North Yorkshire Folk Tales (16 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

In the year 17— a solitary cottage stood in a lonely gill not far from Arncliffe. A more wretched habitation the imagination cannot picture, it contained a single room inhabited by an old woman called Bertha, who was, throughout the valley, accounted a wise woman.

I was at that time very young and unmarried, and far from having any dread of her would frequently talk to her and was always glad when she called at my father’s house. She was tall, thin and haggard. Her eyes were sunk deep in their sockets and her hoarse masculine voice was anything but pleasant. The reason I took such delight in her company was because she was possessed of great historical knowledge and related events that had occurred two or three centuries ago in such a detailed manner that many a time I believed that she had seen them for herself.

In the autumn of 17— I set out one evening to visit her cottage. I had never seen inside and was determined to. I knocked at the gate and she told me to come in. I entered. The old woman was seated on a three-legged stool by a peat fire, surrounded by three cats and an old sheepdog.

‘Well,’ she exclaimed. ‘What brings you here?’

‘Don’t be offended,’ I answered. ‘I’ve never seen inside your cottage and wanted to do so. I also wished to see you perform some of your “incantations”.’ Bertha noticed that I spoke the last word ironically.

‘So you doubt my power, think me an imposter and consider my incantations mere jugglery? Well, you may change your mind. Sit down and in less than half an hour you shall see evidence of my power greater than I have allowed anyone else to witness!’

I obeyed and approached the fireside, looking round the room as I did so. The only furnishings were three stools, an old deal table, a few pans, pictures of Merlin, Nostradamus and Michael Scott, a cauldron and a mysterious sack. The witch, having sat by me a few minutes, rose and said, ‘Now for our incantation; watch me but don’t interrupt.’ She then drew a chalk circle on the floor and in the midst of it placed a chafing dish filled with burning embers; on this she fixed the cauldron that she had half-filled with water.

She then told me to stand on the opposite side of the circle. She opened the sack and taking from it various ingredients threw them into the pot. Amongst other things I noticed a skeleton head, bones of different sizes and the dried carcasses of some small animals. All the time she did this she continued muttering some words in an unknown language.

At length the water boiled and the witch, presenting me with a glass, told me to look through it at the cauldron. I did so and saw a figure enveloped in the steam. At the first glance I did not know what to make of it, but soon I recognised the face of N—, a good friend of mine. He was dressed in his usual way but seemed unwell and pale. I was astonished and trembled.

The figure having vanished, Bertha removed the cauldron and put out the fire.

‘Now!’ she said. ‘Do you doubt my power? I have brought before you the form of a person who is some miles from here, I am no imposter!’

I only wanted to get out of there but as I was about to leave Bertha said, ‘Stop! I haven’t finished with you. I will show you something more wonderful. Tomorrow at midnight go and stand on Arncliffe Bridge and look at the water on the left side of it. Don’t be afraid. Nothing will hurt you.’

‘Why should I go? It’s a lonely place. Can I take someone with me?’

‘No!’

‘Why not?’

‘Because the charm will be broken,’

‘What charm?’

‘I’m not going to tell you any more. Do it. You will not be harmed.’

That night I lay awake unable to sleep and during the next day I was so preoccupied that I was unable to attend to any business.

Night came and I went to Arncliffe Bridge. I shall never forget the scene; it was a lovely night; the full moon was sailing peacefully through a clear deep-blue cloudless sky and its silver beams were dancing on the waters of the Skirfare beck. The stillness was broken only by the murmuring of the stream, while the scattered cottages and the autumn woods all united in a picture of calm and perfect beauty.

I leaned against the left battlement of the bridge, trying to be calm. I waited in fear for a quarter of an hour, half an hour, an hour. Nothing happened. I listened; all was silent. I looked around; I saw nothing. Surely, I thought, it must be midnight by now. Bertha has made a fool of me! I breathed more freely. Then I jumped as the clock of the neighbouring church suddenly chimed. I had mistaken the hour. I resolved to stay a little longer.

Then, as I gazed in the stream, I heard a low moaning sound and saw the water violently troubled. The disturbance continued for a few moments before it ceased and the river became calm and peaceful again

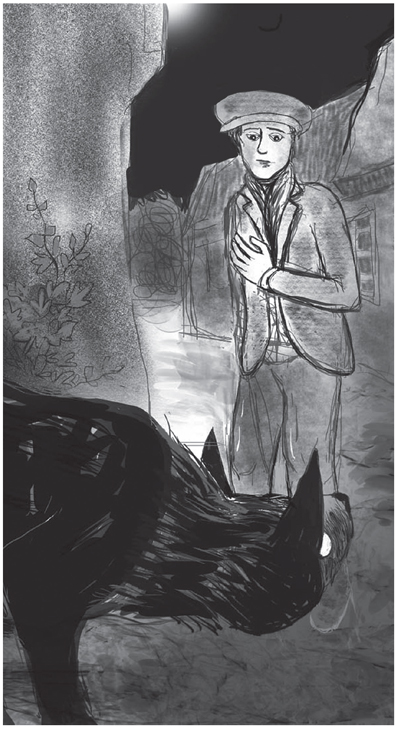

I wondered what it could mean. Who moaned? What caused the disturbance? Full of fear I hurried home, but turning the corner of the lane that led to my father’s house, I was startled as a huge dog crossed my path. A Newfoundland, I thought. It looked at me sadly. ‘Poor fellow!’ I exclaimed. ‘Have you lost your master? Come home with me until we find him. Come on!’ The dog followed me, but by the time I got home, it had disappeared. I supposed it had found its master.

The following morning I went to Bertha’s cottage again and once again found her sitting by the fire.

‘Well, Bertha,’ I said, ‘I obeyed you. Last night I was on Arncliffe Bridge.’

‘What did you see?’

‘Nothing except a slight disturbance of the stream.’

‘I know about that, but what else?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Nothing! Your memory is failing you!’

‘Oh, I forgot. On the way home I met a Newfoundland dog belonging to some traveller.’

‘That dog never belonged to a mortal,’ she said. ‘No human is his master. The dog you saw was Barguest. You may have heard of him!’

‘I’ve often heard tales of Barguest but I never believed them. If the old tales are true someone will die after he appears.’

‘You are right. And a death will follow last night’s appearance.’

‘Whose death?’

‘Not yours.’

Bertha would tell me no more, so I went home. Less than three hours later I heard that me friend N—, whose figure I had seen in the cauldron steam, had that morning committed suicide by drowning himself at Arncliffe Bridge at the very spot where I saw the disturbance of the stream!

LD

N

ANNY

Nidderdale

Come in this minute or Old Nanny will get you!

Old Nanny overlooked his pigs and they all died!

Old Nanny’ll find you! If you go down there!

Who is Old Nanny/Old Alice/Old Peggy? You may think that she is an old woman living just beyond the end of the village, or that she haunts the crossroads or the churchyard or sits below the gibbet. You may use her to frighten your children away from abandoned houses, or old wells, or even other people’s property, but one thing is certain: once you have let her into your mind, she will set up lodgings in your imagination. Then, you had best beware!

![]()

One night a farmer living near Stokesley wakes to find Old Nanny standing at the end of his bed. He knows it is her because all the hair on his head is standing on end and his heart is beating fit to bust.

‘What do you want?’ he gasps.

‘Get the gold!’ she says. ‘Get the silver!’

‘I’ve neither one!’ he stammers, though it is a lie.

‘Get the gold! Get the silver!’

This time she points out of the window towards the orchard, where the new spring leaves shine in the moonlight as if they are themselves made of silver.

The farmer begins to think that perhaps she has not come to rob him after all.

‘Under the foremost!’ says Old Nanny. ‘Take the silver; leave the gold. Give it to Annie.’

‘That dirty old witch who lives just beyond village end? Why her?’

‘Give it to Annie!’ she repeats. She takes a step backwards, out of the moonlight and is gone.

The farmer lies awake panting and unable to get back to sleep, but as soon as the sun begins rise he leaps from his bed. The farm men yawning and rubbing their eyes as they come into the kitchen are amazed when he strides through them.

‘Where’s farmer going at sparrow’s fart?’ mutters one. They all stare out of the back door as the farmer goes first to the cart shed for an old spade and then marches straight towards the orchard.

‘Eh! Farmer’s crackin’!’ they opine gleefully.

The farmer digs under the tree closest to the house, and, just as Old Nanny has said, he unearths a chest of treasure. It is full of silver and gold. He waits until all the men have gone about their work and then brings it into the house. In his room he runs his fingers through the coins. How delightfully heavy they are!

He does not for a moment consider giving anything at all to Annie; lonely, miserable, hungry and cold in her little tumbledown cottage. He thinks, ‘The chest was in my orchard, on my land and I dug it up. It’s mine!’

But once Old Nanny gets into your mind you’re never free again. From the moment he shuts the chest on that decision everything begins to go wrong for him. He does not notice immediately, though he remarks to his surprised foreman on how unseasonably cold it has suddenly become.

That night he wakes to see Old Nanny sitting on a chair by the fire he has had lit in his bedroom. She does not speak, just looks at him. He pretends not to see her and turns over.

The next night she is there again, and the next.

‘T’awd bitch’ll never wear me down!’ the farmer mutters to himself, pulling the blankets over his head.

The next evening he finds himself, uncharacteristically, heading for the alehouse. ‘Just a bit of a stiffener,’ he tells the surprised landlord, ‘to face her down.’ He does not say who ‘her’ is. The following evening he goes again. Soon it becomes a regular habit. His men increasingly have to go and help bring him home. He often says that Old Nanny is following him, but that he will face her down, t’awd bitch – then he laughs drunkenly. The men look nervously behind them but there is never anyone there.

‘Farmer’s finally cracked!’ they say.

The farmer never sleeps well any more until dawn is near. He rises later and later and stops supervising his men’s work. Inevitably they take advantage. The farm starts to go to rack and ruin.

He still rides weekly to Stokesley market but as often as not the horse will have to find its own way home with its owner slumped drunkenly asleep in the saddle.

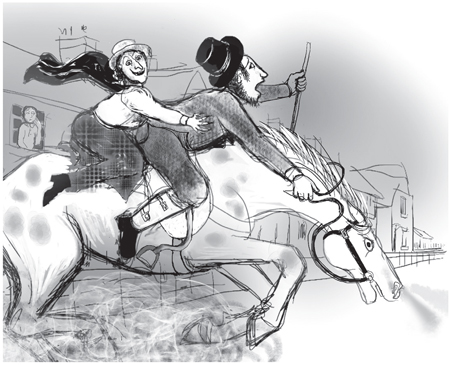

One wild and windy Saturday night, however, he is not asleep. On the contrary, the villagers are themselves woken by shouting, the clatter of hooves and a terrified neighing. As they throw their shutters open the farmer gallops furiously by, spurring his horse unmercifully. As he passes they hear him shouting ‘I will! I will! I will!’ Then some see that up behind him is a hunched shape, a small woman in black. She wears the straw hat of an ordinary farm labourer’s wife, but she is clinging to the farmer like a cat with her long pointed fingernails.

The farm gate is shut and though the newly awoken men run into the yard at the noise of hooves, they are not fast enough to open it. That does not stop the farmer; he brings his whip down again and again on the horse’s flank. ‘I will! I will! I will!’ he screams.