On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (26 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

Chapter Five

The Greatest Trap of All: To Live with That

Which Thou Hath Wrought

The Price and Process of Atrocity

The psychological trauma of living with what one has done to one's fellow man may represent the most significant toll taken by atrocity. Those who commit atrocity have made a Faustian bargain with evil. They have sold their conscience, their future, and their peace of mind for a brief, fleeting, self-destructive advantage.

Sections of this study have been devoted to examining the remarkable power of man's resistance to kill, to the psychological leverage and manipulation required to get men to kill, and to the trauma resulting from it. Once we have taken all of these things into consideration, then we can see that the psychological burden of committing atrocities must be tremendous.

But let me make it

absolutely clear

that this examination of the trauma associated with killing is in no way intended to belittle or downplay the horror and trauma of those who have suffered from atrocities. The focus here is to obtain an

understanding

of the processes associated with atrocity, an understanding that is in no way intended to slight the pain and suffering of atrocity's victims.

T H E G R E A T E S T T R A P O F ALL

223

The Cost of Compliance

. . .

The killer can be empowered by his killing, but ultimately, often years later, he may bear the emotional burden of guilt that he has buried with his acts. This guilt becomes virtually unavoidable when the killer's side has lost and must answer for its actions — which, as we have seen, is one of the reasons that forcing participation in atrocities is such a strangely effective way of motivating men in combat.

Here we see a German soldier w h o , years later, has to face the enormity of his actions:

[He] retains a stark image of the burning of some peasant huts in Russia, their owners still inside them. "We saw the children and the women with their babies and then I heard the poouff— the flame had broken through the thatched roof and there was a yellow-brown smoke column going up into the air. It didn't hit me all that much then, but when I think of it now — I slaughtered those people. I murdered them."

— John Keegan and Richard Holmes

Soldiers

The guilt and trauma of an average human being w h o is forced to murder innocent civilians don't necessarily have to wait years before they well up into revulsion and rebellion. Sometimes, the executioner cannot resist the forces that cause him to kill, but the still, small voice of humanity and guilt wins out shortly thereafter.

And if the soldier truly acknowledges the magnitude of his crime, he must rebel violently. As a World War II intelligence officer, Glenn Gray interviewed a German defector who was morally awakened by his participation in an execution: I shall always remember the face of a German soldier when he described such a drastic awakening. . . . At the time we picked him up for investigation . . . in 1944, he was fighting with the French Maquis against his own people. To my question concerning his motives for deserting to the French Resistance, he responded by describing his earlier involvement in German reprisal raids against 224

KILLING AND A T R O C I T I E S

the French. On one such raid, his unit was ordered to burn a village and allow none of the villagers to escape. . . . As he told how women and children were shot as they fled screaming from the flames of their burning homes, the soldier's face was contorted in painful fashion and he was nearly unable to breathe. It was quite clear that this extreme experience had shocked him into full awareness of his own guilt, a guilt he feared he would never atone.

At the moment of that awakening he did not have the courage or resolution to hinder the massacre, but his desertion to the Resistance soon after was evidence of a radically new course.

On rare occasions those who are commanded to execute human beings have the remarkable moral fiber necessary to stare directly into the face of the obedience-demanding authority and refuse to kill. These situations represent such a degree of moral courage that they sometimes become legendary. Precise narratives of a soldier's personal kills are usually very hard to extract in an interview, but in the case of individuals w h o refused to participate in acts that they considered to be wrong, the soldiers are usually extremely proud of their actions and are pleased to tell their story.

Earlier in this study, we saw the World War I veteran w h o took tremendous pride in "outsmarting" the army and intentionally missing while a member of a firing squad, and we saw the Contra mercenary w h o was overjoyed that he and his comrades spontane-ously decided to intentionally miss a boat full of civilians. A veteran of the Christian militia in Lebanon had several personal kills that he was quite willing to tell me about, but he also had a situation in which he was ordered to fire on a car and refused to do so. He was unsure of w h o was in the car, and he was proud to say that he actually went to the stockade rather than kill in this situation.

All of us would like to believe that we would not participate in atrocities. That we could deny our friends and leaders and even turn our weapons on them if need be. But there are profound processes involved that prevent such confrontation of peers and leaders in atrocity circumstance. T h e first involves group absolution and peer pressure.

THE GREATEST TRAP OF ALL 225

In a way, the obedience-demanding authority, the killer, and his peers are all diffusing the responsibility among themselves. The authority is protected from the trauma of, and responsibility for, killing because others do the dirty work. The killer can rationalize that the responsibility really belongs to the authority and that his guilt is diffused among everyone who stands beside him and pulls the trigger with him. This diffusion of responsibility and group absolution of guilt is the basic psychological leverage that makes all firing squads and most atrocity situations function.

Group absolution can work within a group of strangers (as in a firing-squad situation), but if an individual is bonded to the group, then peer pressure interacts with group absolution in such a way as to almost force atrocity participation. Thus it is extraordinarily difficult for a man who is bonded by links of mutual affection and interdependence to break away and openly refuse to participate in what the group is doing, even if it is killing innocent women and children.

Another powerful process that ensures compliance in atrocity situations is the impact of terrorism and self-preservation. The shock and horror of seeing

unprovoked

violent death meted out creates a deep atavistic fear in human beings. Through atrocity the oppressed population can be numbed into a learned helplessness state of submission and compliance. The effect on the atrocity-committing soldiers appears to be very similar. Human life is profoundly cheapened by these acts, and the soldier realizes that one of the lives that has been cheapened is his own.

At some level the soldier says, "There but for the grace of God go I," and he recognizes with a deep gut-level empathy that one of those screaming, twitching, flopping, bleeding, horror-struck human bodies could very easily be his.

. . .

And the Cost of Noncompliance

Glenn Gray notes what may have been one of the most remarkable refusals to participate in an atrocity in recorded history: In the Netherlands, the Dutch tell of a German soldier who was a member of an execution squad ordered to shoot innocent hostages.

226 KILLING AND A T R O C I T I E S

Suddenly he stepped out of rank and refused to participate in the execution. On the spot he was charged with treason by the officer in charge and was placed with the hostages, where he was promptly executed by his comrades. In an act the soldier has abandoned once and for all the security of the group and exposed himself to the ultimate demands of freedom. He responded in the crucial moment to the voice of conscience and was no longer driven by external commands . . . we can only guess what must have been the influence of his deed on slayers and slain. At all events, it was surely not slight, and those who hear of the episode cannot fail to be inspired.

Here, in its finest form, we see the potential for goodness that exists in all human beings. Overcoming group pressure, obedience-demanding authority, and the instinct of self-preservation, this German soldier gives us hope for mankind and makes us just a little proud to be of the same race. This, ultimately, may be the price of noncompliance for those men of conscience trapped in a group or nation that is, itself, trapped in the dead-end horror of the atrocity cycle.

The Greatest Challenge of All: To Pay the Price of Freedom

Let us set for ourselves a standard so high that it will be a glory to live up to it, and then let us live up to it and add a new laurel to the crown of America.

— Woodrow Wilson

In the same way, every soldier w h o refuses to kill in combat, secretly or openly, represents the latent potential for nobility in mankind. And yet it is a paradoxically dangerous potential if the forces of freedom and humanity must face those whose unrestrained killing is empowered by atrocities.

T h e " g o o d " that is not willing to overcome its resistance to killing in the face of an undeniable "evil" may be ultimately destined for destruction. Those w h o cherish liberty, justice, and truth must recognize that there is another force at large in this world. There is a twisted logic and power resident in the forces T H E G R E A T E S T T R A P OF ALL 227

of oppression, injustice, and deceit, but those who claim this power are trapped in a spiral of destruction and denial that must ultimately destroy them and any victims they can pull with them into the abyss.

Those w h o value individual human life and dignity must recognize from whence they draw their strength, and if they are forced to make war they must do so with as much concern for innocent lives as humanly possible. They must not be tempted or antagonized into treading the treacherous and counterproductive path of atrocities. For, as Gray put it, "their brutality made fighting the Germans much easier, whereas ours weakened the will and confused the intellect." Unless a group is prepared to totally dedicate itself to the twisted logic of atrocity, it will not gain even the shortsighted advantages of that logic, but will instead be immediately weakened and confused by its own inconsistency and hypocrisy. There are no half measures when one sells one's soul.

Atrocity — this close-range murder of the innocent and helpless — is the most repulsive aspect of war, and that which resides within man and permits him to perform these acts is the most repulsive aspect of mankind. We must not permit ourselves to be attracted to it. N o r can we, in our revulsion, ignore it. Ultimately the purpose of this section, and of this study, has been to look at this ugliest aspect of war, that we might know it, name it, and confront it.

This let us pray for, this implore:

That all base dreams thrust out at door,

We may in loftier aims excel

And, like men waking from a spell,

Grow stronger, nobler, than before,

When there is Peace.

— Austin Dobson, World War I veteran

"When There Is Peace"

S E C T I O N V I

The Killing Response Stages:

What Does It Feel Like to Kill?

Chapter One

The Killing Response Stages

What Does It Feel Like to Kill?

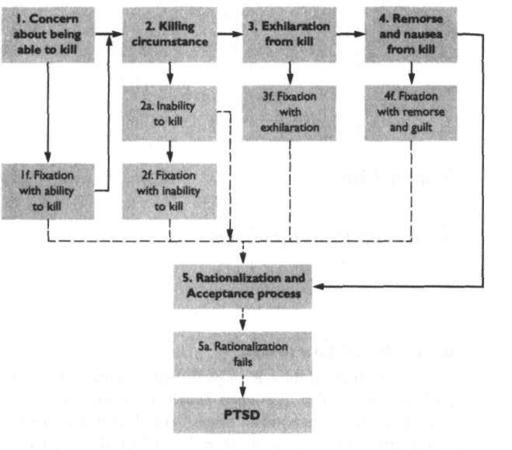

In the 1970s Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published her famous research on death which revealed that when people are dying they often go through a series of emotional stages, including denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. In the historical narratives I have read, and in my interviews with veterans over the last two decades, I have found a similar series of emotional response stages to killing in combat.

The basic response stages to killing in combat are concern about killing, the actual kill, exhilaration, remorse, and rationalization and acceptance. Like Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's famous stages in response to death and dying, these stages are generally sequential but not necessarily universal. Thus, some individuals may skip certain stages, or blend them, or pass through them so fleetingly that they do not even acknowledge their presence.

Many veterans have told me that this process is similar to — but

much

more powerful than — that experienced by many first-time deer hunters: concern over the possibility of getting buck fever (i.e., failing to fire when an opportunity arises); the actual kill, occurring almost without thinking; the exhilaration and self-praise after a kill; brief remorse and revulsion (many lifelong woodsmen still become ill while gutting and cleaning a deer). And finally

232 T H E K I L L I N G R E S P O N S E S T A G E S

The Killing Response Stages

t h e a c c e p t a n c e a n d rationalization process — w h i c h in this case is c o m p l e t e d b y eating t h e g a m e a n d h o n o r i n g its t r o p h y .

T h e processes m a y b e similar, b u t t h e e m o t i o n a l i m p a c t o f these stages a n d t h e m a g n i t u d e a n d intensity o f t h e guilt i n v o l v e d i n killing h u m a n beings are significantly different.1

T h e C o n c e r n S t a g e : " H o w A m I G o i n g t o D o ? "

US Marine Sergeant William Rogel summed up the mixture of emotions. "A n e w m a n . . . has t w o great fears. O n e is — it's probably an overriding fear — h o w am I going to do? — am I going to show the white feather? Am I going to be a coward, or am I going to be able to do my job? And of course the other is the c o m m o n fear, am I going to survive or get killed or w o u n d e d ? "

— Richard Holmes

Acts of War

T H E KILLING R E S P O N S E STAGES 233

Holmes's research indicates that one of the soldier's first emotional responses to killing is a concern as to whether, at the moment of truth, he will be able to kill the enemy or will "freeze u p " and

"let his buddies d o w n . " All of my interviews and research verify that these are deep and sincere concerns that exist on the part of most soldiers, and it must be remembered that only 15 to 20

percent of U.S. World W a r II riflemen went beyond this first stage.

T o o much concern and fear can result in fixation, resulting in an obsession with killing on the part of the soldier.2 This can also be seen in peacetime psychopathologies when individuals become fixated or obsessed with killing. In soldiers — and in individuals fixated with killing in peacetime — this fixation often comes to a conclusion through step two of the process: killing. If a killing circumstance never arises, individuals may continue to feed their fixation by living in a fantasy world of Hollywood-inspired killing, or they may resolve their fixation through the final stage, rationalization and acceptance.

The Killing Stage: "Without Even Thinking"

Two shots. Bam-bam. Just like we had been trained in "quick kill." When I killed, I did it just like that. Just like I'd been trained.

Without even thinking.

— Bob, Vietnam veteran

Usually killing in combat is completed in the heat of the moment, and for the modern, properly conditioned soldier, killing in such a circumstance is most often completed reflexively, without conscious thought. It is as though a human being is a weapon. Cocking and taking the safety catch off of this weapon is a complex process, but once it

is

off the actual pulling of the trigger is fast and simple.

Being unable to kill is a very common experience. If on the battlefield the soldier finds himself unable to kill, he can either begin to rationalize what has occurred, or he can become fixated and traumatized by his inability to kill.

234 T H E KILLING R E S P O N S E STAGES

The Exhilaration Stage: "I Had a Feeling of the Most

Intense Satisfaction"

Combat Addiction . . . is caused when, during a firefight, the body releases a large amount of adrenaline into your system and you get what is referred to as a "combat high." This combat high is like getting an injection of morphine — you float around, laughing, joking, having a great time, totally oblivious to the dangers around you. The experience is very intense if you live to tell about it.

Problems arise when you begin to want another fix of combat, and another, and another and, before you know it, you're hooked.

As with heroin or cocaine addiction, combat addiction will surely get you killed. And like any addict, you get desperate and will do anything to get your fix.

—Jack Thompson

"Hidden Enemies"

Jack Thompson, a veteran of close combat in several wars, warned of the dangers of combat addiction. T h e adrenaline of combat can be greatly increased by another high: the high of killing. What hunter or marksman has not felt a thrill of pleasure and satisfaction upon dropping his target? In combat this thrill can be greatly magnified and can be especially prevalent when the kill is c o m -

pleted at medium to long range.

Fighter pilots, by their nature, and due to the long range of their kills, appear to be particularly susceptible to such killing addiction. Or might it just be more socially acceptable for pilots to speak of it? Whatever the case, many do speak of experiencing such emotions. O n e fighter pilot told Lord Moran: Once you've shot down two or three [planes] the effect is terrific and you'll go on till you're killed. It's love of the sport rather than sense of duty that makes you go on.

And J. A. Kent writes of a World War II fighter pilot's "wildly excited voice on the radio yelling [as he completes an aerial combat kill]: 'Christ! He's coming to pieces, there are bits flying off everywhere. Boy! What a sight!'"

THE KILLING RESPONSE STAGES 235

On the ground, too, this exhilaration can take place. In a previous section we noted young Field Marshal Slim's classic response to a World War I personal kill. "I suppose it is brutal," he wrote,

"but I had a feeling of the most intense satisfaction as the wretched Turk went spinning down." I have chosen to name this the exhilaration phase because its most intense or extreme form seems to manifest itself as exhilaration, but many veterans echo Slim and call it simply "satisfaction."

The exhilaration felt in this stage can be seen in this narrative by an American tank commander describing to Holmes his intense exhilaration as he first gunned down German soldiers: "The excitement was just fantastic . . . the exhilaration, after all the years of training, the tremendous feeling of lift, of excitement, of exhilaration, it was like the first time you go deer hunting."

For some combatants the lure of exhilaration may become more than a passing occurrence. A few may become fixated in the exhilaration stage and never truly feel remorse. For pilots and snipers, who are assisted by physical distance, this fixation appears to be relatively common. The image of the aggressive pilot who loves what he does (killing) is a part of the twentieth-century heritage. But those who kill completely without remorse at close range are another situation entirely.3

Here again we are beginning to explore the region of Swank and Marchand's 2 percent "aggressive psychopaths" (a term that today has evolved into "sociopaths"), who appear to have never developed any sense of responsibility and guilt. As we saw in a previous section, this characteristic, which I prefer to call aggressive personality (a sociopath has the capacity for aggression without any empathy for his fellow human beings; the aggressive personality has the capacity for aggression but may or may not have a capacity for empathy), is probably a matter of degrees rather than a simple categorization.

Those who are truly fixated with the exhilaration of killing either are extremely rare or simply don't talk about it much. A combination of both of these factors is responsible for the lack of individuals (outside of fighter pilots) who like to write about or dwell upon the satisfaction they derived from killing. There is a 236

T H E KILLING R E S P O N S E STAGES

strong social stigma against saying that one enjoyed killing in combat. Thus it is extraordinary to find an individual expressing emotions like these communicated by R. B. Anderson in "Parting Shot: Vietnam Was Fun(?)":

Twenty years too late, America has discovered its Vietnam veterans. . . . Well-intentioned souls now offer me their sympathy and tell me how horrible it all must have been.

The fact is, it was fun. Granted, I was lucky enough to come back in one piece. And granted, I was young, dumb, and wilder than a buck Indian. And granted I may be looking back through rose-colored glasses.

But it was great fun

[Anderson's emphasis]. It was so great I even went back for a second helping. Think about it.

. . . Where else could you divide your time between hunting the ultimate big game and partying at "the ville"? Where else could you sit on the side of a hill and watch an air strike destroy a regimental base camp? . . .

Sure there were tough times and there were sad times. But Vietnam is the benchmark of all my experiences. The remainder of my life has been spent hanging around the military trying to recapture some of that old-time feeling. In combat I was a respected man among men. I lived on life's edge and did the most manly thing in the world: I was a warrior in war.

The only person you can discuss these things with is another veteran. Only someone who has seen combat can understand the deep fraternity of the brotherhood of war. Only a veteran can know about the thrill of the kill and the terrible bitterness of losing a friend who is closer to you than your own family.

This narrative gives us a remarkable insight into what there is about combat that can make it addicting to some. Many veterans might disagree strongly with this representation of the war, and some might quietly agree, but few would have this author's courageous openness.4

The Remorse Stage: A Collage of Pain and Horror

We have previously observed the tremendous and intense remorse and revulsion associated with a close-range kill: T H E KILLING R E S P O N S E STAGES 237

. . . my experience, was one of revulsion and disgust. . . . I dropped my weapon and cried. . . . There was so much blood . . . I vomited. . . . And I cried. . . . I felt remorse and shame. I can remember whispering foolishly, "I'm sorry" and then just throwing up.

We have seen all of these quotes before, and this collage of pain and horror speaks for itself. Some veterans feel that it is rooted in a sense of identification or an empathy for the humanity of their victim. Some are psychologically overwhelmed by these emotions, and they often become determined never to kill again and thereby become incapable of further combat. But while most modern veterans

have

experienced powerful emotions at this stage, they tend to deny their emotions, becoming cold and hard inside — thus making subsequent killing much easier.

Whether the killer denies his remorse, deals with it, or is overwhelmed by it, it is nevertheless almost always there. T h e killer's remorse is real, it is common, it is intense, and it is something that he must deal with for the rest of his life.

The Rationalization and Acceptance Stage: "It T o o k All the

Rationalization I Could Muster"

The next personal-kill response stage is a lifelong process in which the killer attempts to rationalize and accept what he has done.

This process may never truly be completed. The killer never completely leaves all remorse and guilt behind, but he can usually come to accept that what he has done was necessary and right.

This narrative by John Foster reveals some of the rationalization that can take place immediately after the kill: It was like a volleyball game, he fired, I fired, he fired, I fired. My serve — I emptied the rest of the magazine into him. The rifle slipped from his hands and he just fell over. .. .

It sure wasn't like playing army as a kid. We used to shoot each other for hours. There was always a lot of screaming and yelling.

After getting shot, it was mandatory that you writhe around on the ground.

. . . I rolled the body over. When the body came to rest, my eyes riveted on his face. Part of his cheek was gone, along with 238 T H E KILLING R E S P O N S E STAGES

his nose and right eye. The rest of his face was a mixture of dirt and blood. His lips were pulled back and his teeth were clinched.