Niagara: A History of the Falls (4 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Always a bit of a braggart, jealous of the exploits of his contemporaries, ever eager to take all the credit to himself, Hennepin patronized and belittled the explorer in his accounts, displaying little of the charity associated with his cloth – not the most amiable of companions, one must conclude, in the exploration of darkest America. Later on, when he and two comrades were captured by the Sioux, he managed to make enemies of both his fellow prisoners before their release.

Yet he was certainly courageous, hard working, energetic, adventurous, and, above all, curious, and for that we must be grateful. After Hennepin arrived in Canada in 1675, he was sent as a missionary to Fort Frontenac, on the present site of Kingston, Ontario, then a wild and remote outpost in the land of the Iroquois. La Salle, meanwhile, had obtained the Kitig’s authority to explore the western regions of New France. In those days no exploration was undertaken without the presence of a priest. In 1678, Hennepin’s superiors ordered him to accompany La Salle on his travels. Nothing could have pleased him more.

Hennepin was to be part of an advance company of sixteen under Dominique La Motte de Luciere charged with the task of setting up a fort and building a barque on Lake Erie. Travel was hazardous in those times. The company set off from Fort Frontenac in savage November weather aboard a ten-ton brigantine, tossed about fiercely in the mountainous waves. Hugging the shoreline for safety, the crew eventually managed to run the ship into the protection of a river mouth (probably the Humber) near the present site of Toronto. That night the river froze and the following morning the entire company was obliged to hack out a passage to the lake with axes.

On December 6 they reached the mouth of the Niagara, which no ship had yet penetrated. It was too dark to enter, and so they stood out five miles from shore, trying to manage a little sleep in their cramped quarters. The following morning, December 7, they landed on the western (now the Canadian) bank at a small Seneca village. Here, the friendly Indians with a single fling of the net pulled in some three hundred small fish, all of which they gave to the newcomers, “ascribing their luck in fishing to the arrival of the great wooden canoe.”

To the Indians, and indeed to the early explorers, the lower Niagara and the Falls above were little more than an impediment, forcing a long and weary portage over steep ridges. When Hennepin and several of the party paddled up the river, they found their way blocked by the current of the first of the great gorges through which the Niagara rushes. They were forced to abandon their craft and set off on snowshoes, toiling up the miniature mountain now known as Queenston Heights.

Following the indistinct portage trail of the Indians, they could see, through a screen of trees, the columns of mist rising from the great cataract and hear the rumble of its waters. But they did not pause, for they were anxious to move beyond the Falls to locate a spot where La Salle could build his barque (to be called

Griffon)

. They camped that night at the mouth of Chippawa Creek (now the Weiland River), scraping away a foot of snow in order to build a fire. The next day, surprising herds of deer and flushing out flocks of wild turkeys, they retraced their steps and spent half a day gazing on Niagara’s natural wonders.

Standing on the high bank above the cataract, they peered through a tangle of snow-covered evergreens and deciduous trees, naked and skeletal. They clambered down to the rim of the gorge for a better view, probably in the vicinity of Clifton Hill, a wintry forest then, a neon carnival today. And so Hennepin reached the very lip of the precipice.

See him now on that chill December morning, shivering in his grey habit, staring down into “this most dreadful Gulph” and then averting his eyes because of the mesmerizing effect. “When one stands near the Fall and looks down,” he was to write, “… one is seized with Horror, and the Head turns round, so that one cannot look long or steadfastly upon it.”

The great cataract was farther downstream then. To Hennepin’s gaze, it formed an almost even line from bank to bank, curving gently from the cliffside of Goat Island to what is now the Canadian shore, its crestline only half its present length. On the far side he could see that the cataract between the river bank and Goat Island was broken into two parts, as it is today (the smaller being the Luna or Bridal Veil Falls), while close to the vast overhang of Table Rock on the near shore a fourth jet cascaded into the gorge (and, though he did not record it, there was probably a fifth). That one has long since vanished, as a result of the Falls’ implacable backward erosion.

It is said that the priest, who carried a portable altar strapped to his back, went down on his knees to make an obeisance to his Deity, his ears assailed as if by Divine thunder. True or not, it is a plausible fancy, for Hennepin, by his own account, was shaken by the “dreadful roaring and bellowing of the Waters” and by the spectacle of the fearsome chasm, which he and his comrades “could not behold without a shudder.” Small wonder! At that point, as each second ticked by, 200,000 cubic feet of water – the equivalent of a million bathtubs emptying – was being hurled into the gorge from the precipice.

These falls were unlike any that Hennepin had seen or heard of. He had probably viewed alpine cataracts in Switzerland, for he had travelled through southern Europe, but this fall defied the conventional image of how a cataract should look. It is its width, not its height, that makes Niagara spectacular. Taken together, the three falls are more than twenty times as wide as they are high. Their massiveness makes them unique. Fifty other waterfalls in the world have more height than Niagara, but of these only Victoria Falls is broader.

Any falls with which the Father was familiar would have been slender – long, lacy columns of tumbling water bouncing from crag to crag like some sure-footed alpine creature. But here there were no mountains, and that astonished and puzzled Hennepin. The river coursed across a flat, forested plain and then, without warning, split in two and hurled itself over a dizzy cliff. “I could not conceive,” he wrote, “how it came to pass that four great Lakes … should empty themselves at this Great Fall, and yet not drown a good part of America.”

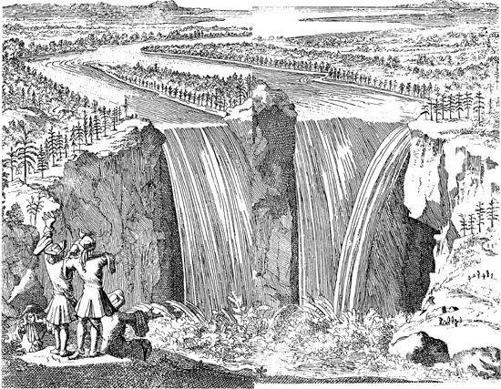

He could not free himself of the stereotype of the mountain cataract. Europe got its first visual rendering of the Falls in an engraving based on the priest’s description. It shows the Horseshoe Falls twice as high as they are broad, the American Falls three times as high. And there are mountains in the distance! That became the basis for all pictorial representations for the next sixty years. Even as late as 1817, the Hennepin version of the Falls, complete with mountains, was appearing on maps of the region.

Later, Hennepin made his way down the steep bank of the gorge, struggling over great boulders and slabs of slippery shale, threading his way between fallen trees and through a frozen web of vines and branches, to stand at the edge of the boiling river and to look up, through the veil of mist, at the half-obscured cataract. Here the thunder of the waters was so oppressive that he hazarded the guess it had driven away the Indians who had once lived in the vicinity, existing on the flesh of deer and waterfowl swept over the brink. To remain, Hennepin intimated, was to court deafness.

First drawing of Niagara Falls based on Hennepin’s description

Among those literary wanderers of the day who sought a wide and appreciative audience, exaggeration was the fashion. Tales abounded of strange and exotic sights in the world’s secret crannies – of dragons and devils, half-human creatures, sea beasts, two-headed beings, one-eyed cannibals, and all manner of wild and mysterious fauna. Hennepin was not free of hyperbole. Gazing across at the lesser cataract and watching the sheet of water pouring over the protruding edge of dolostone, he realized it would be possible to walk behind the falling waters. Later, he insisted that the ground under that fall “was big enough for four coaches to drive abreast without being wet.” That was a gross exaggeration.

It was in Hennepin’s interest, as an ambitious author, to make “this prodigious cadence of water” even more stupendous. In his

Description de la Louisiane

, he created a waterfall three times the true height, boosting it from 170 feet to 500 – a prodigious cadence indeed. In his later revised description of 1697, he added another hundred feet. The book made his reputation in Europe. In Canada it established him as “un grand Menteur,” a great liar, as Pehr Kalm, a Swedish naturalist, discovered half a century later. Hennepin did not confine this embroidery to his description of Niagara Falls. In his writings he did his best to undercut La Salle’s contributions and establish himself as the real explorer of the Mississippi.

Hennepin’s description of “this prodigious frightful Fall” was enough to send shivers up his readers’ spines. No doubt that was his purpose. It was to him “the most Beautiful and at the same time most Frightful Cascade in the World.” He peppered his descriptions with adjectives designed to awe his readers: “a great and horrible cataract” … “frightful abyss” … “horrible mass of water” … “a sound more terrible than that of thunder.”

It was these overheated descriptions that stimulated in Europeans the macabre vision of the New World – a wild, weird land of dark, impenetrable forests where painted savages lurked behind every tree and a gargantuan cataract foamed and roared in the unknown interior of the continent. Hennepin also wrote of rattlesnakes squirming beneath the sheet of water, and later travellers followed with tales of eels wriggling among the rocks below, of great eagles soaring above the spray, and, at the end of a gloomy gorge, a vast whirlpool, like the Charybdis of antiquity, waiting to entrap the unwary visitor.

Thus was established the image of the Falls as a dread and mystic place. It would take the best part of a century to soften that perception.

3

“The most awful scene”

For most of the eighteenth century the Falls remained almost as remote as the moon. A couple of eyewitness accounts in French followed Hennepin’s, but nothing appeared in English until 1751 when a translation of Kalm’s travel diary added to the Falls’ reputation as a fearsome cataract. “You cannot see it without being quite terrified,” he wrote. He described how birds flying over the boiling rapids became so soaked with spray that they plunged to their deaths, of how flocks of waterfowl swimming above the Falls were swept over the precipice, and of how the bodies of bear, deer, and other animals that tried to cross the upper river were found broken to pieces at the bottom of the cascade.

Kalm retold the tale of two Iroquois trapped on Goat Island – an incident that had occurred a dozen years earlier but was still the talk of the region. The pair had gone deer hunting well above the Falls but, tipsy from brandy, had awakened in their canoe to find it heading for the abyss. Paddling frantically, they managed to reach the island before being swept over, but then realized they were trapped between the two cascades.

Faced with slow starvation, they built a rope ladder from basswood bark, tied one end to a tree, and dropped the other down the 170 feet of the Goat Island cliff and into the torrent below. They climbed down the rock face and into the water, intending to swim ashore, but could make no headway against the great eddy caused by the collision of waters from the two cataracts. Each time they tried to escape, the fury of the stream below the Falls hurled them back. At last, badly bruised and scratched, they were forced to haul themselves back up to their island prison.

After several days they managed to attract the attention of some of their comrades on shore, who hastened to the fort at the river’s mouth to seek help. The commandant ordered long pikestaffs tipped with iron to be made. Armed with these, two Indians volunteered to attempt a crossing to the northeastern (American) side of the island to try to rescue the starving pair. “They took leave of their friends as if they were going to their death,” and then, steadying themselves precariously with a pole in each hand, they managed to make the agonizing journey through the rocks and shallows to the island – something never before or since attempted. The victims, who had been without food for nine days (except, perhaps, for berries and wild grasses) were thus successfully guided to safety.

It took considerable daring and a stout heart to hazard the descent from the lip of the gorge to the slippery tangle of rocks and roots at the river’s edge. Hennepin, who had worked his way down the cliff beside the Horseshoe Falls, claimed that the opposite cliff was so steep no one could negotiate it. But one man did.

He was a romantic and adventurous French diplomat, Michel-Guillaume Jean de Crèvecoeur, who visited the Falls with a companion named Hunter in July of 1785. By this time, as a result of the Conquest of 1759, the region was no longer in French hands. The western side was English; the eastern side had just been ceded to the United States following the American War of Independence. Crèvecoeur himself had been arrested by the Americans as a spy in 1783 but had easily established his neutrality (he was a friend of George Washington) and served as consul of France in New York. Now this well-travelled and literate visitor had decided to attempt the perilous descent of the sheer cliff on the American side of the gorge. He and Hunter tied a stout rope to a tree about fifty feet below the crest of the American Falls. Clinging to it and finding footholds in the crevices in the rock, they descended some 150 feet to the bottom, “not without having experienced the greatest bodily fatigue, but also some fearful apprehensions.”