On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (14 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

Chapter Eight

The Blind Men and the Elephant

The man who ranges in No Man's Land

Is dogged by shadows on either hand6

— James H. Knight-Adkin

"No Man's Land"

A Host of Observers and a Multitude of Answers

As we have examined each of the components and subcomponents of psychiatric casualty causation, we have consistently found authorities w h o would claim that their perspective of the problem represents the major or primary cause of stress in battle. Many have held that fear of death and injury was the primary cause of psychiatric casualties. Bartlett feels that "there is perhaps no general condition which is more likely to produce a large crop of nervous and mental disorders than a state of prolonged and great fatigue."

General Fergusson states that "lack of food constitutes the single biggest assault upon morale." And Murry holds that "coldness is enemy number o n e , " while Gabriel makes a powerful argument for emotional exhaustion caused by extended periods of autonomic fight-or-flight activation. Holmes, on the other hand, spends a chapter of his book convincing us of the horror of battle, and he claims that "seeing friends killed, or, almost worse, being unable T H E B L I N D M E N AND THE ELEPHANT 95

to help them when wounded, leaves enduring scars." In addition to these more obvious factors of fear, exhaustion, and horror, I have added the less obvious but vitally important factors represented by the W i n d of Hate and the Burden of Killing.

Like the blind men of the proverb, each individual feels a piece of the elephant, and the enormity of what he has found is overwhelming enough to convince each blindly groping observer that he has found the essence of the beast. But the whole beast is far more enormous and vastly more terrifying than society as a whole is prepared to believe.

It is a combination of factors that forms the beast, and it is a combination of stressors that is responsible for psychiatric casualties.

For instance, when we see incidents of mass psychiatric casualties caused by the use of gas in World W a r I, we must ask ourselves what caused the soldiers' trauma. Were they traumatized by fear and horror at the gas and the unknown aspect of death and injury that it represented? Were they traumatized by the realization that someone would hate them enough to do this horrible thing to them? Or were they simply sane men unconsciously selecting insanity in order to escape from an insane situation, sane men taking advantage of a socially and morally acceptable opportunity to cast off the burden of responsibility in combat and escape from the mutual aggression of the battlefield? Obviously, a concise and complete answer would conclude that all of these factors, and more, are responsible for the soldier's dilemma.

Forces That Impede an Understanding of the Beast

A

culture raised on R a m b o , Indiana Jones, Luke Skywalker, and James Bond wants to believe that combat and killing can be done with impunity — that we can declare someone to be the enemy and that for cause and country the soldiers will cleanly and remorselessly wipe him from the face of the earth. In many ways it is simply too painful for society to address what it does when it sends its young men off to kill other young men in distant lands.

And what is too painful to remember, we simply choose to 96 KILLING AND C O M B A T T R A U M A

forget. Glenn Gray spoke from personal experience in World War II when he wrote:

Few of us can hold on to our real selves long enough to discover the real truths about ourselves and this whirling earth to which we cling. This is especially true of men in war. The great god Mars tries to blind us when we enter his realm, and when we leave he gives us a generous cup of the waters of Lethe to drink.

Even the field of psychology seems to be ill prepared to address the guilt caused by war and the attendant moral issues. Peter Marin condemns the "inadequacy" of our psychological terminology in describing the magnitude and reality of the "pain of human conscience." As a society, he says, we seem unable to deal with moral pain or guilt. Instead it is treated as a neurosis or a pathology,

"something to escape rather than something to learn from, a disease rather than — as it may well be for the vets — an appropriate if painful response to the past." Marin goes on to note the same thing that I have in my studies, and that is that Veterans Administration psychologists are seldom willing to deal with problems of guilt; indeed, they often do not even raise the issue of what the soldier did in war. Instead they simply, as one VA psychologist put it to Marin, "treat the vet's difficulties as problems in adjustment."

Toward a Greater Understanding of the Heart of Darkness

During the American Civil War the soldier's first experience in combat was called "seeing the elephant." Today the existence of our species and of all life on this planet may depend on our not just seeing but knowing and controlling the beast called war — and the beast within each of us. No more important or vital subject for research exists, yet there is that within us that would turn away in disgust. And so the study of war has been largely left to the soldiers. But Clausewitz warned almost two hundred years ago that "it is to no purpose, it is even against one's better interest, to turn away from the consideration of the affair because the horror of its elements excites repugnance."

S E C T I O N I I I

Killing and Physical Distance:

From a Distance, You Don't Look Anything

Like a Friend

Unless he is caught up in murderous ecstasy, destroying is easier when done from a little remove. With every foot of distance there is a corresponding decrease in reality. Imagination flags and fails altogether when distances become too great. So it is that much of the mindless cruelty of recent wars has been perpetrated by warriors at a distance, who could not guess what havoc their powerful weapons were occasioning.

— Glenn Gray

The Warriors

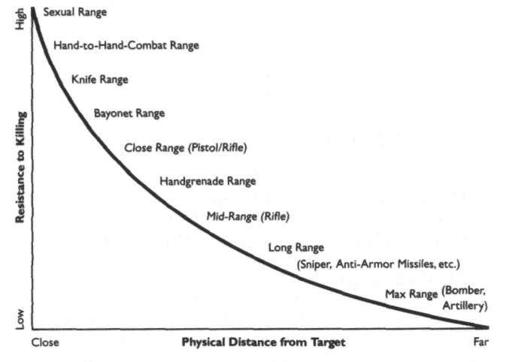

T h e link between distance and ease of aggression is not a new discovery. It has long been understood that there is a direct relationship between the empathic and physical proximity of the victim, and the resultant difficulty and trauma of the kill. This concept has fascinated and concerned soldiers, philosophers, anthropolo-gists, and psychologists alike.

At the far end of the spectrum are bombing and artillery, which are often used to illustrate the relative ease of long-range killing.

98

KILLING AND PHYSICAL DISTANCE

As we draw toward the near end of the spectrum, we begin to realize that the resistance to killing becomes increasingly more intense. This process culminates at the close end of the spectrum, when the resistance to bayoneting or stabbing becomes tremendously intense, and killing with the bare hands (through such common martial arts techniques as crushing the throat with a blow or gouging a thumb through the eye and into the brain) becomes almost unthinkable. Yet even this is not the end, as we will discover when we address the macabre region at the extreme end of the scale, where sex and killing intermingle.

In the same way that the distance relationship has been identified, so too have many observers identified the factor of emotional or empathic distance. But no one has yet attempted to dissect this factor in order to determine its components and the part they play in the killing process.

Chapter One

Distance:

A Qualitative Distinction in Death

The soldier-warrior could kill his collective enemy, which now included women and children, without ever seeing them. The cries of the wounded and dying went unheard by those who inflicted the pain. A man might slay hundreds and never see their blood flow. . . .

Less than a century after the Civil War ended, a single bomb, delivered miles above its target, would take the lives of more than 100,000 people, almost all civilians. The moral distance between this event and the tribal warrior facing a single opponent is far greater than even the thousands of years and transformations of culture that separate them. . . .

The combatants in modern warfare pitch bombs from 20,000

feet in the morning, causing untold suffering to a civilian population, and then eat hamburgers for dinner hundreds of miles away from the drop zone. The prehistoric warrior met his foe in a direct struggle of sinew, muscle, and spirit. If flesh was torn or bone broken he felt it give way under his hand. And though death was more rare than common (perhaps because he felt the pulse of life 100 KILLING AND PHYSICAL D I S T A N C E

and the nearness of death under his fingers), he also had to live his days remembering the man's eyes whose skull he crushed.

— Richard Heckler

In Search of the Warrior Spirit

Hamburg and Babylon: Examples at Extreme Ends

of the Spectrum

On July 28, 1943, the British Royal Air Force firebombed H a m -

burg. Gwynne Dyer tells us that they used the standard mixture of bombs, with

huge numbers of four-pound incendiaries to start fires on roofs and thirty-pound ones to penetrate deeper inside buildings, together with four thousand-pound high explosive bombs to blow in doors and windows over wide areas and fill the streets with craters and rubble to hinder fire-fighting equipment. But on a hot, dry summer night with good visibility, the unusually tight concentration of the bombs in a densely populated working class district created a new phenomenon in history: a firestorm.

Eventually it covered an area of about four square miles, with an air temperature at the center of eight hundred degrees Celsius and convection winds blowing inward with hurricane force. One survivor said the sound of the wind was "like the Devil laughing."

. . . Practically all the apartment blocks in the firestorm area had underground shelters, but nobody who stayed in them survived; those who were not cremated died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

But to venture into the streets was to risk being swept by the wind into the very heart of the firestorm.

Seventy thousand people died at Hamburg the night the air caught fire. They were mostly women, children, and the elderly, since those of soldiering age were generally at the front. They died horrible deaths, burning and suffocating. If bomber crew members had had to turn a flamethrower on each one of these seventy thousand women and children, or worse yet slit each of their throats, the awfulness and trauma inherent in the act would have D I S T A N C E : A QUALITATIVE D I S T I N C T I O N 101

been of such a magnitude that it simply would not have happened.

But when it is done from thousands of feet in the air, where the screams cannot be heard and the burning bodies cannot be seen, it is easy.

It seemed as though the whole of Hamburg was on fire from one end to the other and a huge column of smoke was towering well above us — and we were at 20,000 feet! Set in the darkness was a turbulent dome of bright red fire, lighted and ignited like the glowing heart of a vast brazier. I saw no streets, no outlines of buildings, only brighter fires which flared like yellow torches against a background of bright red ash. Above the city was a misty red haze. I looked down, fascinated but aghast, satisfied yet horrified.

— RAF aircrew over Hamburg, July 28, 1943

quoted in Gwynne Dyer,

War

From twenty thousand feet the killer could feel fascinated and satisfied with his work, but this is what the people on the ground were experiencing:

Mother wrapped me in wet sheets, kissed me, and said, "Run!"

I hesitated at the door. In front of me I could see only fire — everything red, like the door to a furnace. An intense heat struck me.

A burning beam fell in front of my feet. I shied back but then, when I was ready to jump over it, it was whirled away by a ghostly hand. The sheets around me acted as sails and I had the feeling that I was being carried away by the storm. I reached the front of a five-story building . . . which . . . had been bombed and burned out in a previous raid and there was not much in it for the fire to get hold of. Someone came out, grabbed me in their arms, and pulled me into the doorway.

— Traute Koch, age fifteen in 1943

quoted in Gwynne Dyer,

War

Seventy thousand died at Hamburg. Eighty thousand or so died in 1945 during a similar firebombing in Dresden. T w o hundred and twenty-five thousand died in firestorms over Tokyo as a result 102 KILLING AND PHYSICAL D I S T A N C E

of only two firebomb raids. W h e n the atomic bomb was dropped over Hiroshima, seventy thousand died. Throughout World War II bomber crews on both sides killed millions of women, children, and elderly people, no different from their own wives, children, and parents. T h e pilots, navigators, bombardiers, and gunners in these aircraft were able to bring themselves to kill these civilians primarily through application of the mental leverage provided to them by the distance factor. Intellectually, they understood the horror of what they were doing. Emotionally, the distance involved permitted them to deny it. Despite what a recent popular song might tell us, from a distance you don't look anything like a friend.

From a distance, I can deny your humanity; and from a distance, I cannot hear your screams.

Babylon

In 689 B.C. King Sennacherib of Assyria destroyed the city of Babylon:

I leveled the city and its houses from the foundations to the top, I destroyed them and consumed them with fire. I tore down and removed the outer and inner walls, the temples and the ziggurats built of brick, and dumped the rubble in the Arahtu canal. And after I had destroyed Babylon, smashed its gods and massacred its population, I tore up its soil and threw it into the Euphrates so that it was carried by the river down to the sea.

Gwynne Dyer uses this quote to point out that although more labor intensive than nuclear weapons, the physical effect on Babylon was litlle different from the effect of nuclear weapons at Hiroshima or firebombs at Dresden. Physically the effect is the same, but

psychologically

the difference is tremendous.

No personal accounts of this horror have lasted through the ages, but we can see an echo of murder on such a scale in the accounts of survivors of Nazi atrocities. In

This Way for the Gas,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Tadeusz Borowski's memoir of his experiences in a Nazi death camp, he gives us a brief glimpse of the sheer horror of such mass killing:

D I S T A N C E : A QUALITATIVE D I S T I N C T I O N 103

We climb inside [a railroad car]. In the corners amid human ex-crement and abandoned wrist-watches lie squashed, trampled infants, naked little monsters with enormous heads and bloated bellies. We carry them out like chickens, holding several in each hand.

. . . I see four . . . men lugging a corpse: a huge swollen female corpse. Cursing, dripping wet from the strain, they kick out of their way some stray children who have been running all over the ramp, howling like dogs. The men pick them up by the collars, heads, arms, and toss them inside the trucks, on top of the heaps.

The four men have trouble lifting the fat corpse onto the car, they call others for help, and all together they hoist up the mound of meat. Big swollen, puffed-up corpses are being collected from all over the ramp; on top of them are piled the invalids, the smothered, the sick, the unconscious. The heap seethes, howls, groans.

In Babylon someone had to personally hold down tens of thousands of men, women, and children, while someone else stabbed and hacked at these horrified Babylonians. O n e by one. Grandfathers struggled and wept as screaming grandchildren and daughters and sons were raped and slaughtered. Mothers and fathers writhed in their dying agony as they watched their children being raped and butchered. Again, Borowski captures a faint timeless echo of this mass murder of the innocent in a terse paragraph telling of the murder of a single lost, confused, frightened little Jewish girl: This time a little girl pushes herself halfway through the small window [of the cattle car] and, losing her balance, falls out on the gravel. Stunned, she lies still for a moment, then stands up and begins walking around in a circle, faster and faster, waving her rigid arms in the air, breathing loudly and spasmodically, whining in a faint voice. Her mind has given way . . . an S.S. man approaches calmly, his heavy boot strikes between her shoulders. She falls.

Holding her down with his foot, he draws his revolver, fires once, then again. She remains face down, kicking the gravel with her feet, until she stiffens.

104

KILLING AND PHYSICAL D I S T A N C E

Exchange the revolver for a sword, and then multiply this scene by tens of thousands, and you have the horror that was the sack of Babylon and a thousand other forgotten cities and nations.

Borowski knew that with these Jewish victims of a later-day Babylon "experienced professionals will probe into every recess of their flesh, will pull the gold from under the tongue and the diamonds from the uterus and the colon." History tells us that in Babylon and other such situations the victims were held down while their bodies were slit open to determine if they had swallowed or secreted valuables, and then they were often left to die slowly as they crawled off with their torn intestines and stomach dragging after them.

Even the Nazis usually segregated sexes and families and could seldom bring themselves to individually bayonet their victims.

They preferred machine guns upon occasion, and gas chamber showers for the really big work. T h e horror of Babylon staggers the imagination.1

The Difference

I could not visualize the horrible deaths my bombs. . . had caused here. I had no feeling of guilt. I had no feeling of accomplishment.

— J . Douglas Harvey, World War II bomber pilot, visiting rebuilt Berlin in the 1960s

quoted in Paul Fussell,

Wartime

What is the difference between what happened in Hamburg and in Babylon? There was no distinction in the results — in both, the innocent populations involved died horribly and their cities were destroyed. So what is the difference?

T h e difference is the difference between what the Nazi executioners did to the Jews and what the Allied bombardiers did to Germany and Japan. The difference is the difference between what Lieutenant Calley did to a village full of Vietnamese, and what many pilots and artillerymen did to similar Vietnamese villages.

The difference is that, emotionally, when we dwell on the butchers of Babylon or Auschwitz or My Lai, we feel revulsion at the psychotic and alien state that permitted these individuals to D I S T A N C E : A QUALITATIVE D I S T I N C T I O N

105

perform their awful deeds. We cannot understand h o w anyone could perform such inhuman atrocities on their fellow man. We call it murder, and we hunt down and prosecute the criminals responsible, be they Nazi war criminals or American war criminals.

And by prosecuting these individuals we gain peace of mind by affirming to ourselves that this is an aberration that civilized societies do not tolerate.

But when most people think of those who bombed Hamburg or Hiroshima, there is no feeling of disgust for the deed, certainly not the intensity of disgust felt for Nazi executioners. W h e n we mentally empathize with the bomber crews, when we put ourselves in their places, most cannot truly see themselves doing any different than they did. Therefore we do not judge them as criminals. We rationalize their actions and most of us have a gut feeling that we could have done what the bomber crews did, but could not ever have done what the executioners did.

W h e n we reach out with empathy in these circumstances, we also empathize with the victims. Oddly enough, very few survivors of strategic bombing in Britain and Germany suffered from long-term emotional trauma resulting from their experiences, while most of the survivors of Nazi concentration camps — and many soldiers in battle — did and continue to do so. Incredibly, yet undeniably, there is a qualitative distinction in the eyes of those w h o suffered: the survivors of Auschwitz were personally traumatized by criminals and suffered lifelong psychological damage from their experiences, whereas the survivors of Hamburg were incidental victims of an act of war and were able to put it behind them.

Glenn Gray, a trained philosopher, served in an intelligence unit in World War II that was responsible for dealing with civilians ranging from spies to Nazi collaborators to survivors of concentration camps. He understood this qualitative distinction in the manner of death:

Not the frequency of death but the manner of dying makes a qualitative difference. Death in war is commonly caused by members of my own species actively seeking my end, despite the fact that they may never have seen me and have no personal reason for enmity. It is death brought about by hostile intent rather than KILLING AND PHYSICAL D I S T A N C E

by accident or natural causes that separates war from peace so completely.

Even our legal system is established around a determination of intent. Emotionally and intellectually we can readily grasp the difference between premeditated murder and manslaughter. The distinction based on intent represents an institutionalization of our emotional responses to these situations.

The issue of relative trauma in killing situations (for both the victim and the killer) was addressed earlier. It is sufficient to say here that at some instinctive, empathic level both survivors and historical observers understand the qualitative distinction between dying in a bombing attack and dying in a concentration camp.