Operation Mercury (11 page)

Authors: John Sadler

This was not the only shortcoming of the defence of Maleme; the lighter AA guns, manned by marines, were controlled by Weston, the heavier AA weapons took their orders from the Gun Control Room in Chania. Though Andrew made representations to Puttick about the lack of deployment west of the Tavronitis nothing was done and the âback door' remained ajar. Moves were considered to move some of the Greeks at Kastelli further east but all that was finally done was to detail a single section from 21st Battalion to occupy a single vantage as, to all intents and purposes, observers.

Air Marshal Longmore, having inspected the Souda Bay area, concluded it could be kept clear of German bombers by a full squadron of Hurricanes, with 100 per cent replacement rate and reserve of pilots. This may have been optimistic but Freyberg hoped he would at least receive this complement of fighters. He was to be disappointed as the debate raged at the very highest level over how the supply of available planes and pilots was to be doled out. The RAF sought to shift the burden onto the Navy; Cunningham hedged in response.

The final proposal was the worst of bad compromises. The island, it was felt, could not be adequately defended from the air given the heavy demands made by operations in the Western Desert but, and this was crucial, the air strips with their attendant personnel were to be kept at operational readiness. The idea was that, should the Germans invade from the sea, aircraft could then be dispatched from Egypt and based at these forward strips. For this reason the runways were not lighted.

By mid May the few available aircraft, stationed on the island, had been steadily whittled down by attrition. By the 19th Beamish had convinced a reluctant Freyberg that the battered survivors should be withdrawn from what was becoming a hopeless fight. This must have been a bitter moment; the fearful scenario he had envisaged at the outset had become a reality, his forces were without air cover, exposed to the full fury of the Luftwaffe.

There was, however, on Crete one officer whose preferred defence against parachutists was his trusty sword stick. John Pendlebury, a field archaeologist and Old Wykehamist in his mid-thirties, was one of those brilliant mavericks, in the vein of T. E Lawrence or Orde Wingate. He'd been curator of Arthur Evans museum collection at Knossos in the previous decade and knew the island and its people intimately. Military Intelligence had recruited him as early as 1938 to serve in what would become the Special Operations Executive (SOE); at that point Military Intelligence (Research) MI(R).

First dispatched to Greece in the wake of the German onslaught on the Low Countries in 1940, his credentials overcame the Greeks' suspicion of British clandestine operations on their soil; at this point Metaxas wished to avoid provoking the Axis. Pendlebury soon made his way to Crete where he had deep knowledge of the landscapes, gleaned in the course of his many walking trips around the island. In addition to his sword-cane he also sported a glass eye which he took to leaving on his desk when engaged in the field!

His official role was that of Vice Consul in Heraklion but he was soon abroad, organising the Palikari â such was his charisma that he was soon able to report he had established the basis for an intelligence and, if needed, resistance network. As MI(R) began its complex transformation into SOE, Pendlebury was somehow overlooked and continued, unfettered by official constraint, on his own initiative. One of his concerns was the reluctance of the government to arm the Cretans, still fearful of their republican sympathies.

Two of his intelligence colleagues, Terence Bruce Mitford and Jack Hamson, were sent in as support with a particular brief for potential sabotage operations against the Italian invaders on the mainland. However, with the Axis advance halting under way, Pendlebury was appointed as official liaison with the Greek army.

Having neatly circumvented the territorial restrictions imposed by demarcations within the intelligence organisations, he was able to set up a school for saboteurs on Souda Island. Nonetheless the severe restrictions placed on the team's remit by Cairo meant that by the time Greece had fallen and an invasion of Crete appeared imminent, frustratingly little had been achieved.

The mainland debacle added a sudden jolt of real urgency and the SOE activity on Crete was geared up accordingly. It was now proposed to make the island a training ground and operational base for guerrilla activity throughout the Axis occupied Balkans. A new SOE HQ was established in a pleasant villa in Chania and Pendlebury's brief, to recruit local resistance groups, was given fresh impetus.

For a brief moment, the troops on Crete, despite the regular attentions of the Stukas, gained a respite. The island, largely untouched by the war, was lovely in the Mediterranean spring, the air heavy with the scent of thyme. Those early days in May were an opportunity to recover from the ordeal of Greece:

I had a most heavenly bathe this evening with David Barnett. As I told you this is the most beautiful place and we found a lovely little sandy cove, surrounded by rocks, about three miles away. The water was crystal clear and just cool enough to be refreshing, with a pale blue tint. We sat on the rocks and dried in the evening sun, which doesn't burn you here. It wasn't like war at all.

34

As expectation lay heavy in the scented island air and the troops, battered by their ordeal in Greece, recuperating in the glorious warmth of the Cretan spring, basked in the delicious shade of the olive groves or swam in the revitalising waters, General Freyberg spent his days touring the defences. The presence of this great, bluff bear of a man brought heart to many young soldiers. His very obvious concern for their welfare, his legendary valour and his curt injunction just to âfix bayonets and go at them as hard as you can' were reassuring.

Some of his officers were a deal less sanguine, however. Their general's preoccupation was with resisting a seaborne threat, his obsession with the business of âwiring in' â straight from 1918. This appeared to be the antithesis of rapid reaction and relentless counter-attacks which was the accepted response to parachutists.

Freyberg had, in his operational orders, placed reliance on the force reserves. These were considerable but their correct deployment remained dependant on a number of factors â sound communications, speed and cohesion of response. The plain fact was that the reserves were scattered along the ribbon of coast without sufficient transport and, above all, with poor communications.

Here lay the nub of the problem. Many wireless sets had been lost in Greece, those which had been salvaged were few in number and, at best, indifferent in quality. Amazingly, Freyberg had not included radios in his âurgent' list sent out on 7 May. Communications otherwise depended on field telephones, the wires strung precariously on poles along the length of the coast road.

Field telephones had proved totally inadequate in the previous war and were particularly vulnerable to casual interdiction by paratroops. Even the signal lamps had no batteries or were of the wrong voltage requirement for the fitful mains. This ad hoc and grossly inadequate system of communications was a major and telling weakness.

Due to strict adherence to Air Ministry requirements,the airstrips had not been mined or slighted and Freyberg's vision of a descent from the sea rather than the air continued to blind him to the threat, should the Germans prove able to snatch one of the aerodromes intact. On 16th he sent a final, pre-invasion signal to Wavell in Cairo, the tone upbeat and confident:

[I] have completed plan for the defence of Crete and have just returned from final tour of defences. I feel greatly encouraged by my visit. Everywhere all ranks are fit, and morale is high. All defences have been extended, and positions wired as much as possible. We have forty-five field guns placed, with adequate ammunition dumped. Two infantry tanks are at each aerodrome. Carriers and transport still being unloaded and delivered. 2nd Leicesters have arrived, and will make Heraklion stronger. I do not wish to be over-confident, but I feel that at least we will give excellent account of ourselves. With help of Royal Navy I trust Crete will be held.

35

This then was the state of the island's defences on 19 May; time had now run out. Churchill was right to point out that the loss of Crete was indeed sad. It was to be, even on the most lenient of assessments, an avoidable defeat. Inertia, lack of organisation, lack of a coherent strategy for the defence, and the under use of resources, were to contribute as much as the lack of air support to the tragedy.

Freyberg, a lion in battle, was not the man to lead this complex defensive action; his analytical failings, understandable as they were, contributed mightily. This poor strategy and lack of preparedness would combine to frustrate the desperate and inspiring heroism of the British, Australians, New Zealanders, Greeks and Cretans who fought so hard and so well during the course of the battle.

Fallen Flower Petals â Maleme, Chania and Rethymnon 20 May

The screaming Junkers over the grey-green trees,

Their cargoes feathering to earth.

They might be wisps of white rose petal

Caught in the keen, compelling twist of fate

Faltering, aimless, in an aimless wind:

Confetti, white and dirty white,

Tossed out in scattered handfuls â¦

And one man idle, leans against the open hatch,

Through which the white horde poured

And watches Crete whine past below,

And in the mixed array of conquest

His hearing does not catch the rifle snap,

Sudden, faint his hands grasp deeply into nothingness,

And in bewildered agony

The dark soul drowns.

Â

He struggles as the troop plane banks;

Unstruggling, falls in one slow turn -

The horror dream personified -

And the olives snatch him to their greenery.

Our vague ears do not catch the death â weak cry,

And someone blows the smoke shreds from his rifle mouth

.

1

It was shortly after 8.00 a.m. on the morning of 20 May. As ever in the eastern Mediterranean in the middle of spring, the weather was fine and clear with the promise of a very warm day.

Then from out to sea came a continuous, low roar. Above the horizon there appeared a long black line as of a flock of migrating birds. It was the first aerial invasion in history approaching. We looked spellbound.

2

At first the Allied soldiers had thought the initial rumble of aero engines was nothing more than their daily dose of strafing arriving, but it quickly became apparent that this was something altogether more serious. As Private Peter Butler of 22nd Battalion, recalls:

The morning of the 20th was fine and sunny and calm, there was no early morning strafing, we'd stood down, and while we were waiting for breakfast I was ordered to take the daily parade state to battalion headquarters on or near the top of the hill. I had on my web gear, no pack and carried a rifle. As I left the siren sounded but there was no sign of aircraft. About a quarter of an hour later the siren sounded again and I thought that was strange; there must be a big one coming. I couldn't remember being told this was the invasion alarm. By this time I was at headquarters, and bombing and strafing started and really worked into quite a noisy show. This, I guess, went on for about twenty minutes and then stopped. There was a strange silence. I came out of the slit trench and looked around. Apart from a few fires on the âdrome there was no visible damage. Shortly, a distant roar of engines could be heard approaching from the north and then from over the sea came the sight of countless planes from as far east to as far west as could be seen, from horizon to horizon. The roar became louder and louder until they were overhead.

3

Quite close, WO Les Young was at breakfast with the 21st:

Breakfast was served at the usual time, I think 0730 hours and immediately after breakfast the men in my battalion were engaged in sharing out papers and parcels which had arrived late the previous night and which were addressed to personnel who had remained on the mainland of Greece. While this was going on a roar was heard in the sky and over came ME109s, Dorniers and Stukas and commenced strafing and bombing the area all around. There was a terrific din and the sky was black with planes. Apart from an odd bren gun I did not hear any ack ack [anti aircraft] fire. They were followed very shortly by the lumbering JU52s and ghostly gliders.

4

Sweeping in at under 400 feet, beneath the elevation of the heavier AA guns, the Junkers kept in tight formation until they reached the drop zones, then the air blossomed with a blizzard of colour â pink or violet denoted an officer, O/R's black, weapons, white. This was a vast aerial armada, the like of which had never been seen before, a Wagnerian chorus of thundering engines and myriad planes, filling the vast blue of the eastern Mediterranean sky like giant, metal locusts, a plague; the judgement of God.

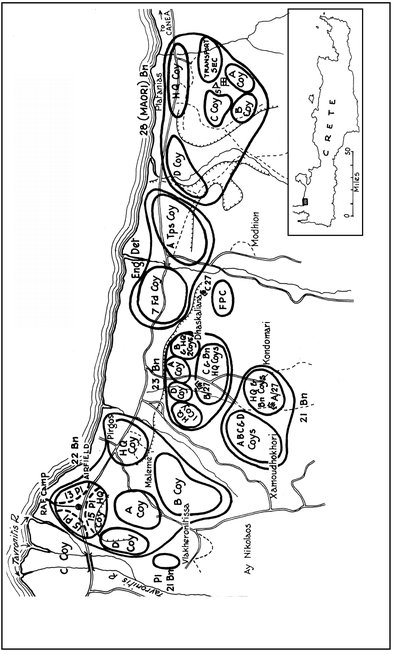

The dispositions of the New Zealan 5th Brigade about and on Maleme aerodrome immediately preceeding the attack on 20th May

[Freyburg] stood out on the hill with other members of my staff enthralled by the magnitude of the operation. While we were watching the bombers, we suddenly became aware of a greater throbbing in the moments of comparative quiet and looking out to sea with the glasses, I picked up hundreds of planes, tier upon tier, coming towards us. Here were the huge, slow moving troop carriers with the loads we were expecting. First we watched them circle clockwise over Maleme aerodrome and then, when they were only a few hundred feet above the ground, as if by magic, white specks mixed with other colours suddenly appeared beneath them as clouds of parachutes floated slowly down to earth.

5

This vast airborne fleet, sweeping in from the sea to deluge Crete, was the culmination of Student's dream, the final working of his theories on vertical envelopment. The General in Athens might be heartened by the sight of his creation springing to awesome life but he could not be unaware of the risks; failure would, at best, end his career.

If the 3.7-in guns couldn't register, the Bofors, manned by the marines, certainly could and they fired till the barrels glowed red. The slow moving transports were a gunner's dream and the shells tore through metal and flesh, dismembering men and aircraft in mid air, slain parachutists tumbling âlike potato sacks' from the wrecked fuselages.

Hanging from telegraph poles, caught in trees, dumped in ditches, the dead bodies of

Fallschirmjäger

, the corpses swelling, putrid in the heat, a new feature of the island landscape. Was this to be the face of vertical envelopment? Scarcely what its creator had envisaged.

One of the prime weaknesses of the German tactical approach to parachute operations was the poor design of the harness. The lines were fastened to a webbing harness that held the wearer suspended as he dropped. He had the ability to use the personal weapons he had with him, but could not influence the course of his descent. Once the chute opened he was at the mercy of man and the elements till he touched down. From the ground, Charles Upham saw clearly just how vulnerable the

Fallschirmjäger

could be:

The easiest sort of warfare in the world. If they landed where you were or within range of where you could get to they were just sitting ducks, they had no chance. Of course the whole object of parachute troops is to land them where there isn't anybody â out of sight. Once they get on the ground and regroup they've always got the very best of weapons and things like that. But while they're in the air â gliders and paratroopers in the air â oh, they're the easiest things in the world to bring down.

6

The bombing and strafing that preceded the attack was over but Stukas and Me109s still prowled the skies, ready to provide close air support and pounce on targets of opportunity. Unknown to Student a copy of the parachute training manual had been recovered from an earlier assault the previous year and the defending troops were thus versed in the principles of immediate counter-attack at every point of landing to prevent concentration. This was the moment of maximum danger for the parachutists, scattered, disorientated, separated from officers and weapons.

If the defenders were at first stunned and awed by the power and noise of the assault, they very soon recovered. Peter Butler continues:

There was perhaps a minute's awestruck inactivity while people realised what was going on, then firing started from all over the area. Some paratroopers were firing machine pistols as they came down but this stopped quite a way from the ground and it appeared the majority were hit while still in the air. The gliders around us fared little better. They came in so low one could not miss. I saw one man firing a bren from his shoulder literally tearing a glider to pieces â bits were flying off it. It landed about twenty yards from me and only one man came out. He only made about two steps before he was cut down.

7

This rapid response did not occur west of the Tavronitis where the western flank of Major General Eugen Meindl's assault on Maleme landed unopposed; Major E. Stenzler's 2nd, and Captain W. Gericke's 4th Battalion of the Luftlande Regiment, accompanied by two heavy weapons companies with anti-tank guns and mountain howitzers; with them Lieutenant P. Muerbe and a commanded party of a reinforced platoon whose job was to secure the extreme western end of the island by taking Kastelli and the half finished airfield there.

Major O. Scherber with 3rd Battalion, divided into company sized groups and dropping along the line of the road between Pirgos and Platanias, comprised the eastern flank whilst the centre was left to glider-borne detachments under Majors Braun and Koch. The sedate, huge winged aircraft, swooping silently like prehistoric creatures, had spilled around the banks of the Tavronitis, ready to disgorge troops and their heavy equipment and guns. Their task was twofold; Braun was to silence the Bofors guns at the dry mouth of the river and secure the bridge; Koch to assault Hill 107.

As the lumbering transports began to appear over Maleme airfield, Major Rheinhard Wenning, in charge of the actual dispatch of the airborne troops:

⦠suddenly with a terrible sound my plane lurched forward and I could just see out of the corner of my eye that the right wing of the plane on my left was touching our wing. It could have been serious because obviously that pilot was concentrating on what was happening on the ground and didn't realise his plane had drifted into mine. We averted disaster by lowering our flap and banking to the right.

Then:

As we brought the planes down to the required height of 150 metres above ground, and slowed to 160 km per hour we could see in front of us the first parachutes swelling out, then, in rapid order, more and more ⦠then Captain Wenndorf gave the signal for the jump by our unit by pointing a yellow flag through the roof of the cabin. Seconds later repeated shocks shook the plane, a sign that our parachutists were jumping out ⦠I looked down at the ground and saw one parachutist after another landing down there in an area which I can only describe as very difficult; mountain formations, very rugged and chalky, vineyards, olive groves, and dry fields, with small villages and narrow roads. Everywhere in this landscape were the countless white spots of parachutes, in trees or on the ground, where the soldiers had discarded them. And I could see parachutists moving into position and the first fighting erupting.

8

Both Bofors and Brens should have taken a fearful toll, but it was mostly these lighter weapons that did the killing, shredding the fragile gliders. A deal of dispute hangs over the question of why the heavier guns at Maleme proved ineffective. There is consensus that the heavier AA guns did not fire at all. It may have been, as has been asserted, that the weapons were lacking parts, though other witnesses record test firing for several days prior to the invasion being successfully carried out.

A number of defects seem to have played a role: the guns were badly sited which made them relatively easy targets for the Me109s. The batteries were poorly camouflaged which added to their vulnerability and the arc of fire expected was too wide; better positioning of the individual pieces would have permitted a better concentration of fire.

These shortcomings were particularly acute at Maleme where the AA guns were deployed to cover the airfield itself:

Since the effective range of the Bofors is little more than 800 yards, the gun positions were of necessity near the fringe of the aerodrome, and, in consequence most conspicuous and vulnerable. As soon as we were no longer able to operate from the aerodrome the role of these guns had changed. Their primary task should then have been to deal with troop carriers trying to land. They would have fulfilled their task much more effectively if they had been disposed irregularly at a distance from the aerodrome.

9

Above the strip heavier guns were dug into the hillside. Their job was to act, not only in an anti-aircraft role, but also to cover the beaches â again the pre-occupation with a landing from the sea dominated defensive strategy. In the event these pieces proved useless as the barrels could not be depressed sufficiently to fire on the German transports, ideal targets as these were. The troop carriers came in, sticking to their low altitude, from the south, swinging in over the land to turn before the drop. No gunner can have had a finer target.

Any number of reasons, many of them sound, can be advanced as to why the available guns, which should have been more than adequate, were so badly sited: lack of transport, the difficulties moving the weapons under constant bombardment, but the primary reason was that the defensive planning was firmly fixated on an attack from the sea. To that extent Student's plan for vertical envelopment had worked. The concept was so breathtakingly audacious, it had clearly reflected its creator's genius for innovation.