Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (38 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

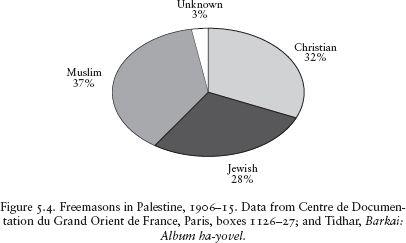

This is startling, considering that much of the anti-Masonic literature in the Middle East, historically as well as at present, denounces Masonry as the purview of the “minority” Jewish and Christian and foreigner European communities. The high participation of Muslims from Palestine and other parts of the Ottoman Empire in Masonic activity contradicts this charge, although it is still true that there was quite a significant overrepresentation of Jews and Christians in the lodges—roughly double their presence in the wider population.

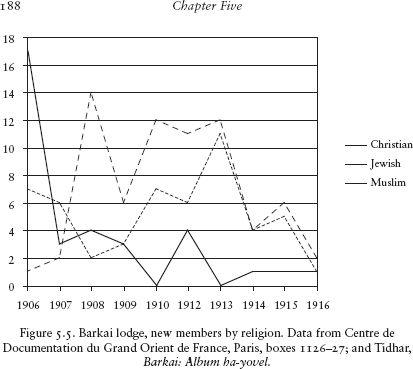

The membership records of Barkai lodge in Jaffa also show quite starkly that the appeal of Freemasonry to Palestine's Muslims rose concurrent with the 1908 revolution. Originally founded in 1891 by Jews and Christians as Le port du Temple de Salomon and reconstituted in 1906 under French tutelage, Barkai emerged as the most important Masonic lodge in southern Palestine, a center for leading members of the political, intellectual, and economic elite of the province. At the beginning of 1908, Barkai had only three Muslim members out of thirty-seven total members; by the end of 1908, another fourteen Muslims had joined the lodge along with six Jews and Christians, marking the first time that new Muslim enlistment in the lodge exceeded that of the other two communities. In the six years following, new Muslim recruits exceeded both Christian and Jewish recruits every year; in most years the Muslim initiates exceeded new Jewish and Christian members combined.

Beyond serving as a “neutral” meeting ground for members of different religions, Masonic lodges also served as vehicles for internal solidarity and social cohesion across various middle-strata and elite groups.

77

By and large, the lodges did not attract the older, established leaders of each community, but rather the “new generation” on the rise. Most Palestinian Freemasons in this period joined in their mid-twenties to mid-thirties (the average age was 31.8 years old at time of pledging), although they were sometimes younger (especially with family legacies) and sometimes older. These were the same men who supported the CUP, and later, the various decentralization and nationalist parties.

The members of Palestine's Masonic lodges were largely of the newly mobile middle classes of the liberal professions as well as younger members of the traditional notable families.

78

Fully one-fourth were government employees: fifteen lawyers and judges, seventeen administrative officials at both the provincial and municipal levels, and a dozen members of the military and police. Another third worked in commerce, banking, and accounting. The rest of the members were teachers, doctors, pharmacists, lawyers, and white-collar clerks.

Notable Muslim Masons included members of the ‘Arafat, Abu Ghazaleh, Abu Khadra', al-Bitar, al-Dajani, al-Khalidi, al-Nashashibi, and al-Nusseibi families, most of whom fulfilled important state functions.

79

The Christian Masons were members of the growing middle classes, primarily employed in commerce and the liberal professions, from the Burdqush, al-‘Issa, Khoury, Mantura, Sleim, Soulban, and Tamari families. Among the Jewish members, the Ashkenazim were largely colonists who had arrived in the 1880s and 1890s to live on the early Zionist agricultural settlements, adopting Ottoman citizenship upon arrival. The Sephardi and Maghrebi Jews, on the other hand, were younger members of economically and communally established families: Amzalek, Elyashar, Mani, Moyal, Panijel, Taranto, and Valero.

80

Thus there was a certain degree of what one scholar has called the “democratic sociability” of the Freemasonry movement.

81

The radical innovation of a single organization that would voluntarily encompass—and equalize—Khalidis and Nashashibis as well as Burdqushes, Manis, and other young men from less illustrious families cannot be overlooked. At the same time, however, Freemasonry had the effect of reaffirming class lines. These men shared similar modes of modern education, exposure to foreign languages and Western ideas, a relatively high level of economic independence, and a growing sociopolitical weight in their province and the empire as a whole.

82

To a certain extent, this group was preselected and self-perpetuating. In order to be accepted into a lodge, a prospective candidate had to secure the sponsorship of two lodge members in good standing. These recommendations often came from relatives (older brothers, cousins, uncles, sometimes fathers); in fact fully 32 percent of all Freemasons in Palestine had family members who were also member Masons, highest among Christians and Muslims.

83

As well, educational and professional ties also proved significant. Among the members of Barkai lodge were at least six recent graduates of the American University in Beirut in addition to many who had studied in the various professional schools in Istanbul.

84

Nine employees of the Jaffa and Jerusalem branches of the Ottoman Imperial Bank were brother Masons. Notably, only one Palestinian Mason was born in a village, and only one Mason was a religious functionary (in the Greek Orthodox Church). In this sense, then, Masonic lodges served as social networks for the growing middle class and governmental urban elites.

Because of this demographic and professional profile, networking played a huge role in Masonic appeal and cachet.

85

Inter-Masonic commercial relationships were frequent, and it was not uncommon for businessmen to request letters of introduction with a Masonic stamp of approval. Such a letter was obtained by Yosef Eliyahu Chelouche,

who was not himself a Mason, from then-Venerable of the Barkai lodge Iskandar Fiuni (Alexander Fiani) in preparation for a business meeting with a Greek contact in Egypt.

86

Furthermore, a significant number (22 percent) of Freemasons in Palestine belonged to other Masonic lodges, whether locally or abroad, indicating the extent to which Freemasonry itself served as an overlapping affiliation network.

Masonic Activities

In the winter of 1913, a shocking case of “Masonic treason” rocked Palestinian Freemasonry: an Italian doctor named Salvatore Garcea had penetrated the Moriah Masonic lodge in Jerusalem and reported its activities both to the anti-Masonic French consul and to the heads of various religious communities. As a result of the exposé, seven or eight members faced “complete ruin.”

87

This context of religious persecution of Masons as well as the loss of the Barkai lodge archives during World War I make it difficult to retrace the full scope of Masonic activities in the late Ottoman world.

88

Nonetheless we do know that the Palestinian lodges' regular activities focused on philanthropy, mutual aid, and lay education. Lodge banquets were held to raise funds for the Ottoman army's winter clothing drive, for example. Lodge leaders regularly intervened on behalf of members, such as helping Anis Jaber, who was rendered destitute in September 1908. The lodge also lobbied on behalf of members with the Paris GODF headquarters, urging their assistance in one member's bid to be hired as director of the Rothschild Hospital in Jerusalem. In two cases of wrongful dismissal of Masons from the Jaffa-Jerusalem Railroad and the Messageries Maritimes at the Jaffa port, however, the GODF in Paris refused to intervene on the pretext that the economic importance of Jaffa to France overruled brotherly obligations.

89

Beyond that, we can only wonder at what sort of Masonic activity was implied when members spoke of their missionary-like activities of “contributing to the diffusion of Masonic ideas in this Ottoman Empire which is our fatherland, which greatly needs to take as a starting point our motto to ensure the well-being of its children.” In this context, Barkai requested that it be allowed to affiliate itself with the Grand Orient Ottoman in order to coordinate Masonic activities empire-wide.

90

Barkai's appeal for permission to affiliate itself with the new GOO, however, was not made simply out of Masonic brotherhood; rather, it also was seeking protection and alliance with the potentially powerful umbrella organization. Because of its close ties with leading members of the new government and ruling party, the GOO was an important friend

to have and to turn to, a fact not lost on Palestine's Masons who were under attack by a newly elected parliamentarian, apparently an avowed enemy of Freemasonry.

91

Eventually, in 1910, the GODF did establish “fraternal relations” with the GOO and authorized its members to fraternize with the Ottoman organization.

92

As a result, in June 1910, several members of Barkai lodge decided to revive the defunct Temple of Solomon lodge in Jerusalem under the aegis of the GOO; eventually, twenty-two members of Barkai joined the new GOO lodge. Within a couple of years, however, the Temple of Solomon would undergo an internal split that divided Palestinian Freemasonry along political and sectarian lines.

Brother Against Brother

Virtually nothing is known of the Temple of Solomon lodge until March 1913, when a faction of the lodge broke off and formed its own provisional lodge demanding “symbolic and constitutional acceptance” by the GODF.

93

The new lodge, named Moriah, immediately requested catechism books, proposed a lodge seal, began searching for a garden as lodge headquarters, and set strict guidelines for admission to the lodge: only those with “irreproachable reputations” and decent French need apply.

According to its new Venerable, the task of the Masons of Moriah would be to defend the ideas of freedom and justice, particularly in Jerusalem, where clericalism and fanaticism were strongly against Masonic work. Avraham Abushadid, newly elected speaker of the lodge, urged his fellow Masons to ensure that “mutual tolerance, respect of others and yourself, and absolute freedom of conscience are not words in vain.”

94

According to Abushadid, in the East “the word ‘freedom' is replaced by ‘servility' and ‘fanaticism,' while ‘equality' and ‘fraternity' are vocabulary replaced by the synonyms of superstition and hypocrisy.”

Through their Masonic mission, Abushadid envisioned a renaissance of the Ottoman people: “This new star which comes from our East, continues to shine with an increasingly sharp glare, and our path is clear…. The day will come when its luminous clarity will disperse all darkness, and the base of this shaking humanity will collapse and one will see then, all the nations, all the races, all the religions will be erased and disappear, and to make place for a rising generation, young people, free, fraternizing and sacrificing a whole glorious past, for a new era of peace, truth and justice.”

95

However, despite this claim of “erasing lines” between peoples, the split within the Temple of Solomon lodge had been a cultural and political one between two separate factions—one Arabic speaking, largely

Muslim and Christian; and the other French-speaking, largely Jewish and foreign. Of the eight known Temple of Solomon members who defected to form Moriah, five of them were Jewish, one Christian, and two were foreign Frenchmen. If before the split Temple of Solomon had been a relatively mixed lodge, with 40 percent Muslim, 33 percent Jewish, and 18.5 percent Christian members, postsplit Moriah had only one Muslim member. The “natives” of Temple of Solomon accused the “foreigners” of being, among other things, Zionists, while they were accused in turn of being “xenophobes.”

96

In the face of this growing schism between Freemasons in Jerusalem, the Temple of Solomon requested that the Jaffa-based lodge, Barkai, appeal to the GODF to deny Moriah's request for recognition.

97

According to Barkai Venerable Cesar ‘Araktinji, the presence of two competing Masonic lodges in Jerusalem would cause discord. His request was politely denied by the GODF, which had long wanted a lodge in Jerusalem. “Tell our Freemason brothers of the lodge of the Temple of Solomon that they should not look at [Moriah] as a rival lodge, but rather a new hearth working also to realize our ideals of justice and brotherhood.”

98