Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (12 page)

All this adds up to a view of both Europe and North Africa as recipients of ancient migrations from farther east. In other words, there is no evidence of a first northern exodus from sub-Saharan Africa into North Africa – but rather the opposite. Just where in the East these ‘Nasreen’, ‘Rohani’, and ‘Europa’ branches came from, we shall see shortly.

Just one exodus

The strongest evidence against the north as the primary route for Europeans, or for any other modern humans for that matter, comes again from the structure of the maternal genetic tree for the whole

world. As can be seen in

Figure 1.4

, only one small twig (Out-of-Africa Eve) of one branch, out of the dozen major African maternal clans available, survived after leaving the continent to colonize the rest of the world. From this small group evolved all modern human populations outside Africa. Clearly, if there was only one exodus, they could have taken only one of the two available exit routes from Africa. I cannot overemphasize the importance of the simple and singular fact that only one African line accounts for all non-Africans.

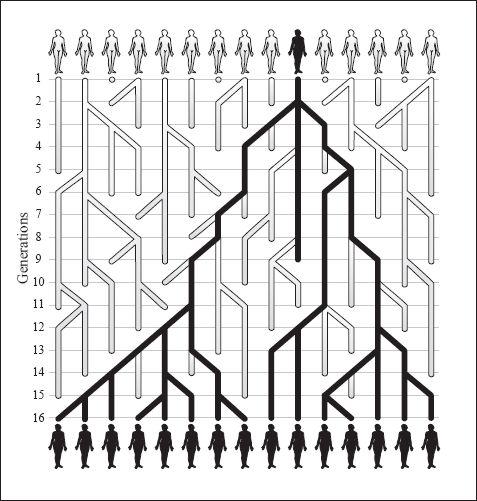

In any exodus from Africa there would have been a mix of different potential founder genetic ‘Eve’ lines. The same applies for any random group of people. Yet only one of these genetic lines survived. How this came about holds the proof for how many sorties from Africa were successful. Let us say there were fifteen genetically different types or lines of mtDNA that left Africa in a particular group (it could be more or less, as in

Figure 1.5

). This is a realistic number; even today there are fifteen surviving African maternal lines older than 80,000 years (see

Appendix 1

). These could be viewed as fifteen different kinds of marbles in a bag. From those fifteen lines only one mitochondrial line would, over many generations, become the Out-of-Africa Eve line or the common ancestral ‘mother line’ of the rest of the world. In other words, there would be only one kind of marble left. This random selection and extinction process is called

genetic drift

because the original mix of lines has ‘drifted’ towards one genetic type.

The mechanism behind drift is simple. From time to time, some mothers’ lines will die out because they have no daughters surviving to reproduce. These gene line extinctions are shown in

Figure 1.5

. In a small isolated population, this will eventually leave a single surviving ancestral line. Drift has strong effects in small groups. A common modern example of drift, seen through the male side, is that of small isolated Alpine or Welsh villages ending up after

generations with just one family surname – Schmidt or Evans, perhaps – on all the shopfronts.

Figure 1.5

Genetic drift. Diagram to show how, over the generations in a small isolated population of constant size (e.g. 100–400), there is a tendency for natural variation in reproductive success to reduce diversity – so from many varieties of mtDNA to a few or just one line (highlighted in black). Tracing back from the 16th generation here shows they all have the same ancestral mother.

If we now take two identical African exodus groups and isolate them in different regions (two bags of marbles in our analogy), each group will drift down to one gene line. Because drift is due to random extinction, the two groups will not usually both drift to the

same line (the chances of this happening are 1 in 15 if there are equal numbers of each type to start with). If we then take two different groups coming out of different parts of Africa (the northern route and the southern route – see below) at different times, tens of thousands of years apart, they would not be at all similar and would represent a completely different selection of African lines. Again, the two groups would be even less likely to drift down to the same line.

It does not require much statistical knowledge to see that the odds against two such independent small migrant groups moving out at different times and in different directions from Africa, and each then randomly drifting to exactly the same maternal gene line, are vanishingly small. It would be the same as ending up with exactly the same kind of marble in each bag. Had there been two migrations, there would inevitably be at least two Eves for non-Africans. In other words, the genes confirm to us that if only one mitochondrial gene line survived outside Africa, there was only one group that made it out of Africa to populate the rest of the world. That same small group eventually gave rise to Australians, Chinese, Europeans, Indians, and Polynesians. And their genes came out of Africa at one point in time.

Clearly, with this unitary argument, if the northern route could not give rise to Australians, then logically nor could it give rise to anyone else outside Africa. But before rejecting the northern route and exploring the feasibility of the single southern route, we should pinch ourselves and ask whether the rest of the genetic evidence really is consistent with this single exodus view. The short answer is yes, when we look at genetic markers other than mitochondrial DNA. If we look at the Y chromosome, we find that all non-Africans belong to only one African male line, designated M168. Using markers passed down through both parents, several studies have again shown evidence for only one expansion out of Africa.

21

Another issue that is very relevant here is the prediction of dates.

When we look at the founding African genetic line, Out-of-Africa Eve, which gave rise to non-Africans, we find an age of around 83,000 years

22

(see

Figure 0.3

). This does not fit with the archaeological and genetic evidence of a much later colonization of the Levant and Europe from only 50,000 years ago.

In contrast to the very derived nature of genetic lines in North Africa, there is another African region that holds an extraordinary diversity of genetic lines, close and parallel to the very roots of the out-of-Africa branch. This is Ethiopia, with its green hills standing out among the surrounding desert and dry savannahs of the Horn of Africa. But Ethiopia is to the south-east of the Sahara, literally at the gates of the southern route. Geneticists are now in a race to study Ethiopians, some of whom may be descended from the source population of that single exodus. This leads us now to look at the southern route.

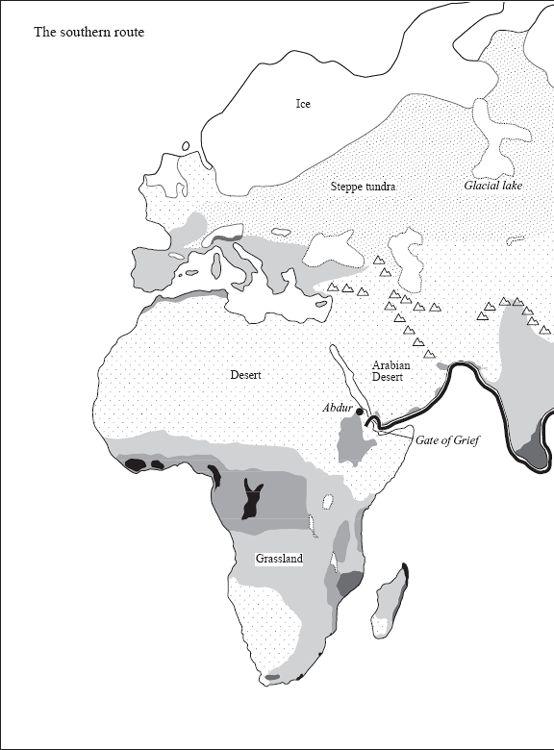

The southern route

To fully understand the alternation of corridors that potential emigrants from Africa had to contend with, we have to go back to the first human to leave Africa. Millions of years ago, when the super-continent Pangaea was in the process of breaking up, Africa shivered and cracked her flank. This huge fault in the Earth’s crust connects to the rift valley system of East Africa. Its most visible effect is a deep cleft between Africa and Arabia – the Red Sea. At the northern end of the Red Sea now lies Suez, and at the southern end is an isthmus, 25 km (15 miles) wide and 137 metres (450 feet) deep, known as the Gate of Grief (Bab al Mandab) from its numerous reefs (see

Plate 7

). Two million years ago, Africa was still joined to Arabia and the strait was dry. A wide range of Eurasian and African mammals were able to cross between Arabia and Africa at both the northern and southern ends of the Red Sea. At that time, however, Africa was already moving away from Arabia at a rate of 15 mm per year,

gradually opening the isthmus and eventually closing the southern gate out of Africa.

Recent evidence shows that one of the last mammals to walk out of Africa, before the Gate of Grief finally flooded and closed, was our second cousin

Homo erectus

(see

Plate 2

), carrying with them a few basic pebble tools. At this stage, since both the northern and southern gates were open, our cousin spread rapidly eastward through India to East Asia and also up through the Levant, reaching Dmanisi in the Caucasus by 1.8 million years ago.

23

The flooding of the Gate of Grief was not the only barrier raised to mammalian movement into Asia. Two more hurdles had been erected. The first of these, as referred to above, was a long range of mountains, the Zagros–Taurus chain. These had been pushed up in the previous few million years at the same time as the Himalayas. Stretching from Iran to Turkey, this rocky barrier has effectively prevented access from the Levant to India, Pakistan, and the Far East ever since humans first moved out of Africa. The second land barrier separated the northern and southern gates from each other (

Figure 1.6

) and is known today as the Arabian Desert, or by such grim terms as ‘the empty quarter’. One of the driest deserts in the world, it increased in size to occupy the whole Arabian peninsula as our present ice epoch, the Pleistocene, began to bite 2 million years ago.

Ice ages mean cooler weather and less evaporation from the sea; this, in turn, meant less rain in the desert belt. In a really severe ice age, like the one we have just had 18,000 years ago, huge volumes of water are locked up in ice sheets over a kilometre thick. During a glacial maximum the sea level falls sufficiently for the normal water exchange between the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea to almost stop.

24

There have been two of these events in the past 200,000 years, during our own time on Earth, when the Red Sea effectively became an evaporating salt lake. Most of the plankton died off. Although the Red Sea was more or less sterile, there was still a very

narrow water channel of a few kilometres at the mouth, broken up by reefs and islands.

Like the greening of the Sahara, such extreme glaciations have been rare and rather short-lived. When they do happen, roughly every 100,000 years over the past 2 million, humans from Africa could easily make the southern crossing across the mouth of the Red Sea, with the aid perhaps of primitive rafts, island-hopping where necessary. (The raft option was of course not available to other big mammals.) Even when accessible like this, the main part of the Arabian Peninsula is not a very attractive prospect for emigrants, always being bone dry in the depths of an ice age. There are, however, green refuges in the Yemeni highlands above Aden. The south Arabian coast also benefits from the monsoons thus allowing the beachcombing trail towards the Gulf. Humans may have crossed out of Africa by this southern route at least three times in that past 2 million years.

25

After humans first walked across into Asia 2 million years ago, the desert barriers separating Europe and the Middle East from Asia were closed. Crossing from Africa by the southern route, they could move on and into India only by making their way along the coast, while those taking the northern route could only go into the Levant, the Caucasus, and Europe.

These complex corrals and barriers to migration into Asia set the pattern for the human colonization of the rest of the world. As each new version of the genus

Homo

arose in Africa, some tribes would take the northern route during a warm interglacial, while others would take the southern route during an ice age. The first humans to take the northern route during an interglacial, around 1.8 million years ago, reached Dmanisi in Georgia. To look at, they were perhaps closer to

Homo habilis

, the earliest and most primitive African human, than to their East Asian

erectus

contemporaries. Somewhere between early African

erectus

(

Homo ergaster

) and

Homo habilis

they have been assigned a new species name,

Homo georgicus

. This parallel colonization by two different early human species taking different routes supports the view that human exits from Africa before the closing of the southern route had more to do with opportunities of geography available to any African mammal than with some special behaviour of

Homo erectus

, as was previously thought.

26