Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (19 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

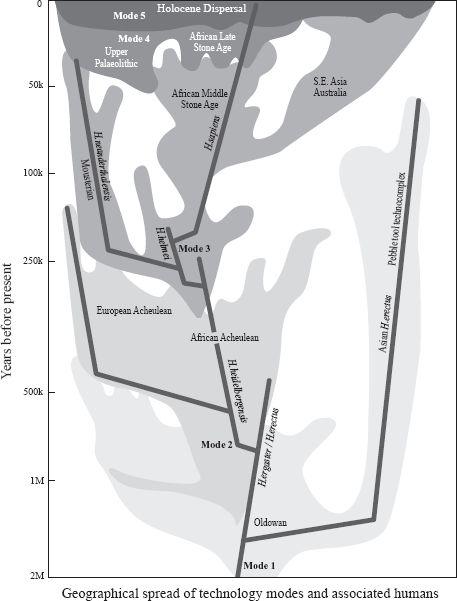

Figure 2.3

The worldwide spread in space and time of stone technology. Increasingly dark shading with time indicates successive spreads of Modes 1–5 (moving from Africa to Europe on the left; and to the Far East on the right). The human species associated with the spread of individual modes are superimposed as a branching tree.

American anthropologist–archaeologist duo Sally McBrearty and Alison Brooks have taken the argument of ancient African Middle Stone Age skills much further. In an in-depth interpretation of the origin of modern human behaviour entitled ‘The revolution that wasn’t’,

21

they challenge the orthodoxy of the 40,000–50,000-year-old ‘human revolution’. Instead, in parallel with but using a contrasting approach to Foley and Lahr, who see Mode 3 (Middle Palaeolithic) technologies as defining features of modern human behaviour, McBrearty and Brooks discuss the evolution of modern cultural behaviour in terms of the African Middle Stone Age. The latter ran roughly contemporary with the European Middle Palaeolithic up to the African Late Stone Age, with a prolonged fitful changeover starting sometime after 70,000 years ago. They see the African Middle Stone Age, starting with

Homo helmei

250,000–300,000 years ago, as a more dynamic and inventive cultural evolutionary sequence than its Middle Palaeolithic neighbour in Europe, anticipating many behaviours more characteristic of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Over several hundred years, they argue, humans in Africa had gradually assembled, by invention, an increasingly sophisticated cultural and material package of skills. Looking at the African record, only a few of these technical and social advances could be linked to biological milestones as

Homo helmei

were replaced by modern humans. Much more could be

attributed to purely cultural evolution, which has its own accelerating tempo.

Smart African tools

McBrearty and Brooks show that, in contrast to Europe, where the much-vaunted blade tools were a defining feature of the modern human arrival 40,000–50,000 years ago, blades were used off and on during the African Middle Stone Age for as much as 280,000 years, thus predating modern humans by almost a quarter of a million years.

22

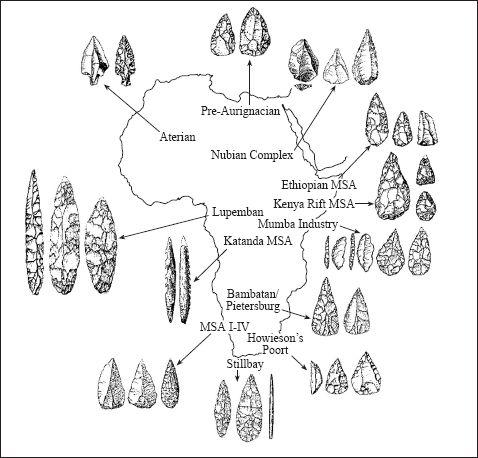

Another type of stone tool that flourished in the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic was the stone point. Points are basically flakes that have been retouched along both faces to make a point suitable for a spear tip. They have a 250,000-year history in Africa – much longer than that in Europe – and, as McBrearty and Brooks point out, show great regional diversity and sophistication there (

Figure 2.4

).

One specialized and precise type of stone tool that was first made in Africa turned up rather late in European prehistory: the microlith. Less than 25 mm (1 inch) long and blunted like a penknife along one edge, these tiny but accurately fashioned tools were made from small blades or segments of blades. They had a wide range of uses, particularly when set in complex hafted tools and weapons such as spears, knives, and arrows. A damaged individual microlith on such a weapon could easily be repaired or replaced. Regarded as Mode 5 – the ultimate in stone tool sophistication – they are the hallmark of the African Late Stone Age, turning up first in Mumba Rock Shelter, Tanzania, around 70,000 years ago. However, they appeared in Europe much later – mostly from after the last glaciation 8,000 years ago. The earliest consistent non-African record of microlith industries comes not from Europe but, significantly, from Sri Lanka, around 30,000 years ago, suggesting direct fertilization from Africa via the southern route (see

Chapter 4

).

23

The use of non-stone materials such as bone and antler to make tools and weapons was another novel skill claimed as a European first from 30,000–40,000 years ago. McBrearty and Brooks, however, point to ample evidence for bone tools in Africa up to 100,000 years ago. Not only that, but some of the first African bone tools were barbed points looking like harpoon tips (see

Figure 2.4

).

Figure 2.4

Map of the distribution of stone point styles found from the African Middle Stone Age. Note also barbed ‘harpoon tips’ from Katanda.

Another fascinating item in the human toolkit that dates back 280,000 years to the time of our grandparents

Homo helmei

is the

grindstone. Grindstones have nearly always had two completely different functions: to grind food, and to grind mineral pigments such as red and yellow ochre from lumps of rock. The latter application is much more relevant to the story of our intellectual evolution.

24

African artists

Pigment use has been regarded as another hallmark of the European Upper Palaeolithic,

25

so its appearance up to 280,000 years ago, in Africa, shows that the overemphasis on the beautiful Chauvet paintings as a first sign of symbolic behaviour has blinded us to the same stirrings of the mind in our more distant ancestors. Pigment was used so heavily in Africa up to 100,000 years ago that mining for minerals such as haematite was on what might be called an industrial scale. Quarrying began in Europe only 40,000 years ago. At one African mine, at least 1,200 tonnes of pigment ore had been extracted from a cliff face.

26

Some anthropologists and archaeologists get excited about the systematic use of pigment because they believe it to be early evidence, along with burials, for symbolic behaviour. Pigments were used for painting of walls and objects, for body painting, for use in burials, and to cure hides. Neanderthals used pigment, although the dating of finds seems to indicate that they acquired the use by cultural diffusion from early moderns. Sadly, we shall never know how much body hair Neanderthals evolved to combat the cold, but this could have reduced the ease and practicality of body-painting.

Both vegetable and mineral pigments were used by Upper Palaeolithic humans, but much of the clear evidence for vegetable pigments during the African Middle Stone Age will have decayed over time. Actual evidence of representational painting is also limited by time, particularly in Africa, which possesses far fewer limestone caves of the sort in which the Lascaux and Chauvet paintings have

been preserved. A curious point about Chauvet Cave, the earliest of European artistic canvasses, is that it represents the best we know of Palaeolithic art. With its extraordinarily realistic and imaginative action paintings, some of which exploit pre-existing physical features such as rocky outcrops for dramatic effect, Chauvet does not look like the first faint glimmerings of symbolic consciousness. What we see is a fully mature style, a confident peak from which later cave painting could only go downhill.

27

However, the first clear evidence of representational painting was not found in Europe but in a cave in Namibia, in southern Africa, dated by its Middle Stone Age context to between 40,000 and 60,000 years ago, thus preceding European painting (see

Plate 11

). Haematite ‘pencils’ with wear facets have also been found in various parts of southern Africa, dating from more than 100,000 years ago. This sort of evidence in itself again contradicts the European location for the ‘Human Symbolic Revolution’. As McBrearty and Brooks point out, painting could have an even greater antiquity in Africa, but the direct evidence has now perished or remains to be found when the same intensity of European research is applied to African sites.

28

Recognizable pictures of people, animals, and things need not be the first evidence for symbolic representation in any case. Regular scratches, cross-hatching, and notching of pieces of stone or mineral pigment blocks are likely to have had some symbolic purpose. Such artefacts appear in the African record from 100,000 years ago. Arguably the earliest evidence of such deliberate patterning of stone comes from sandstone caves in India around the Lower–Middle Palaeolithic transition, anywhere between 150,000 and 300,000 years ago. Australian archaeologist Robert Bednarik argues, controversially, that a number of meandering scored lines and cupules (shallow depressions on a rock face) in the Bhimbetka caves near Bhopal are the earliest evidence of symbolic art anywhere.

29

African ornaments

Personal ornamentation, for instance with beads and pendants, is claimed by archaeologists to show the novel sophistication of ritual and symbolic practices in the European Upper Palaeolithic. There is evidence for body ornamentation in Europe used by fully modern humans from about 40,000 years ago, but it was a particular feature of the Gravettian cultures that emerged about 30,000 years ago although there is evidence for it from 40,000 years ago. One of the most dramatic examples of such body decoration was found in a grave site 200 km (125 miles) east of Moscow at Sunghir. Here, 24,000 years ago, very close to the approaching ice sheets of the imminent glacial maximum, two graves were dug for three occupants, an old man and two children. They were all dressed in garments richly decorated with thousands of ivory beads (see

Plate 12

). Ivory bracelets, wands, animal figurines, and pendants completed the adornment.

30

McBrearty and Brooks have shown that personal ornamentation in Africa predated that in Europe by tens of thousands of years. They cite a perforated shell pendant, buried with an infant, dated to 105,000 years ago in South Africa, and other decorations and drilled pendants dated back to at least 130,000 years ago in the African Middle Stone Age. Ostrich-shell drilled beads are a feature of the African Late Stone Age and may go back to 60,000 years.

31

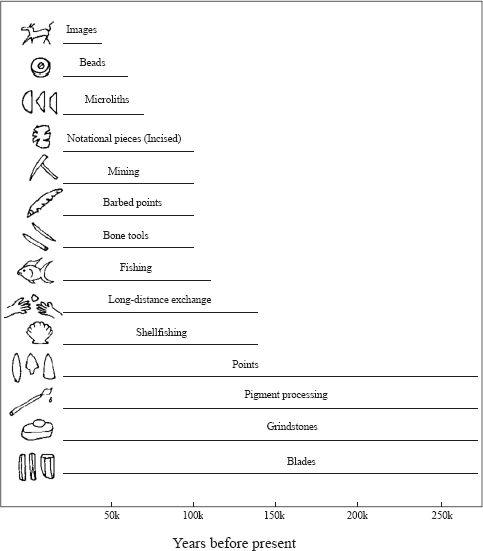

As we can see from

Figure 2.5

(which summarizes the evidence for the rather gradual acquisition of the elements of ‘modern’ culture over the past 300,000 years), using pigment, making symbolic marks on rocks, and fashioning blades and points were not actually inventions of modern humans at all. These skills and symbolic behaviours originated over 250,000 years ago – rather early on in the history of our archaic ancestor. More perishable evidence of complex culture, such as painting and beads, are still found in Africa from tens of thousands of years before the first such signs in Europe. Mining, bone tools, and bone harpoons appear from 100,000 years ago. In all these later instances the skills were chronologically and clearly associated with moderns.

Figure 2.5

Modern behaviours and evidence of their time depths of acquisition in Africa over the past 300,000 years. Four out of fourteen are present before modern humans, and the majority before the European Upper Palaeolithic.