Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (14 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Before looking at the archaeological evidence for that move, it might help to establish whether there was a precipitating climatic event, as in so much of our prehistory. Could a transient increase in the severity of glaciation have brought the sea level at the Gate of Grief to a point where our ancestors could have walked across from reef to reef? The increasing aridity of the East African coast might have reduced available drinking water, thus making the rather wetter monsoon conditions on the southern Yemen coast more attractive to the beachcombers. A ford across to Arabia might have been just the inducement to overcome any remaining fears of the neighbours. The latter, in turn, perhaps lacking beachcombing skills, may have left southern Arabia altogether because of the drought.

In spite of the attractive biblical allusion of this scenario, the problem with a dry exodus across the mouth of the Red Sea 60,000–90,000 years ago is that oceanographic evidence denies that the Gate of Grief was ever completely dry during our time on Earth.

Such an event nearly happened three times during major glaciations of the past half million years: 440,000 years ago, 140,000 years ago, and at the last glacial maximum 18,000 years ago.

37

The strait was very much narrower during glacial periods, allowing easy island-hopping across the shallows and the reef islands of the Hanish al Kubra, at the northern end of the isthmus. As we have seen, this must have been where Asian

Homo erectus

crossed, so it should not have been much of a problem for our pioneers to complete the journey to Australia within a few thousand years. Although the Red Sea did not part, there was a major cold event around the time of our first exodus from Africa (

Figure 1.7

). Measurements made on the Greenland ice cap show that the second-coldest time of the last 100,000 years was between 60,000 and 80,000 years ago.

38

At its coldest, 65,000 years ago, this glaciation took the world’s sea levels 104 metres (340 feet) below today’s levels. The way in which this sea lowstand (as it is called) was measured in the Red Sea holds an unexpected clue for what might have been the stimulus to move.

Oceanographers have been able to measure interglacial sea-level highstands by looking at coral reefs. Sea-level lowstands which occurred during glacial maxima are more difficult to confirm. Eelco Rohling, an oceanographer at Southampton University, has found a way to use the Red Sea to overcome this problem. He measured prehistoric levels of Red Sea plankton. During a glacial maximum, the Gate of Grief approaches closure and the Red Sea becomes effectively isolated from exchange with the Indian Ocean. Evaporation causes the Red Sea’s salinity to increase so much that plankton, the base of the marine food chain, disappears. During an interglacial period, like now, the high sea level allows the Red Sea to flush out its salt, and sea life can start again. Sea-level lowstands like the one 65,000 years ago did not completely block the mouth of the Red Sea, so the plankton, although severely affected, did not completely disappear. The low level of plankton allowed Rohling and colleagues

to improve the previous estimates for the sea-level depression at this time.

39

Depression of plankton is worsened by low oxygen levels and high water temperatures in the shallows, as happens near beaches at Abdur in Eritrea and at the mouth of the Red Sea. Low levels of plankton in the Red Sea are, in turn, likely to have affected the success of the beachcombers. By contrast, the beaches of the Gulf of Aden just across the water in the Yemen were outside the Gate of Grief and had nutrient-rich, oxygenated upwelling water from the Indian Ocean. In other words, over on the southern Arabian coast the beachcombing conditions were probably excellent.

40

So perhaps dwindling food resources on the western shores of the Red Sea, attractive beaches on the Gulf of Aden, and cool wet Yemeni uplands for refuge were what spurred our ancestors to take their momentous step. The question still remains of when: did they wait until the sea levels were lowest and the beachcombing was at its worst, 65,000 years ago, or did they move earlier, when things first began to deteriorate? Again, the Red Sea plankton may give a clue. Plankton and sea levels did not decline evenly between 100,000 and 65,000 years ago. Instead there was a short, sharp depression of both at 85,000 years ago, with sea levels falling to 80 metres below present, followed by an equally dramatic and brief improvement 83,000 years ago.

41

Maybe that 85,000 year old dip was the spur that set our ancestors on their beachcombing trail.

Evidence of another great climatic catastrophe during that sea-level trough comes from cores drilled in the Arabian seabed.

42

This was the volcanic eruption of Toba in Sumatra, 74,000 years ago. Known to be by far the biggest eruption of the last 2 million years, this mega-bang caused a prolonged nuclear winter and released ash in a huge plume that spread to the north-west and covered India, Pakistan, and the Gulf region in a blanket 1–3 metres (3–10 feet) deep.

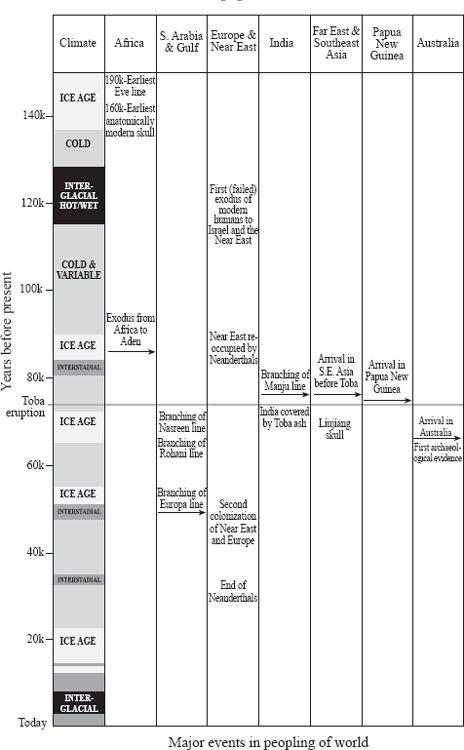

Figure 1.7

Timeline of climatic events and human expansions. The interglacial 125,000 years ago allowed the first northern exit. A climatic downturn at 85,000 years affected Red Sea salinity and may have prompted the southern exit. Toba’s explosion caused genetic bottlenecks both in and outside Africa. An ice age at 65,000 years then allowed access to Australia, while two clusters of interstadials from 50,000 years allowed colonization of Europe.

If our ancestors left Africa 85,000 years ago, their descendants would have anticipated the Toba explosion in Sumatra by 11,000 years (see

Figure 1.7

), and beachcombers around the Indian Ocean would have been in direct line for the greatest volcanic ash fall in the whole of human existence. The Toba eruption is thus a valuable date mark, since the ash covered such a wide area, is accurately dated, and can be identified wherever an undisturbed layer of it is found.

Malaysian archaeologist Zuraina Majid has explored the remains of a modern human culture in a wooded valley in Perak State, near Penang. A continuous Palaeolithic tradition known as the Kota Tampan culture goes back tens of thousands of years there. At one site, tools from this tradition lie embedded in volcanic ash from Toba.

43

If the association with modern humans is confirmed, this means that modern humans got to Southeast Asia before the Toba eruption – more than 74,000 years ago. This, in turn, makes the 85,000-year-old exodus more likely. Equally, genetic and other evidence for a human occupation of Australia by 65,000 years ago fits this scenario. The Toba event specifically blanketed the Indian subcontinent in a deep layer of ash. It is difficult to see how India’s first colonists could have survived this greatest of all disasters. So, we could predict a broad human extinction zone between East and West Asia. Such a deep east-west division, or ‘furrow’, is still seen clearly in the genetic record.

How does such an early date for the exodus fit with the genetic data? This is perhaps the most controversial and exciting part of the story. The short answer is that the genetic dates and tree fit the early exodus well (see

Chapters 3

and

4

). This also resolves the question I left hanging earlier about the origins of the Europeans: why it was

that Europe was colonized only after 50,000 years ago, yet arose from the same maternal ancestor as the Australians and Asians.

The first Asian Adam and Eve clans

As we saw above, a small number of founding Eve clans from Africa landed in the Yemen and became isolated from Africa. After many generations these lines eventually drifted down to just one mitochondrial Out-of-Africa Eve, otherwise known by the rather dull technical label L3. L3 soon gave rise to just two daughter female clans: Nasreen (N), and a sister clan, Manju (M) (see

Figure 1.4

).

Manju’s most ancient and diverse family is found in India, and Nasreen, for her part, was the only mother for Europeans – there being virtually no daughters of Manju in West Eurasia. Both Nasreen and Manju’s descendants are now, however, found in every other part of the world except West Eurasia (see

Appendix 1

and

Figure 0.3

). This fact on its own confirms that every non-African in Australia, America, Siberia, Iceland, Europe, China, and India can trace their genetic inheritance back to just one line coming out of Africa: it confirms that there was only one exodus. After the exodus, it seems, L3’s own unique African identity went the way of genetic drift and was lost except for a few local remnants, leaving just Nasreen and Manju and their daughters. We can thus trace every modern non-African descendant waiting at a shop counter in, say, Outer Mongolia, Alice Springs, or Chicago, back to that first out-of-Africa group.

There are a couple of exceptions that prove the rule. One of these is U6 (already mentioned), who moved back from the Levant into North Africa. The other is M1, who moved back across the Red Sea into Ethiopia about the time of the last ice age. How do we know that? Some exciting recent work by Estonian geneticists Toomas Kivisild and Richard Villems has showed that M1 does not go back as far in Africa as does the Manju clan in Asia.

44

In other words, M1 was a more recent recolonization of East Africa back from Asia.

Eve’s daughter line Manju is found only in Asians, not in Europeans. When we look at the oldest Manju branches in Asia we find a date of 74,000 years for the Manju clan in Central Asia, 75,000 years in New Guinea, and 68,000 years in Australia. India, as I have said, has the greatest variety of Manju sub-branches and may even have been the birthplace of Manju from L3; one Indian subclan alone (M2) has a local age of 73,000 years.

45

When we look at the genetic trail of our fathers, written in the Y chromosome, we see a similar picture. Of all the African male lines present before the exodus, only one gave rise to all non-African male lines or clans. This ‘Out-of-Africa Adam’ line gave rise to three male primary branches outside Africa, in contrast to the two female ones (Nasreen and Manju). Known to geneticists as C, D/E (or YAP), and F, I have chosen for simplicity to call these three clans Cain, Abel, and Seth after Adam’s three sons (see

Appendix 2

). As with Out-of-Africa Eve’s line, there are also modern day sub-Saharan African representatives. In Adam’s case this is Abel’s line, which has both an Asian and an African/West-Eurasian branch. The latter has a high representation, particularly in Bantu peoples, who recently and dramatically expanded from the north to the south of Africa. To keep things simple at this stage, however, I will leave more detailed discussion of Adam’s three sons to

Chapters 3

–

7

.

The origins of Europeans

The genetic tree tells us something clear and quite extraordinary about Europeans and Levantines: they came, not directly from Africa, but from somewhere near India in the south. Their matriarch, Nasreen, was probably the more westerly of Eve’s two Asian daughters to be born along the coastal trail. She is different from Manju in that her daughters are found among non-Africans throughout the world, in Eurasia, Australia, and the Americas. This difference from the Manju clan, which is absent from Europe and the Levant, means that the separation of Nasreen into Easterners and

Westerners could have happened near where the beachcombers reached India. By genetic dating, Nasreen’s Asian and Australian descendants are at least as old as Manju.

46

The most likely point on the route for the birth of Nasreen is the Arabian Gulf. At that dry time it was not a gulf at all, but an oasis of shallow freshwater lakes fed by underground aquifers and the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. There in the south, Nasreen had a daughter, Rohani, 60,000 or more years ago. This beautiful desert refuge must have survived throughout the following tens of thousands of years, for, although these western clans clearly originate in the south, we find no genetic or archaeological evidence of Nasreen’s and Rohani’s daughters having arrived in Europe or the Levant until 45,000–50,000 years ago.

As always, there is a climatic reason for the late colonization of Europe by Nasreen’s daughters from the Gulf region, and we can find it in cores drilled from the seabed off the Indian coast, in the submarine delta of the Indus. As explained above, access between Syria and the Indian Ocean was always blocked by desert during glaciations. Almost exactly 50,000 years ago, however, there was a brief but intense warming and greening of South Asia, with monsoon conditions better than today. This climatic improvement can be detected as a carbon-rich layer in the undersea delta of the Indus.

47

Since the warm spell lasted perhaps only a few thousand years, geologists call it an ‘interstadial’ rather than ‘interglacial’, but the effect on the dormant Fertile Crescent of Iraq was the same.