Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (11 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Yet there is little other archaeological evidence in North Africa for the ancestors of the Cro-Magnons. Even the single child buried at Taramsa Hill in Egypt was found with Middle Palaeolithic stone tools that could equally have been made by Neanderthals and show no hint of the new technology about to explode into Europe.

The Australian problem

The greatest problem for the Eurocentric cultural agenda underlying the northern route out of Africa, however, is posed by the Australians, who evolved their own singing, dancing, and painting culture far earlier than, and with no help from, the Europeans. Which part of Africa did they come from? What route did they take?

Were they part of the same exodus that gave rise to the Europeans? And, above all, how did they get to Australia so much earlier than the Europeans got to Europe? This conundrum has generated a number of clever rationalizations.

Clearly, none of these questions is easily answered by a single northern exodus to Europe 45,000 years ago, followed by a spreading out into the rest of the world, as suggested by Chicago anthropologist Richard G. Klein in his classic

The Human Career

. The dates are too late for the finds from Australia, and therefore wrong for that theory. The zoologist, Africa expert, artist, and author Jonathan Kingdon has gone even further and argued that the first ‘failed’ northern exodus to the Levant, which took place 120,000 years ago, had already spread eastward from the Levant to colonize Southeast Asia and then Australia before 90,000 years ago. This solution thus allows only one early exodus from Africa – via the northern route. Chris Stringer has taken the simplest approach by proposing that Australia was colonized independently long before Europe by a separate exodus round the Red Sea.

14

Like Chris Stringer, the Cambridge team of archaeologist Robert Foley and palaeontologist Marta Lahr also argue that a North African refuge, expanding via the northern route through the Levant, was the crucible for Europeans and Levantines. They have no problem with the number of movements out of Africa, postulating instead that there were multiple breakouts from refuges scattered across Ethiopia and North Africa. This view takes into account the interglacial population expansions in Africa 125,000 years ago. Lahr and Foley see the return of the dry ice-age conditions in effect splitting the African continent into isolated human colonies corresponding to islands of green (see

Figure 1.6

) that remained separated from one another by intervening desert for the next 50,000 years. Under the Foley–Lahr scheme, the ancestors of the East Asians and Australians could have broken out from Ethiopia and moved east across the Red

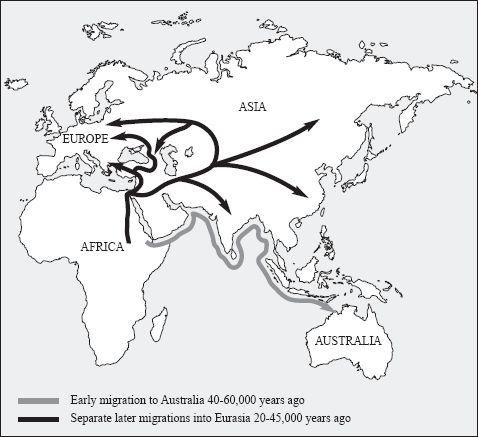

Sea at any time. They would thus have had to take the southern route independently of the ancestors of the Europeans. Foley and Lahr have recently taken this north-and-south viewpoint further by teaming up with American Y-chromosome expert Peter Underhill in a recent genetic-prehistoric synthesis. They describe an early exodus to Australia via the southern route, with the main out-of-Africa movement going north later via Suez and the Levant to Europe and the rest of Asia (

Figure 1.3

) between 30,000 and 45,000 years ago.

15

Figure 1.3

The multiple-exodus hypotheses. Most recent out-of-Africa syntheses argue for at least one northern exit to Europe and further to the rest of Asia within the past 50,000 years, while acknowledging the possibility of an earlier southern route to Australia (Stringer et al. (1996, 2000),

14

Lahr and Foley (1998),

15

Underhill et al. (2001)

15

).

So, the insistence by many experts that Europeans came out via North Africa can be seen to depend on various rationalizations. These include North African refuges and either multiple out-of-Africa migrations or an early onward migration from the Levant towards the Far East. There are problems with all these rationalizations in their attempt to preserve the hallowed northern route for Europeans. Taking the most straightforward first, Jonathan Kingdon has suggested that the world was peopled by a single early northern out-of-Africa movement during the Eemian interglacial 120,000 years ago.

16

Since many of the desert corridors in Africa and West Asia were green at that time, the would-be migrants to Australia could have walked briskly eastward, straight from the Levant to India. They could then have taken a rest in green parts of South Asia before proceeding to Southeast Asia, arriving by 90,000 years ago, and then colonizing Australia. (By ‘South Asia’, I mean those countries between Aden and Bangladesh that have coasts facing the Indian Ocean. This includes the countries of Yemen, Oman, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, and the southernmost parts of those that border the Arabian Gulf: Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Beirut, the United Arab Emirates, and Iran.)

As evidence of an ancient skilled human presence east of the Levant, Jonathan Kingdon points to abundant Middle Palaeolithic stone tools found in India starting from 163,000 years ago. The problem with this view is that there is no skeletal evidence for modern human beings anywhere outside Africa of that antiquity. Kingdon acknowledges that these tools could easily have been made by late pre-modern or archaic humans (the Mapas, as he calls them) who were in East Asia at that very time.

Clearly, to get to Australia, Australians must have gone through Asia, but this kind of logic is still no proof that Anatomically Modern Humans migrated across Asia before 90,000 years ago, let alone 120,000–163,000 years ago.

The eastern barriers

There is another problem with Kingdon’s 90,000–120,000-year bracket for the colonization of Southeast Asia. If his early migration into Southeast Asia had left the Levant any later than 115,000 years ago, they would most likely have perished in the attempt. Analysis of human and other mammalian movements from Africa to Asia over the past 4 million years suggests that, except during an interglacial, there were a variety of obstacles to movement between the Levant and the rest of Asia. When the world was not basking in the moist warmth of an interglacial, there were major mountain and desert barriers preventing travel north, east, or south from the Levant. To the north and east was the great Zagros–Taurus mountain chain, which combines with the Syrian and Arabian Deserts to separate the Levant from Eastern Europe in the north and the Indian subcontinent in the south.

17

Under normal glacial conditions this was an impassable mountainous desert. There was no easy way round to the north because of the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus.

As in Marco Polo’s time, the alternative overland route from the Eastern Mediterranean to Southeast Asia was to get to the Indian Ocean as soon as possible and then follow the coast round. To the south and east of the Levant, however, are the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and the only option was thus to follow the Tigris Valley round from Turkey and down the western border of the Zagros range to the Arabian Gulf (see

Figure 1.8

). But this route, through the Fertile Crescent, was also extreme desert outside interglacial periods and was therefore closed.

The practical impossibility of modern humans getting from the Levant or Egypt to Southeast Asia 55,000–90,000 years ago means that a northern exodus from Africa during that period could have given rise only to Europeans and Levantines, not to Southeast Asians or Australians. Now, Europe and the Levant were not colonized until around 45,000–50,000 years ago, and Australia, on the other

side of the world, was colonized well before then. This in turn means that, in order to preserve the northern route for Europeans, Chris Stringer, Bob Foley, and Marta Lahr have all had to postulate separate southern routes for Australians and even for Asians. This tangle is resolved by the genetic story.

What the genes say about the northern route

All such speculations have previously rested on an archaeological record consisting of a few inaccurately dated bones separated by huge time gaps. From the turn of the century, published work on the European genetic trail by scientists such as Martin Richards, Vincent Macaulay, and Hans-Jurgen Bandelt has changed all that and allowed us to examine the first leap out of Africa with a much clearer focus on the timing and location.

18

This work does two things. First, it confirms that the Levantine expedition over 100,000 years ago perished without issue, so that the first doomed exodus of modern humans, like the Neanderthals who in turn died out 60,000 years later, left no identifiable genetic trace in the Levant. Second, although sub-Saharan Africans may have much more recently left their genetic mark surviving in one-eighth of modern Berber societies, it reveals no genetic evidence that either Europeans or Levantines came directly from North Africa.

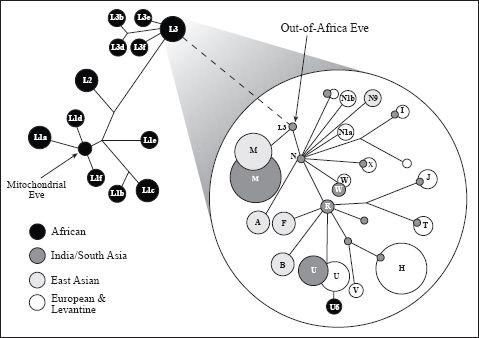

How do I know this? The construction of a precise genetic tree using mitochondrial DNA makes it possible to do more than just identify our common ancestors.

Figure 1.4

shows our mitochondrial tree, starting at the base as many clans in Africa, then sending a single branch (L3) out into South Asia (India). L3 became our Asian Out-of-Africa Eve and soon branched many times to populate Arabia and India, then Europe and East Asia. We can date the branches in this tree and, by looking at their geographical distribution, show when and where the founders arose for a particular prehistoric migration. On a grander scale, this method is how the out-of-Africa hypothesis was proved.

Using this approach, we can see that Europe’s oldest branch line, designated U (50,000 years old and shown in

Figure 1.4

), which I have called Europa after Zeus’ lover of the same name, arose from somewhere near India out of the R branch, which I have called Rohani after its Indian location. R, in turn, arose out of the N branch, which I call Nasreen, and which arose from the Out-of-Africa Eve twig, L3. If Europeans were derived from North African aboriginal groups such as the Berbers 45,000 years ago, we would expect to find the oldest North African genetic lines deriving directly from the origin or base of the L3 branch.

19

Figure 1.4

A single expansion from Africa. Simplified network of mtDNA groups showing how only one of 13 African clans gives rise to all non-Africans. N (Nasreen) group is expanded to emphasize West Eurasian ramifications, while M (Manju) has no representation there and heavy presence in India. (For detail and dating of tree branches see

Appendix 1

.)

Instead, when we look at North Africans, in particular the Berbers, who are thought to be aboriginal to that region, we find the very opposite. North African lines are either more recent immigrants or very far removed from the root of L3. First, there is no evidence in North Africa for the earliest out-of-Africa branch nodes, Nasreen and Rohani. Those are found instead in South Asia – as shown in the figure. In fact, we find that North Africa has been populated mainly by recent southward migrations of typical European and Levantine genetic lines. The oldest indigenous North African mtDNA line, sometimes referred to as the Berber motif, is dated to have arrived from the Levant around 30,000 years ago, and is a solitary derived sub-branch (U6 – see the figure) of the West Eurasian Europa clan (West Eurasia being Europe and the Middle East). U6 shows every sign of having come

from

the Levant rather than the other way round. About one-eighth of maternal gene lines in North Africa come from more recent migrations from sub-Saharan Africa, and over half are recent movements south from Europe. Finally, the other daughter clan of Out-of-Africa Eve, the Asian M supergroup which is found in India, is completely absent from Europe, the Levant, and North Africa. This makes it extremely unlikely that North Africa could have been the source of Asians, as put forward in Jonathan Kingdon’s scheme.

20