stowe), the future author of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

, used when she came up by stage and steamer through Toledo and Buffalo in 1834. Miss Beecher was enraptured, not terrified. “Oh, it is lovelier than it is great,” she exulted. “… so veiled in beauty that we gaze without terror.…” As she stood on Table Rock, she felt what so many newcomers were beginning to feel – a sense of peace, of tranquillity and stillness. This represented a considerable literary leap from the Burkean concept of the sublime, but then, Burke was going out of fashion.

From the vantage point of the great overhanging ledge, the young woman not only felt at peace but was also half prepared to deliver herself to the depths below. “I felt as if I could have

gone over

with the waters; it would be so beautiful a death; there would be no fear in it. I felt the rock tremble under me with a sort of joy. I was so maddened that I could have gone too, if it had gone.”

The young Nathaniel Hawthorne, then on the verge of a distinguished literary career, also arrived that year by stage from Lewiston, intent on treating the cataract as a shrine. “Never,” he wrote, “did a pilgrim approach Niagara with deeper enthusiasm, than mine.” In his thinly disguised fictional satire, the future novelist told how he kept putting off his first view of the Falls, saving it up for later as a child saves a sweet, even shutting his eyes tight when he heard a fellow passenger exclaim that the cataract had come into view. Nor did he rush “like a madman” to the scene, preferring instead to revel in delicious anticipation, taking his dinner at the hotel, then lighting a leisurely cigar until, at last, “with reluctant step” and feeling like an intruder, he walked toward Goat Island. “Such has often been my apathy,” he explained, “when objects, long sought, and earnestly desired, were placed within my reach.”

The tollgate at the bridge gave him another excuse for dallying. He signed the visitors’ book and pored over several of the entries. He examined a stuffed fish and a display of beaded moccasins. He bought himself a carved walking stick of curly maple, fashioned by the Tuscarora Indians. Only then did he cross the bridge to gaze upon the tumbling waters.