North Yorkshire Folk Tales (17 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

‘He’s niver going to leap t’gate!’ the men gasp, but, yes, there he goes!

Some of the men try to grab the reins of frightened horse as it lands skidding on the cobblestones, but it rears violently as they approach, throwing off its passengers. The farmer flies through the air and hits his own doorstep with a crack they can all hear. The foreman runs to his side. He kneels down to help him – too late; his master’s head is covered with blood, his eyes are open and sightless.

Of Old Nanny there is no sign.

She hasn’t gone far though.

She’s in your head now …

HE

N

INE

OF

H

EARTS

Swaledale

George Winterfield was a stealer of hearts. The girls of Leeming, near the River Swale, were attracted by his good looks and easy charm. He was excitingly wild too, known for his drinking and gambling, his jokes, his daring.

He had a girl, promised her marriage, as everyone knew, but somehow there was never quite enough money or the time was not quite right – maybe next year? She waited patiently, but as time wore on, she became increasingly desperate. The other village girls had been jealous when she bagged George, so they were not inclined to be kind to her as the prospect of her marriage appeared to recede indefinitely. George himself remained as friendly and charming to them all as if he was not promised at all.

One evening he was playing cards with his mates in Leeming Mill. George played most winter evenings when there was nothing else to do. The miller’s wife brewed a good ale, his fire was warm and the company, for the most part, jolly – unless they were losing, of course. There were four of them: the miller himself, George and two old school friends, John Braithwaite and Tim Farndale. None of them was a rich man, so the pot was not very large, but, even so, George was a canny player with something of a reputation to keep. Occasionally a passing visitor would be invited to join the game, usually going away poorer than he had arrived. When that happened the girls of Leeming would get all sorts of small treats from George; rides at the fair, ribbons, sweetmeats and so on. It will never be known what the poor lass to whom he was promised thought of this.

On this particular evening, the frost was crackling on the windows and the miller’s fire was crackling on the broad hearth. The men sat down to their game with pleasure, but something strange happened. George was dealt eight consecutive hands containing the nine of hearts.

All you mathematicians will know that, provided all the cards are properly shuffled, the odds of the next hand also having a nine of hearts in it are the same as for the first. But those who play with the Devil’s Picture books are not mathematicians, at least the men at this table were not. To them it seemed impossible that the nine of hearts would turn up for a ninth time.

Tim was so sure he wagered a guinea that it would not. George, who had been losing all night, was not prepared to wager more than a shilling that it would. John opted out. The miller thoughtfully filled their mugs with ale wondering whether he would lay a bet of his own. He looked at the high colours of the others, their bright drunken eyes and shivered unexpectedly, despite the heat. Something was wrong somehow. He glanced around the room where the shadows cast by the leaping fire suddenly seemed ominous. The flickering confused him. For a moment he thought he … but no, no one was there.

‘Come on man! Art thoo in?’ He realised that the others were waiting for him. ‘Nay, lads, I’ll sit this’un out.’

John dealt the cards. George moved to lay his bet.

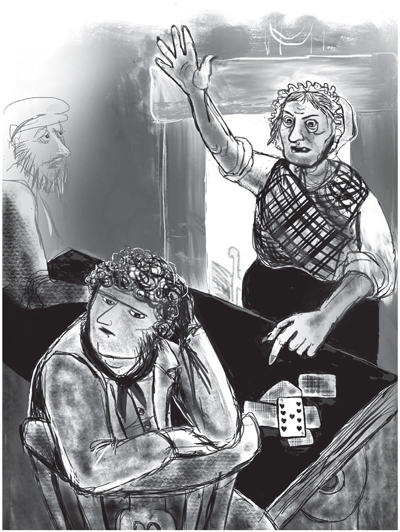

‘Put thy brass in thy pocket,’ said a harsh voice, just behind him. Everyone jumped and looked around. Awd Molly stood there, Molly Cass, named locally as a witch by giggling girls. Normally the miller, who did not hold with such foolishness, would have invited her over to the fire for a warm, but her sudden appearance, from nowhere it seemed, filled him with alarm.

‘Put thy brass in thy pocket,’ she said again to George. ‘Thy brass is not for him and his brass is not for thee.’ So great was her reputation for ferocity, that neither George nor Tim dared disobey her. They pocketed their money. Molly moved forwards to the table and stared hard at the backs of George’s cards, which lay there still unexamined.

‘George, thoo’s got it again. The nine. Tek up thy hand and see.’

George shrugged with an affectation of carelessness and picked up his cards. There, shining as red as drops of blood, was the ninth nine of hearts.

‘George, thoo’s hit it eight times already and the Old ’Un (the Devil) is in thee now. He’ll not leave thee till he’s got thee altogether! Thoo’s thrown away thy chance, so I’ve pitched it into the Swale. Now the Swale’s waiting for thee, George. It’s going to be thy bridal bed!’

The others stared at George whose ruddy face had paled. He forced a laugh. ‘What’s thoo blethering about Awd Molly? I’ve not thrown away any chance.’

‘Where is thy bride?’

George froze at the words. He knew that he had not treated Mary well, that he had been faithless, careless of her happiness and occasionally really cruel. Had something happened to her?

‘I’ll make it up to her. I’ll wed her straight away. Give me another chance.’

‘I’m not often in the mind to give one chance, let alone two. Go thy gate. Thy bride’s waiting for thee in a bed of bulrushes. Oh, what a bridal bed!’

George staggered to his feet, knocking over his chair. He stumbled past Awd Molly and through the door.

‘Good night, George!’ Molly cried after him. ‘All roads lead to the Swale tonight!’

His friends heard him crashing down the stairs and slamming the outside door behind him. Awd Molly hawked and spat scornfully into the fire. Then without a word, she turned and followed George downstairs.

![]()

When the miller heard the banging on his door the following morning he knew without being told that the news was bad. Sure enough, a carter bringing oats to the mill had seen something at the edge of the River Swale. He climbed from the cart to investigate. Lying together in a muddy bed of bulrushes were George and his poor Mary. The carter called for help but it was too late; they were both drowned and cold.

Had they met? Had she drowned herself first? Had his guilt led him to follow her? Had he murdered her and then committed suicide? There were no answers. Awd Molly might have had some but she held her peace and no one dared ask her.

Dales folk say that if you are brave enough to walk by the Swale at midnight you will see them in the water sometimes; first the girl, then the man, their pale bloated bodies drifting with the flow, slowly moving closer together.

LD

M

OLLY

AND

THE

C

AUL

A lass if born in June with a caul

Will wed, hev bairns & rear ‘em all.

But a lass if born with a caul in July,

Will loose her caul & her young will die.

Every month beside luck comes with a caul

If safe put by,

If lost she may cry:

For ill luck on her will fall.

For man it’s luck – be born when he may –

It is safe be kept ye mind,

But if lost it be he’ll find

Ill-deed his lot for many a day.

(Fairfax-Blakeborough, 1923)

A baby born with a caul, or mask, over the face is lucky as long as the caul is kept safe. Such a baby will never drown and will grow up able to do many things that an ordinary person cannot – as long as they do not lose it. But the caul’s power is coveted by witches who are always trying to steal them.

Jane Herd was born with a caul of particular power. If she laid it on the Bible and spoke a name, that person was bound to come to see her shortly afterwards. Many were the strange things that she could do, but, being a churchgoing lass, she never used her caul for ill.

One day when she was using the caul she had the window open and a chance gust of wind blew it right out and away. Jane rushed to catch it but it was so light that she did not know in which direction it had been blown and so it was lost.

From that day on Jane’s luck turned. Her betrothed cancelled their marriage, she developed a nasty lump on her neck and her right knee began to hurt so badly that she could barely walk. People began to speculate as to what was causing the trouble and the consensus was that some evil person had hold of the caul and was using it to curse her.

The only person Jane could remember seeing in the street on the day her caul disappeared was Molly Cass, but she had been so far away that it seemed impossible that she could be the culprit. There was only one thing for it – she would have to consult the wise men of Bedale. Master Sadler and Thomas Spence had great names in those days as healers and solvers of uncanny problems. No doubt there was a doctor somewhere in the neighbourhood, but doctors were expensive and not really trusted by local people. No, it was the wise men that would have the answer.

Nervously Jane went to see them. They made mystic signs around the lump and the bad knee. Then they told her of certain secret ingredients she was to bring to them at midnight the following evening.

When she arrived at the appointed time, a fire of wickenwood (rowan, the sovereign against witches) had been kindled on their hearth and the ingredients she had brought were solemnly boiled together in a great pot, which she had to stir with a wickenwood rod until a thick black smoke began to rise from it. Jane was told to inhale the smoke nine times; coughing and retching she did her best. Then, still holding the rod, she had to place her other hand on the Bible and repeat the following question: ‘Has —— got ma caul?’ (Inserting the name of anyone she suspected.) After a minute Master Sadler said, ‘No, she is free!’ and Jane had to go on to name another suspect.

Name after name she suggested with no result, but the moment she mentioned Molly Cass the pot boiled over and there was such a terrible smoke and stench that they all had to run into the backyard. There they disturbed Molly herself, standing on a settle and peering through a crack in the shutters! They all three grabbed her and forced her into the smoke-filled room. She coughed and shouted and wheezed, but to save herself from suffocation she was finally forced to confess that she had the caul. Gasping she promised to return it.

Jane was not very forgiving. She and the wise men locked Molly in the stable with a wickenwood peg fastening the door so that she could not break out. The next day she was ducked nine times in the mill race.

For sure she was a queer awd lass

As mean as muck, as bold as brass.

I mean t’awd witch, awd Molly Cass

At lived nigh t’mill at Leeming.

BOUT

M

OTHER

S

HIPTON

Nidderdale

Close to the Dropping Well in Knaresborough is a small gloomy cave said to have been the birthplace and home of the famous prophetess, Mother Shipton. Both cave and well have probably been regarded as sacred for many hundreds of years, but she herself appeared on the scene much more recently, probably in the seventeenth century, when the earliest mention of her can be found in chapbooks.