One Hundred and One Nights (9780316191913) (20 page)

Read One Hundred and One Nights (9780316191913) Online

Authors: Benjamin Buchholz

“I accept your offer,” I say, my face regaining some of its color and warmth. “I need some for my house, some for my friends. How can a man host men in his home without the trappings a good host must provide? And these things are so difficult to obtain for any but the most well connected of hosts, impossible for a man like me, who has no connections whatsoever!”

He laughs, Ali, suspecting me to be anything but unconnected. He knows that he and Seyyed Abdullah are most connected among the citizens of Safwan. But he must guess that the two of them are only temporarily more connected than me. Once I get myself grounded, once I reestablish myself, he thinks I will begin calling in favors from all the friends of a former life.

I could make those connections if I wanted. These men know of my education abroad. They know my past jobs in Iraq. If Bashar has indeed spoken of the days in the Green Zone after the first successes, the heady successes of the Americans’ second invasion, then they know I can move in circles at the very center of power. I was here on a dream and with something that was, truly, a Greater Purpose: to make a new and better Iraq. Nor would Bashar have forgotten to tell them of the Chicago where he and I studied and worked together. Bashar, you secret-keeper! They suspect a grand design here, a grand design from a man whose biggest design has failed amid the divisive conflicts of our new civil war.

Indeed, I could reopen the connections if I wanted. I could reopen them in service of an idea more worthwhile to these townsfolk than the abstract concepts of peace and national rebirth. I could reopen my contacts in the pursuit of profit, a life of profit, a life spent making myself and Ali’s daughter obscenely rich, a life smuggling, sneaking things of value into Iraq. Such an idea would fit perfectly with Ali ash-Shareefi’s own businesses. I presume he intends for us to merge commercial forces; mobile-phone sales are just a preliminary to an empire of sales and smuggling. We will be poised at the forefront when the economy recovers, when Baghdad and Basra and Mosul become metropolitan once more and desire shipment through the border of Kuwait all the electronics and all the comforts the rest of the world now possesses.

Ali then speaks again, this time to all the assembled cousins and uncles.

“A man from the north, this soon-to-be son-in-law of mine, he will not mind viewing his bride a little more openly,” he says.

Not waiting for my response, he claps his hands together. Ulayya immediately enters from the women’s quarters, bringing with her a tray of

halwa

and tea. She sets the tray in front of her father. Ali has partaken of enough liquor from his silver flask to color his thin face red, to make him chuckle proudly at the sight of his daughter before him. He allows me to look at Ulayya for a moment, though she is veiled in a colorful gauze headpiece, blue and red and gold, and though she keeps her eyes modestly averted through the long moment of her time in the room. She knows I am present and she knows where at the table I sit, though she is careful not to look at me directly.

Ali nudges my present, my little

shabka,

toward Ulayya across the low table.

“A gift from your betrothed,” he says to her.

She takes the package and leaves the room, smiling just a little as she steps through the sheathing curtains of the doorway and returns with her prize to the gathering of women in the rooms adjacent to Ali’s

diwaniya.

I am afraid I will disappoint Ali ash-Shareefi by bringing the war here to this almost-quiet town, to his almost-quiet family, which still mourns the loss of two sons and the loss of Ulayya’s first husband, among the many men Safwan lost. I am afraid I will disappoint them, yet I am also intensely interested to know how Ulayya receives her gift. It has been a long while since I courted a woman. Her presence in the room has left my head feeling light and my heart feeling heavy.

* * *

Often during those evening parties in Baghdad, whether on the lawns of our houses or in more formal settings—dinners, banquets, balls—I saw Nadia with Bashar. Like Ulayya, despite the effects of children, Nadia retained a beautiful figure, slim and curvingly elegant. The liberation of Western clothing, Western style, suited her. She wore low-cut evening dresses. She wore stiletto heels. She wore diamonds

—

faux or real, I never could tell

—

in her hair and on her fingers and around her neck. The only element of style she retained from her upbringing in Baghdad was a preference for the heavy application of kohl around her eyes. This, combined with her darkness—the raw-honey color of her skin, the obsidian shimmer of her hair—contrasted markedly with the few other women in attendance at these parties, most of them female British and American officers or ambassadorial staff.

Nadia flaunted this beauty in front of me as if to say, “See what you have thrown away.”

I was immune to her hints at first.

It was natural, I thought, for her to gravitate toward me during these parties when Bashar found himself occupied by some deep and laborious discussion, expounding upon plans to accredit Baghdad Medical City as a research institute, plans to build factories for pharmaceuticals in some city or another, plans to start a medical scholarship program similar to the one that had launched his career and mine.

Nadia and I knew each other better than we knew the other people at those parties. What was more natural for her than to seek my company when Bashar wasn’t available? Thirteen years had passed since she slapped me in the doorway of Bashar’s apartment, thirteen years for her to forget her anger.

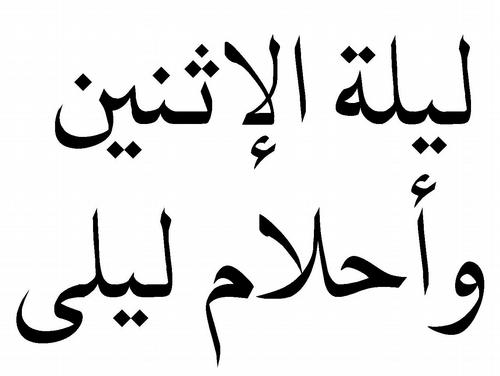

LAYLA VISITS ME IN

my dreams tonight, like most nights now. I drink a little from my bottle when, at last, I am alone. But I’m weary. By drinking I only mean to relax myself so that my face-down sleep on the bare dining-room table comes quickly and easily. The passage from wakefulness to sleep and from sleep to dream happens almost reflexively.

Just as my dreams begin, Layla appears.

She stands in shadow under the awning of my little store, my shack, as the golden sunset reflects against the pillars of the overpass where the highway from Basra to Kuwait and the even larger highway from the port of Umm Qasr to Baghdad intersect. She is wearing the gift she gave me. She is wearing it as if in the moment I opened her little boxed and flowered present—quickly, between the time when I first arrived home after Ali’s party and when Abd al-Rahim knocked on my door—I somehow gave the gift back to her, reflected it onto her in the odd logic of a dream. It is a length of blue silk, exactly like the length of silk Abd al-Rahim bought for Ulayya on my behalf, exactly the same thing as my first gift to Ulayya. Layla wears it wrapped around her head, as a scarf. In the dream it shimmers like water. It

is

water, flowing, blue, ebbing, encircling her head. It is a river, a lake, a sky, a field of budding blue lavender rippled by breezes. It is all these things in rapid succession, shifting and shimmering.

Layla spins in a slow circle as the watersilk on her head ripples with her movement. Not far from her, perhaps three meters away, Abd al-Rahim also enters the dream. He does not understand me when I tell him to remove the sky from Layla’s head so that I might see her more clearly. I don’t want any shimmering distractions. Abd al-Rahim does not understand. He doesn’t have any distractions. Maybe he doesn’t have any shimmering, either. Maybe that is why he wears polished shoes and fancy clothes and dark sunglasses: to hide the fact that he doesn’t shimmer.

“Remove it,” I say to him. “Remove that slice of fallen sky, that shimmer. Unwrap it, untie it. Use something other than a hammer. Use something other than a garden rake.”

But despite my protests, Abd al-Rahim will come no closer to Layla. He is, in fact, located on the very edge of the steel-black lake. He keeps his hands folded in front of him, looking very steadfast. He comes no closer to Layla, and I find myself irritated with him, irritated at his optimism, the way he smiles behind his impossible sunglasses, his snazzy shoes.

I say, “War isn’t something distant and oblivious and political.”

The words feel like a statement of genius. I tell myself to remember them when I wake, as if the morphing, thrown-together statement of a dream will have even the most superficial resemblance to the grammar of living. I know I am saying something important, inventing something important, so I pay very close attention to myself as I lecture Abd al-Rahim and the spinning shining image of Layla, who stands between us.

“War really isn’t news,” I say. “Nothing is news. Nothing is rhinoceros big and quicksandy and compelling, as the newspapers will have you believe. At all levels, everything, really, incidents famous or infamous, they all resolve like chocolate into a warm windowsill until they are just nuts and nougat and a wrapper fluttering in the broken air-conditioner vent. Nuts and nougats with real lives, jobs, loves, loving the caramel especially, especially when it sticks to the teeth and tongue, hobbies, quirks, fascinations. War is not big speeches and credos. It is man and man and woman and woman and child, oblivious to everything except the basics of joy and hunger and thirst and inquiry, oblivious to everything except nougat. These things can hurt, death and love and loss, but they aren’t political until someone uses them politically.”

That is my speech. Begins well, ends well. I’m not sure why all the candy enters the middle, the muddy part. Maybe I am getting hungry in my sleep. Maybe this is just my waking mind now, trying to capture both the order and the entropy of such a dream. What, anyway, does Abd al-Rahim know of war? Why does he stand on the lakeshore with his hands folded, when the sky in Layla’s hair needs rearranging? A pigtail, perhaps, fastened in the back by jack-in-the-box springs. I pluck one as I sleep from the spiraling snow between where I stand and the skyscraper lights that loom over the black lake water. I pluck a spring or a gear or a disassembled ticktock and use it to tie the scarf of the silken sky to Layla’s hair.

When, earlier tonight, I returned from Ali’s dinner, Abd al-Rahim wasn’t yet at my house. I expected him there, waiting like a dog on my doorstep, a dog who has found his way home. He shows up only five minutes later, so that I have but a minute or two to settle into my house, remove my

ghalabia,

wet my throat to tamp down the dust of the journey across town, and unwrap Layla’s present. When he knocks I shove Layla’s gift into one of the unfinished cabinets in the kitchen. I have those five minutes alone. Then, when he leaves, I drink my exhausted mind into this dream. In between, during the several hours of our time together, Abd al-Rahim and I begin our work building bombs.

“Put it together,” I say to him after I am done showing him the various empty rooms of my house.

He had indeed noticed the chaos in my dining room the first time he passed it, but we’ve moved quickly from room to room until, at last, we return to the table. He raises an eyebrow at me, questioning the significance of the brightly colored bits of jack-in-the-box.

“Put it together,” I say once more.

“Put what together?” he says.

“It’s a jack-in-the-box.”

With my forearm sweeping the table, I shove the parts toward him. I pass him a screwdriver, a hammer, forceps, a retractor, some glue, a blowtorch. Everything he should need.

“I don’t understand,” he says. “A jack-in-the-box?”

“Show me—

wax on, wax off,

” I say, a reference so foreign to Abd al-Rahim that he stares at me until I take a menacing half step toward him with a pair of pliers raised in my hand. I am surprised at my action. I haven’t done anything physically threatening or even physically spirited since leaving Baghdad, nothing except for the anticlimactic firing of Mahmoud’s ammunitionless Kalashnikov.

Likewise, I am surprised at how Abd al-Rahim reacts. A young man like him should hold his ground. He should challenge me, but he doesn’t. There is a moment of hesitation, as though he gathers his strength or his will to attack me. I brace myself. But then I see him change his mind. His shoulders slump. He sits, very quickly, hands folded in front of him. After another moment passes, as I glower above him with my raised and clicking pliers, he begins pushing the various pieces of jack-in-the-box around the table, trying to determine for himself which piece to select first in his effort at reassembly.

I watch him for a long while. I watch him struggle. I watch him choose the wrong piece, the wrong spring, the wrong ratchet or lever. I see him forget things. I notice him disassembling what he has already assembled, fixing it time and again until it is closer and closer to correct. It is a good exercise for him.

But eventually, I tire of watching him.

The jack-in-the-box is usually my cure for boredom. I tear it apart. I build it anew. I tear it apart again. But now I have no such recourse. Abd al-Rahim must have it all to himself. He must practice upon it. I am forced, at last, to open the new brown-paper package. I cut the tape, lift the flaps, and look at the contents from afar before positioning everything in neat rows in front of me. I inspect the items. I turn them this way and that way, feeling their heft and shine and danger. Then I begin to put them together. For the next two or three hours a bit of competition emerges between Abd al-Rahim and me. Both of us seem to need the screwdriver at the very same instant, then the shears at the very same instant, then the spool of wire, the tape, the glue. Our hands reach, our eyes meet, we scrabble over the table to be the first to lay hands on each necessary item. We use our hard-won tools longer than required, just to goad the other into an anger of impatience. When we are at last done, a vaguely jack-in-the-box-shaped object rests on his end of the table, and, on my end, there is a fully assembled bomb.

Abd al-Rahim adjusts the jack-in-the-box on the table so that it faces me. He turns the crank. The gears connect, the springs groan, the jack-in-the-box emerges, but only slowly and only lopsidedly, as though it is drugged. It does not spring forth. Abd al-Rahim shrugs.

“Not bad,” he says. “Not bad for a first try.”

I do not turn the crank on my bomb.

* * *

The day Bashar and his family fled Baghdad, he left me a note on official ministerial letterhead. It read:

The vendors of Al-Kindi Street have closed their shops. The parks we thought would fill with musicians and lovers contain only roving bands of teenagers who pretend their crimes are justified by jihad. This is no life for my family. We are leaving. Perhaps somewhere far from here I will open a restaurant or a bowling alley! I wish you and yours the best of luck here. You are braver than me to persevere.

Politically, this message was something I expected. Bashar had begun transferring more and more of his job responsibilities to me and, with the incoming cabinet, newly formed after Iraq’s first free elections, we saw our duties decreasing. Ministers from Sunni families like ours were pushed aside, despite our skills and knowledge. The Shia ruled in the government and on the streets of Baghdad, both by virtue of their numbers and through violence, neighborhood against neighborhood, with the result that most Sunni families left the capital for Anbar Province to the west.

Nor was Bashar’s sudden departure emotionally unexpected. Nadia had become more and more daring in her temptations. She would wait for Bashar to step away from us. She would wait for him to leave, and then she would approach me, pretend to make conversation with me, but really only say unmentionable things, forbidden words and ideas, fantasies. She might blow softly in my ear. She might lick or nip at my neck. She might, when no one was watching, step behind some semiprivate barrier—a hedge on one of the manicured lawns, a half wall in a restaurant, an open car door in a parking lot—and lift the gauzy lengths of her skirt, quickly and flirtatiously, to show me her smooth dark skin and the plain silken panties hiding her sex.

She was full of suggestions:

“If you return home for your lunch today, I will be happy for your visit.”

“Bashar is traveling to Nasiriyah for two days. I would like you to come help me move some furniture in our living room.”

“Perhaps you should give me a key to your house so that I can make sure you are safe at night.”

I don’t think such lewdness came naturally to her. I think it was partially a product of her experiences in Chicago, soap-opera ideas of infidelity and drama. I also think it was partially, and more importantly, a cover, a way to prevent us from discussing the really hurtful matter that lay between us.

She tried to broach this subject once, one such moment, saying, “What is it about her, this Annie, that I don’t have?”

I thought about it for a bit before answering her. It was nothing I could express well, but I tried my best.

“You’re normal,” I said.

She just frowned and went back to her previous method of attack, keeping me on edge, frustrated, painfully aware of her desire for me. Bashar surely suspected her. She was only partially discreet. But what could he do? Nothing, except to uproot his family once again and restart his life somewhere quiet, somewhere safe, somewhere more traditional. Somewhere like Safwan.