Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (37 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

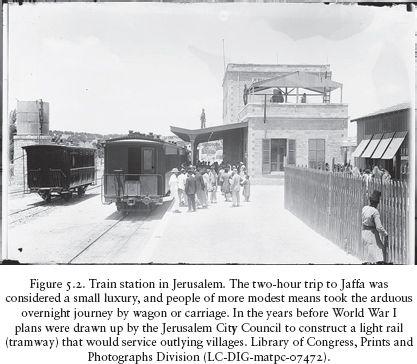

However, only months after Mavrommatis was granted the Jerusalem concession, the First World War broke out, and all plans for development in Jerusalem were shelved. It would be the British, not the Ottomans, who would be seen as “bringing modernity” to Jerusalem, in the form of running water, electricity, and telephone lines. And yet, the story of the SCP and its efforts to promote local development is inseparable from its politically Ottomanist mandate of uniting the Muslims, Jews, and Christians of Jerusalem as a force for local progress and development.

This shared civic commitment was evidenced in the proposed tramway lines for Jerusalem, as the six proposed lines took into account the interests of the Muslim, Jewish, and Christian resident communities as well as the needs of the city's many pilgrims and tourists. The tramway would have linked the Old City and the New City, secular spaces (the Schneller School, the municipal hospital) and spiritual spaces (Mount of Olives, Saint Croix), commercial markets and residential neighborhoods. The tramway also would have linked Jerusalem with some of its neighboring villages, Christian Bethlehem to the south and Muslim Shaykh Badr to the west.

61

A similar apolitical civic spirit emerged in the proposed tramway lines for Jaffa that also targeted areas of importance to the city's Muslim, Christian, and Jewish communities. The hub of the tramway was to be the government house and the two lines were to pass through major neighborhoods (‘Ajami, Manshiyya), stop at important religious sites (the tomb of Shaykh Ibrahim al-‘Ajami), hit important commercial centers (markets, the import office, the German bank, the tobacco concession office), pass by two public fountains, and link the city with neighboring villages (Muslim Yazur and the new “Hebrew” suburb of Tel Aviv).

62

The partnership between Jerusalem's business and civic leaders to promote the city's modern development could not have occurred against a blank slate, and in fact, it built upon a good deal of economic and commercial partnerships that existed between Muslims, Christians, and Jews in this period. For example, in the autobiography of Yosef Eliyahu Chelouche, a young Jew of North African provenance in Jaffa who was a prominent builder and merchant at the time, we learn that he partnered with Jurji ‘Abdelnour, a Christian, and Khalil Damiati, a Muslim, to import wood from Rhodes; he also named numerous other individuals with whom he and his relatives were engaged in business, political, and personal exchanges.

63

Rather than looking at these economic relationships (business partnerships, loans, sales and rentals, etc.) as transactions limited in time and space, I instead view these economic ties as important evidence of strong, ongoing social networks. Indeed, Chelouche's memoir is a testimony to the extensive network of relations that he, his father, uncle, and brother maintained with their Muslim and Christian neighbors. More poignant, Chelouche gratefully and painstakingly recounted each individual who aided him and his family during World War I, highlighting their place in his extended social network, whether it was a former business partner who lent them money, grain, and camels or a former employee who became a military prison guard and in turn aided his one-time patron. These relationships were based on trust, respect, and the common belief in a social system that rewarded both. For example, Chelouche mentions that his uncle Avraham Haim Chelouche famously conducted business with Bedouin tribal nomads from Bi'r al-Saba‘ (today's Be'er Sheva') and Muslims from Gaza without counting his receipts, trusting them to tell him the correct amount they owed and paid.

In most cases, these relationships took place in informal setting—the

diwan

(sitting room), the market, the neighborhood. By the turn of the twentieth century, however, new social institutions such as Freemason lodges had emerged as an institutionalized setting for social interaction and the creation of new social ties of solidarity.

BROTHER BUILDERS

From the mid-nineteenth century, Freemasonry provided a fertile philosophical and organizational ground for Ottoman liberal thinkers and reformers. Incorporating a belief in a Supreme Being, secretive rituals, and modern Enlightenment ideals, Freemasonry offered its members a progressive philosophical and social outlook, an important economic and social network, ties to the West, and a potential arm for political organizing. According to one historian of Ottoman Masonry, “By the end of the [nineteenth] century, there was hardly a city or town of importance without at least one lodge.”

64

While the British model of Freemasonry was more conservative in bent and generally was supportive of the religious and political status quo, the French tradition of Freemasonry which became more prominent throughout the Middle East emphasized liberal, philosophical positions and encouraged political engagement and critique, including support for revolution. In Egypt Freemasonry provided an outlet for political and social organization in the aftermath of British colonization, and Masons played a prominent role in the 1882 ‘Urabi revolution.

65

Indeed, the prominent Islamic anticolonial activist Jamal al-Din al-Afghani consciously linked a desired political reform with his Masonic activities: “The first thing that enticed me to work in the building of the free was a solemn, impressive slogan: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity—whose objective seemed to be the good of mankind, the demolition of the edifices and the erection of the monuments of absolute justice. Hence I took Freemasonry to mean a drive for work, self-respect and disdain for life in the cause of fighting injustice.”

66

We recall, of course, that al-Afghani had numerous protégés and disciples throughout the Ottoman world, especially in Istanbul and Cairo, and as a result, Freemasonry emerged to be one of the most important organizations during the Hamidian period. A number of leading Young Turks were active Masons before 1908, possibly because of the immunity from police scrutiny that the foreign lodges offered.

67

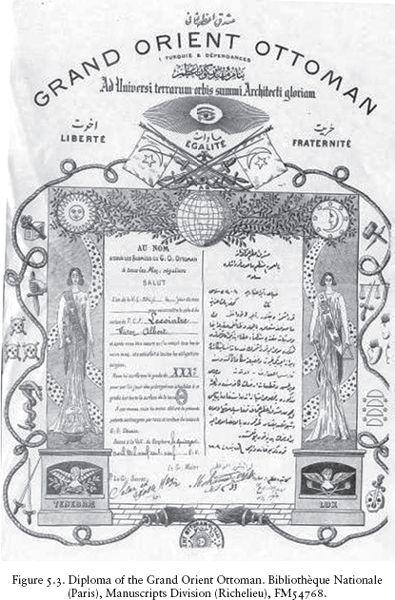

After 1908, far from its origins as a closeted secret society pursued by the state and its secret police, Freemasonry was legitimized and institutionalized as part of the new sociopolitical order. In 1909, the long-defunct “Supreme Council” of the Scottish rite of Masonry within the Ottoman Empire was reconstituted under the leadership of Minister of Finance Cavit Bey, MP Emmanuel Carasso, MP Dr. Riza Tevfiq, and other luminaries of the CUP. Also that year, the Grand Orient Ottoman (GOO; sometimes called the Grand Orient de la Turquie) was established as

the umbrella mother lodge of the empire, and Ottoman Minister of the Interior Talat Pasha was elected grand master. In establishing the GOO, the leadership sought to establish an autonomous Masonry in the spirit of political and national emancipation as well as to form a core of constitutional liberals who would be able to stand up to the reactionaries still found throughout the empire.

68

With this kind of institutional support, it is no wonder that Freemasonry flourished openly in the empire in the revolutionary era. Between 1909 and 1910, at least seven new lodges were established or old ones revived from dormancy in Istanbul alone; most of them had names that linked them to the new spirit of liberty and progress: Les vrais amis de l'Union et Progrès, La Veritas, La Patrie, La Renaissance, Shefak (L'Aurore). In Salonica, Masonic lodges multiplied so much that another historian has characterized it as “proliferation that was likely to emerge, shortly, in a true Masonic colonization of the Ottoman Empire.”

69

In Jaffa, the existing lodge, Barkai, exploded numerically, and in the following years several new lodges were established in Jaffa and Jerusalem.

70

As a stark illustration of the rapid growth of Freemasonry in Palestine, in contrast to the 57 known Palestinian Masons who were active in the seventeen years before the July 1908 revolution, in the seven years after it, another 131 young men were initiated as Masons. Surely at least some of the men newly drawn to Freemasonry joined out of philosophical affinity. One surviving application for admission to a Beirut Masonic lodge describes the aspirant's motivation precisely in this way: “The Freemasonry order is an order that has rendered great services to humanity throughout the centuries and always raised high the banner of equality, fraternity, and liberty. It is an order that seeks to bring together mankind and to better it. I would also like to be part of such an order, to take part in benevolence and the useful works of your order.”

71

In the catechism for the first degree, the apprentice initiate was asked to reiterate the philosophical aims of Freemasonry in numerous ways:

QUESTION:

What is a Freemason?

RESPONSE:

He is a free man of good qualities, who prefers above all justice and truth, and who banishes prejudice and vulgarity, is equally friend of rich and poor, if they are virtuous.

QUESTION:

What is Freemasonry?

RESPONSE:

Freemasonry is an institution whose aim is to establish justice in humanity and for brotherhood to reign.

QUESTION:

Why do you desire to be a Freemason?

RESPONSE:

Because I am in darkness and I desire enlightenment.

QUESTION:

What does a lodge do?

RESPONSE:

It combats tyranny, ignorance, prejudice, and errors; it glorifies law, justice, truth, and reason.

72

New members swore to abide by these principles as well as to promote mutual aid, public service, and Masonic loyalty, on pain of excommunication.

At the same time, it is also likely that at least some of the new Masons joined out of more worldly considerations, taking into account the close relationship between the Young Turks and the Masonic movement which gave it a crucial stamp of approval as well as a certain cachet. Indeed, several longstanding Masons expressed unease at the rapid proliferation of the movement in the revolutionary era. At least one Salonican lodge affiliated with the Grand Orient de France (GODF) objected to the establishment of the GOO on Masonic grounds, complaining to Paris, “among the reasons which push to me to place obstacles at the development of this new Masonic power is that I noted, alas, that the lodges subjected to its influence completely neglect the regulations of the Masonic statutes and regulations with regard to the recruitment of the members and blindly are subjects to the instructions of parties which work with another collective aim.” Within weeks, however, Mason de Botton's reservations had dissipated, and he wrote to the GODF to ask them to do all that was “humanly and Masonically possible” to recognize the GOO.

73

Nonetheless unease continued, and another Mason complained later that “each [new initiate] wanted to become a Mason like the leaders of the new order. Those who entered a lodge by conviction were not very numerous.”

74

While we cannot know the motivation of each new (or, for that matter, old) Mason for certain, we do see a pattern of less intensive Masonic involvement on the part of these new initiates. A large percentage of the post-1908 initiates remained at the lowest Masonic level, that of apprentice, suggesting either insufficient Masonic fervor or insufficient preparation for promotion.

However, whether their motivations were ideological, political, personal, or a combination of all three, it is clear that new members were entering into one of the rare sites of institutionalized interconfessional, interethnic, and international sociability available in the Ottoman Empire.

75

The historian Paul Dumont gives as an early example the 1869 membership count of the Salonican lodge L'Union d'Orient: 143 brothers, among them 53 Muslims. As well, the “Prométhée” lodge in Janina was a mixed Greek-Muslim-Armenian-Jewish lodge until the 1897 Greco-Turkish war closed its doors.

76

In Palestine, of the 157 known

members and affiliates of the main Masonic lodge from 1906 to 1915, 45 percent were Muslim, 33 percent were Christian, and 22 percent were Jews.