Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (20 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

African fishers

These ‘modern’ innovations were all things people made. When we look at what they did, we find an even more fascinating horizon of behaviour apparently starting between 110,000 and 140,000 years ago – just after the period of our emergence in the fossil record as a modern African species. While we should still not fall into the trap of automatically attributing new skills to any unique genetic change, it is worth looking at new behaviours that might have given us the edge over our large-brained ancestor,

Homo helmei

. Adapting to new and varied foods such as fish and shellfish may have been the key 150,000 years ago. Not to be outdone, Neanderthals also practised beachcombing 60,000 years ago on the Mediterranean.

32

Arguably the most important animal behaviour is obtaining food. The last 2 million years have seen more and more of Africa turn into desert, making it increasingly difficult to find food. Humans had to become more ingenious in order to stay alive, and moulded themselves into the highly evolved savannah hunter-gatherers that we became. Archaic humans were capable of hunting large and dangerous herbivores from the early Middle Stone Age.

33

A severe glacial period lasting from 130,000 to 170,000 years ago nearly wiped out the game on which human populations depended for calories and protein. It may therefore be no coincidence that from 140,000 years ago the African Middle Stone Age shows a new subsistence type – beachcombing – gathering shellfish on the seashore to supplement game as a source of protein.

Beachcombing was also seen in South Africa, at Klasies River mouth, but it is the Eritrean Red Sea coastal beachcombing site of Abdur that is most interesting for our story. This is, after all, where the Australian beachcombing trek may have started (see

Chapter 1

). Here, around 125,000 years ago, at the sea-level highpoint of the last interglacial we see Middle Stone Age tools and shellfish remains jumbled together with the butchered remains of

large African game (see

Plate 8

). McBrearty and Brookes argue that extension from beachcombing to actual fishing had occurred in Africa by 110,000 years ago.

34

I recently had the privilege of being shown the famous Abdur reef by its discoverer, Eritrean geologist Seife Berhe. Driving down steep escarpments, we left the cool watered highlands surrounding the capital, Asmara, 2,200 metres (7,200 feet) above sea level, and soon came to the baking coast of the Red Sea at the war-scarred, Arabflavoured port of Massawa. Stopping briefly for water and ice, we travelled south for three hours along a ribbed, dusty, all-weather coastal road. Stunning young volcanic scenery and high folds of mountains alternated with dry, silted alluvial plains. We were held up only briefly, by a puncture caused by a sharp volcanic rock.

This was the end of the dry season, and stunted bushes, mainly acacia, were the only green. The occasional gazelle, jackal, hare, bustard, or eagle were the only remnants I saw of the larger game that abounded here before the recent war. Everywhere we saw herds of camels, goats, cattle, and fat-tailed desert sheep. Apart from some nomadic herdsmen, the Afars are the only indigenous population on this part of the coast, and they stretch right down to Djibouti. Living in simple airy brushwood huts, the Afars were mutually dependent on their herds, and drew water for the entire flock every day from wells dug in dry river beds. We camped on the edge of one of these dry estuaries on a flat sandy plain, raised 10 metres (about 30 feet) above the beach.

I soon discovered that we were in fact camped on the famous raised 125,000-year-old reef. When the climate had started to worsen 120,000 years ago, the sea level had dropped, leaving this reef dry with all the different types of coral and shells beautifully preserved right up to the surface of the ground under our feet. A steady tectonic uplift had continued to raise the entire coastal reef another 5 meters (15 feet), creating a cliff that runs along the coast

for 10 km (6 miles). This extra uplift had protected the reef from the erosional effects of another high sea level 5,500 years ago.

The day after our arrival, we went down the cliff to the dry estuarine plain and found some friendly Afars watering their herds. To preserve the natural well, they drew up water in buckets and deposited it in large, dish-like mud basins they had built into the sand. While the cattle, goats, and sheep waited in single file for their turn to drink from these improvised troughs, the herders chanted a water-song.

Immediately above this ancient scene, Seife Berhe showed me the 125,000-year-old shell middens, the remains of meals of oysters looking as if they had been left behind only yesterday. Clearly visible, sticking out from but cemented in among the fossilized shells of the midden was an obsidian flake tool. From its shape it had clearly been worked, but it must have been brought to the reef because the nearest source of obsidian is 20 km (12 miles) away. The shell midden, butchered animal bones, the flake, and other obsidian artefacts completed the picture of a mixed diet eaten by the humans who lived by this reef so long ago.

Pieces of coral block were in the process of breaking away from the cliff, otherwise we would not have been able to climb and squeeze in so close. In the coral debris in the sand around these great blocks of coral were numerous small obsidian bladelets, 10–40 mm (0.4–1.6 inches) long, some very bright and sharp. I could have shaved myself with them. I remembered that the

Nature

paper reporting this important archaeological site had told of obsidian blades in the reef, but these were microliths. The puzzle was that 125,000 years ago should have been much too early for such small tools, unless they had been put there much later. The fact that they were loose, showing no clear association with the midden, made this an alternative possibility. Microliths start appearing in the African archaeological record only from 80,000 years ago. They were

present all over the sand above the cliff, so maybe that was the case. Interestingly, the earliest microliths outside Africa have all been found to the east of the Red Sea in Sri Lanka.

35

Last among the key elements of the ‘modern human’ behaviour package we find long-distance exchange – in other words, some form of trading or movement of important objects such as tools and raw obsidian over distances up to 300 km (200 miles). Again, we see in the African record that this most human of behaviours started at least 140,000 years ago.

36

Two million years of human know-how

McBrearty and Brooks’ composite picture of the first ‘Anatomically Modern’ Africans shows that soon after their first appearance, by around 140,000 years ago, half of the fourteen important clues to cognitive skills and behaviour which underpinned those that eventually took us to the Moon were already present. Three of these (pigment processing, grindstones, and blades) had been invented by the previous species of modern humans 140,000 years before that. By 100,000 years ago – just after the first exodus to the Levant – three-quarters of these skills had been invented; and the remaining three were in place before the first moderns stepped into Europe (see

Figure 2.5

). With such a perspective of cumulative increments in culture over the past 300,000 years, the concept of a sudden modern ‘European Human Revolution’ 40,000 years ago pops like a bubble. We begin to see instead our essential humanness as ‘adaptation and invention followed by physical evolution’ stretching right back into the 2-million-year story of our genus

Homo

– hunters, inventors, and tool-makers from the start.

In spite of this deconstruction of its evolutionary importance, the European Upper Palaeolithic remains a unique record of a most glorious period of local self-discovery. But what does it tell us about ourselves? Well, there are some hints, from the distribution and

dates of the earliest Upper Palaeolithic stone cultures that were clearly associated with modern humans’ invasion of Europe – the Aurignacian and its successor, the Gravettian – that there was not one invasion, but two. In the next chapter we shall find out why, where from, and how the genetic trail reinforces this view.

T

WO KINDS OF

E

UROPEAN

A

S WE HAVE SEEN

, the teasing issue of European origins is not just a matter of whether the future Europeans migrated out of Africa separately from the future Asians and Australians, or of just burying the myth that they were the first humans to show modern behaviour. It is more than that. Where did their extraordinary flowering of culture originate? Was it entirely home-grown, or was it imported? Why do some archaeologists argue for several different early cultural inputs to Europe in the period between 20,000 and 50,000 years ago – even one from the East? In this chapter we shall see that there are precise male and female genetic markers which parallel two different cultural waves that flowed in succession over the European archaeological record of the 25,000 years leading up the Last Glacial Maximum. These reveal that an ‘Eastern’ origin was no wild guess.

In

Chapter 1

we saw that the ancestors of Europeans, the N (or Nasreen) clan, belonged to one of the first branches off the single exodus shoot which arrived in southern Arabia perhaps 80,000 years ago. In spite of this secure position at the root of the Asian maternal genetic tree, the Europeans’ ancestors had to wait tens of thousands of years in South Asia. They waited until after 50,000

years ago, when a moist, warm phase greened the Arabian Desert sufficiently to open the Fertile Crescent and allowed them to migrate north-westwards towards Turkey and the Levant. Such constraints had not affected their cousins – the vanguard of beachcombers who pressed on round the Indian Ocean coast to Southeast Asia and Australia. They arrived in Australia over 60,000 years ago, long before Europe was colonized.

From an Asian point of view, Europe is an inaccessible peninsula jutting out north-west from the Old World, a geographical cul-de-sac. Genetically as well as geographically, Europeans are, similarly, a side-branch of the out-of-Africa human tree. Because the first non-African modern humans were Asians, ‘peninsular Europe’ was more likely to have been a recipient and beneficiary of the seeds of the earliest Upper Palaeolithic cultural innovations rather than their homeland. From this perspective the last chapter was devoted to deconstructing the archaeological/anthropological myth of a major human biological revolution defined in Europe and the Levant, with everyone else in the world following the European lead.

The first modern Europeans

We saw in the last chapter that our cousins the Neanderthals had already started to learn the smart new Upper Palaeolithic technology before their demise around 28,000 years ago. This partial blurring of the cultural distinction between Neanderthals and modern humans does not mean that archaeologists

cannot

detect the very clear cultural trails that mark the movement of the earliest modern humans into Europe. On the contrary, starting before 30,000 years ago, several such cultural traditions, specifically associated with modern humans, spread rapidly and successively across Europe. The dates and directions of spread of these traditions were different, and they have been given a number of names, based on the styles of tools and where the tools were found. The nature of the early modern cultures in Europe was diverse, and some archaeologists classify

them more broadly into two waves. The concept of movement can be taken even further than cultural diffusion to suggest two different human migrations with their associated cultures. The first of these waves, which commenced as early as 46,000 years ago, is called the Aurignacian, after the village of Aurignac (Haute-Garonne) in southern France, where typical artefacts were initially found. The later one, mainly from 21,000–30,000 years ago, is called the Gravettian after the French site of La Gravette in the Perigord region, and is characterized by backed blades (where one edge is blunted, like a penknife) and pointed blades.

1

It is tempting to attribute the spreading of ideas to mass migrations of people. However, as more recent history shows us, the movement of ideas and skills through populations can be more rapid and comprehensive than the movement of the people themselves. But for the first modern human colonizations of Europe there really does seem to be genetic evidence for at least two separate migrations corresponding to the new cultural traditions brought in by the moderns.

The Aurignacians

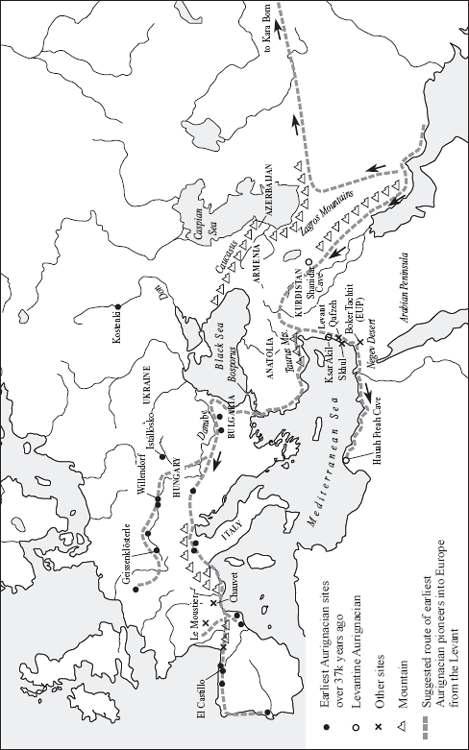

The Aurignacian Upper Palaeolithic culture first appeared in Europe in Bulgaria, presumably arriving from Turkey, after 50,000 years ago. Fairly soon after this, the new style of stone tools moved up the Danube to Istállósko in Hungary and then across, still westward along the Danube, to Willendorf, in Austria. The apparently relentless movement of Aurignacian culture, upriver and west from the Black Sea, eventually brought it to the upper reaches of the Danube at Geissenklösterle, Germany. Long before this time, however, the Aurignacian culture had also moved south from Austria into northern Italy. From there it spread rapidly, westward along the Riviera, across the Pyrenees, and through El Castillo in northern Spain, before finally reaching the Portuguese Atlantic coast by 38,000 years ago.

2

(

Figure 3.1

)