One Hundred and One Nights (9780316191913) (16 page)

Read One Hundred and One Nights (9780316191913) Online

Authors: Benjamin Buchholz

“I will sit in the courtroom every day. I’m looking forward to seeing her.”

“You’re crazy.”

“I know,” I said.

“She’s crazy,” he said.

“I know.”

He laughed, saying, “Guess you’re perfect for each other.”

I skipped visiting Annie just once. Once only.

“You didn’t come yesterday,” said the desk sergeant when I appeared the following day, regular as usual.

“No,” I said. “My brother contacted me from Baghdad to tell me my father is dead. I haven’t spoken with my brother in a decade and he calls with such news…”

“That’s too bad,” said the sergeant.

“Which part?” I asked.

“All of it,” he said. “But especially the part about you missing your visit. Your girl, Mrs. Dillon, she has impeccable timing. She was waiting for you, all prettied up in her orange jail suit, and you didn’t show.”

“What?”

“First time in how long—a hundred days? She said she knew you were just like every other man. Said you made a good show of being faithful for a while but in the end, you weren’t there. Just like us all, that’s what she said,” the sergeant said, rolling his eyes. “She also said to tell you she thinks it’s yours.”

“What’s mine?”

“The child,” he said. “She’s just starting to show.”

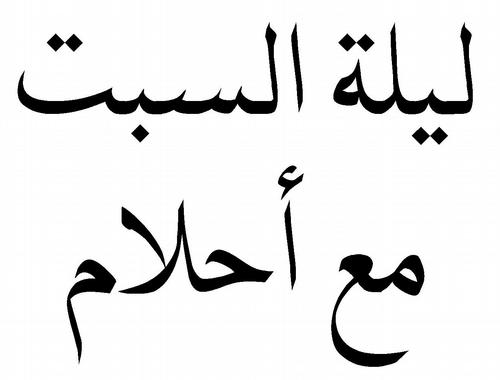

LAYLA FIRST VISITS MY

dreams tonight, like most dreams hereafter. She takes on two lives for me, the life of the living young earthly rag-clothed girl with her sudden appearances and disappearances, her improprieties, her penetrating questions; and the life of the girl who lives increasingly in my imagination and my dreams. Perhaps these two halves of her correspond to the two halves of me, the dead and the alive, the halves that fight for control of me and drive me to the absolution of my whiskey. Perhaps there is no Layla. Perhaps I just desire her so sharply that I have created all her spark and aura, like a man walking out of a desert who has been so long without water that even the idea of water pains him.

I doubt her.

My doubt settles into me so that, as I stare at my kitchen wall and drink myself to sleep, I cannot really distinguish what has been real and what has not. From a place of mild euphoric drunkenness I settle into a state of mild euphoric sleep with such ease and such a slight leveling of consciousness that sleeping and waking are difficult to tell one from the other. I have on my table in front of me the cassette recorder containing the captured sound of the

Close Encounters

song. I have these two boxes from my last two visits with Seyyed Abdullah. The cassette recorder remains mute. It occupies a space exactly in the middle between the two identical brown boxes: brown paper, brown tape, very little written on the exterior. I arrange them on my bare kitchen table: box one, box two. I move them from side to side. I shift them. I lift box one. I lift box two. I put them down at different angles and at varying distances from the cassette recorder. As I lift them, I imagine they would be of equal weight if I had not already consumed half the bottle from the first box on previous nights.

A fear similar to that which prevents me from playing the tape-recorded song prevents me from opening the second of the two boxes. I don’t want to see what is inside. Surely it contains something other than a bottle of whiskey. Surely it hides within it some sort of electronic equipment, stuff whose presence a mobile-phone salesman just might be able to justify, assembled or disassembled, in his home if police forces or the Americans raid him.

I ignore this second box, just as I ignore my doubts about Layla. I leave the box unopened on the table, orbiting the tape recorder at the same respectful distance as the torn-open whiskey box. Then I take down from the shelf above my kitchen sink the jack-in-the-box that has stared at me, so brightly colored, and kept me company through the long nights all this time since I first moved to Safwan. As I remove the toy from its place on my shelf, its head bobs and dances, giving it a moving, lifelike feeling in my hands.

Although the jack-in-the-box is in perfect condition, I spend the remainder of my evening breaking it down into its component parts, screw by screw, spring by spring, lever by lever, wheel by wheel, gear by gear, even stripping from the body of the jack the patched and polka-dotted clothing the wooden clown-faced figure wears. I peel carnival-colored stickers from the outside of the box, leaving a spiderweb pattern of glue over the blue surface of the four sides. I organize the parts in rows and files. I drink a finger of whiskey after each part I disassemble. As the whiskey burns in my throat, I place the parts in what I deem to be the correct astrological relationship to other objects on the table: hidden ellipses and orbits, constellations and zodiacal shapes emerging.

This is how the last half of the bottle from the first box disappears. This is how I put myself to sleep, face falling to rest in the crook of my arm, sprawling on the table, surrounded by a plethora of jack-in-the-box pieces that might mean more in their tea-leaf configuration than ever they had in their finished, assembled whole.

Frequently now, Layla arrives in my dreams by standing in that familiar place outside my shack, the highway behind her, the late sunlight’s long shadows crisscrossing the ground around her. I cannot tell, in dream-sight, whether her feet touch the shadowed ground, whether she has feet at all, whether her feet

are

shadow, part of the greater shadow that falls on the silently spinning and aging world. Often she arrives this way, but not tonight, not on the first night of our nights together. This night she comes through the kitchen door. I lift my head from the organized disassembly around me. I look at her. Outside the door—which leads to an interior courtyard, where I have not yet planted any flowers, not yet cultivated any fruit trees, not yet caused a fountain to flow so that it might provide lovely watery music, like the fountain in Ulayya’s court—outside this door the sun shines as though it were day. Layla’s ghostly body wafts between the sun and the place where I stand, shadowing the light. I think, as on the day of the sandstorm, I have slept a long while. I think I am waking into day-lit reality when, actually, the light of the day is itself nothing more than a dream; around me, in the real world, everything broods darkly and silently, perfect for dreaming.

Layla walks toward me.

Still she has the

abaya

and

hijab

she recently wore in the market, but she has folded and draped them over one of her arms, as if she just removed from herself all marks of womanhood. I look behind her. Against one wall of my empty inner courtyard, I see her unicycle leaning. I can plainly read a set of hieroglyphics embossed on its spokes and pedals. I can read them even from so far away, but I do not know what they say. I fear it is something revelatory: birds’ heads and hyenas and feathers, prayers full of snakes and moons and such things as should never have been created under heaven. I see little details of Layla that contradict my idea of ghostliness. For instance, she has been sweating. What ghost sweats? Also, her hair is matted to her head and she appears breathless, winded. I blame her speechlessness on the effort required to recover her breath after her unicycle journey. I am sure she will talk with me very soon. I am sure her stunning quiet is due more to her breathless condition than to any inborn, dream-borne inability to speak.

I wait for her to speak.

I look at her.

She looks at me.

She doesn’t speak.

How can a man’s mind, in his dreams, give voice to the very randomness of the childlike utterances that make a girl such as Layla magical? It is impossible. It is impossible for my mind to invent such magic and grace and serendipity. But I don’t realize the dilemma, not while I dream. And, at last, after holding out as long as I can, I blink.

The blink transfigures my dream. Now I stand on the shore of Lake Michigan, a Chicago night with snow drifting down through cityscape lights. Layla is in the snow with me. She wears her pink snowsuit, her pink mittens, her pink winter hat with the image of her bird-bone anklet embroidered in black thread on the folded brim. She bends, picks up a handful of snow, raises it level with her eyes, and lets it fall from the soft round confines of her mittens. It is fresh snow, light and fluffy, and it billows around her as it falls. Behind her, the skyscraper lights, bluish and bright in the night sky, catch the swirling snow and make it shine like so many weightless and migratory diamonds.

Layla runs toward the water, the black flat surface of the great cold lake. She steps into the water, puts one hand to her face, and, in a gesture far too human for the dream state, plugs her nose with her mittened fingers. Then she kneels, slips under the surface, and disappears from me, ghosting away into the depths like a blue-eyed, black-haired fish. I take off my baseball cap, the Cubs cap, cursed as it is, and hold it over my heart until the ripples from her disappearance themselves disappear.

Yet the dream continues. Again Layla stands in the doorway of my house. Her blue eyes, strange in the southern Iraqi desert, stare into me. She does not approach me but, as she stares at me, I know she sees the parts of the jack-in-the-box scattered in their highly organized symbolic Cracker Jack system. She begins to decrypt the pattern of the disassembled parts. She speaks words as she decodes, but her words come out in hieroglyphics, bird-headed and jackal-headed, feather-light and golden, each surrounded by a cartouche. With staff and rod and wheat and linen they rise up in the air between us. She pleads with me to catch them, corner them, contain them, document them, translate them, understand them. But I am no fool. I know that the mere act of reaching for such things will change them forever. I know that the force of reaching will disrupt them in their flight, ground them, strip them of their marrow. I let them rise and fall and waft where they will until I hear a knocking noise.

I wake.

I look around me, hoping to see Layla still standing in my kitchen. Perhaps she has made me breakfast. Perhaps she has convinced Annie to come to the visitation window when, pathetically, I next go to the jail and wait for her to show herself. Perhaps we can all be together, all three of us—Annie and Layla and me—if only in a dream.

But, awake, I see Layla nowhere around me.

The knocking on my door continues. I rise from the kitchen table, straighten my

dishdasha

over my legs, and go to the door.

* * *

The one day I missed visiting Annie was the day that Yasin called me. Over the echoing long-distance line, the connection between Baghdad and Chicago, he told me to come back to Iraq.

I froze.

I had thought I would never hear from him again. Truthfully, I thought he had died in the war against Iran. My first instinct was that the phone line, like black-magic voodoo, had transported me, linked me, to a world of spirits, to a hell.

Even after I realized it was Yasin, a living man, I still felt uncomfortable about him contacting me, with what seemed like uncanny ease, across half the world—even after I had just moved into a new apartment, even after I had changed my job, even after I had quit my other life so that I might give Bashar and Nadia some space. I certainly didn’t feel happy about it, hearing from him.

After a moment I said, “I thought you were dead. We all thought you were dead.”

“I’m not. But Father is.”

“He called three months ago. I knew from the sound of his voice that he wouldn’t live much longer.”

“He went out like Abdel Hakim Amer,” said my brother.

“Suicide, then?”

My brother’s voice took on a hint of menacing secrecy, saying: “Many people have doubts about Abdel Amer.”

“And you?”

“I’m alive.”

“Alhamdulillah,”

I said.

“I work for the president.”

“Saddam?”

“Yes.”

“Doing what?”

“Whatever he wants me to do.”

My new apartment, the apartment I chose to hide from Bashar and from Nadia, was a loft midway up a twelve-story renovated factory building in Wrigleyville. From its bank of big plate-glass windows I could see directly into the far upper-deck seats of the baseball park. I paced to within an arm’s reach of the window and leaned the weight of my body against my outstretched arm, my hand pressing flat on the cold, thick glass. A ring of frost formed on the outside of the window in a halo around the heat of my fingers so that when, a moment later, I took my hand away, a negative imprint remained. The Cubs weren’t playing. It was February, not yet even spring training. Snow covered the field. Snow covered the folded-up stadium seats. The dark amphitheater of the stadium seemed to me like a heroic temple whose god had abandoned it.

“We want you to work for us.”

“We who?”

“Iraq.”

“Iraq needs a doctor?”

“Saddam needs better information on America.”

“No,” I said.

“Don’t say no. Not yet. Come home for father’s funeral next week.”

“No,” I said again, thinking of Annie in her jail cell.

“Don’t say no so quickly,” my brother told me. “I’ll call you tomorrow for your answer and then we’ll arrange a plane ticket to Baghdad. We’ll be able to speak in more detail.”

I said no again but Yasin had already hung up the line.

I couldn’t go to the jail to see Annie, to not-see Annie, as was usual—not after such news, so many things all at once. The well-established order of my world had been rocked: my father was dead, my brother was alive, and Saddam wanted me to spy on America. That’s why I skipped that one day out of all those hundred days—the day when, according to the desk sergeant, Annie actually came out from her cell to visit me.