Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (45 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Figure 7.4

North America during the last glacial maximum. At the LGM, no further movement was possible and the ancestors of sub-arctic Americans were locked into a Beringian refuge with drift down to one line A2. South of the ice, people carrying groups A, B, C and D could continue to develop diversity in language, culture and genes.

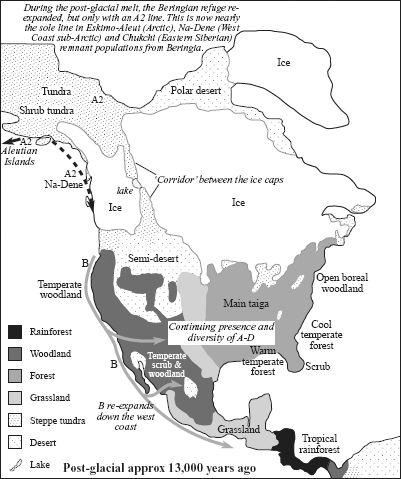

Figure 7.5

Post-glacial mtDNA re-expansions in North America starting from 13,000 years ago. In Beringia, the tundra area has increased and access to the Aleutians and south along the west coast has opened, allowing group A2 to reexpand among the Inuit-Aleuts and Na-Dene. The ice corridor is not quite open. Group B can also expand along further down the west coast and into the southwest.

For my money, the results obtained by Forster and colleagues are among the most important in clarifying dates in the complex story of American colonization. They also contained the first clear genetic evidence for the Beringian re-expansion as previously suggested by archaeologists. It is worth summarizing the conclusions. The first is confirmation that there were four main American founder mtDNA types arising from the four Asian groups A–D identified by Antonio Torroni and colleagues in 1993: A1 (leading to A2), B, C, and D1. Second, these four founders probably arrived in America before Clovis and before the LGM 18,000 years ago. Third, the homeland for the movement of these founders into the Americas was Beringia, not Asia.

This last point may sound like splitting hairs (or continents), since Beringia must ultimately have received its people from Asia, but this is not a fine point. What Forster and his colleagues are saying in effect is that from some time after it was first colonized, before the last ice age, until maybe the last thousand years of its existence, Beringia was effectively cut off from Asia and received no further Asian founders. The importance of this distinction will become apparent shortly. Beringia was the source of American lines both before the LGM (Amerinds) and during the Arctic/Subarctic re-expansion by the Na-Dene and Inuit-Aleut. The post-glacial re-expansion from Beringia only included A2 presumably because the ice age caused a near-extinction in the north, and a so-called genetic bottleneck that resulted in only one genetic line surviving.

Others have since come up with essentially similar scenarios or variations on the theme of an early migration(s) into the Americas taking in most if not all the founders before the last ice age.

46

The X line

Before we look at what the evidence has to tell us about whether this preglacial invasion was single or multiple, there is one more maternal founder line to consider. The fifth founder had an enigmatic identity, which has only fully emerged in the last few years. Appropriately, the name chosen for this extra founding line was X.

In 1991, Ryk Ward came up with four clusters. Two years later, Torroni and colleagues identified their own groups A, B, and C in three of Ward’s clusters and resolved the remaining types partly into their new D group; but they left the rest of Ward’s fourth cluster in an unresolved ‘others’ bin. Over the next couple of years, more research groups came to see that this other group was, as Ward had originally suggested, another cluster with a single origin – in other words, a fifth American founder line. Among them were Argentinian geneticist Graciela Bailliet and collaborators, and also mathematician Hans Bandelt and colleagues, who noted the likelihood of a fifth founder in connection with his new method of genetic tree-building. Forster’s re-analysis of American founders in 1996 defined and renamed this new American clan the X group. This confirmed that the fifth American founder and the European X group which Torroni identified in the same year had the same common X ancestor.

47

The American X group had a limited, northerly distribution, mainly in two separate Amerind-speaking cultural regions around the 50th parallel. The first of these cultural groups, in the Pacific north-west, were the Yakima of Washington State and the Nuu-Chah-Nulth. The latter is a fishing culture found on the western coast of Vancouver Island (and also on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State) with a cultural continuity of 4,000 years. These groups had rates of 5 and 11–13 per cent X, respectively. The other northern groups holding X types were the Sioux and the Ojibwa of the eastern woodlands around the western edge of the Great Lakes. The latter had rates of 25 per cent.

48

Could these X types in Native Americans have come from European female lines entering the tribal populations recently? Almost certainly not, since X was already present in pre-Columbian peoples of these regions. Ward’s original study had carefully excluded the possibility of significant European admixture in the Nuu-Chah-Nulth. In the case of the eastern woodlands Native Americans, direct evidence of X in pre-Columbian populations was provided by an analysis of ancient mtDNA from the prehistoric Oneota population of the nearby Illinois River region.

49

Kennewick Man: a pre-Columbian European connection?

This transatlantic DNA cross-match between Europeans and Native Americans has helped to fuel a chronic, rather dubious debate on who got to America first. The bone of contention is the problem of skeletal resemblances between ancient Americans and Europeans. Skulls of ancient Americans dating from 5,000–11,000 years ago have been studied for decades, and are known to be different from the skulls of later inhabitants, but it is not clear

why

they are different.

In 1996, the same year as the X founder was given her name and was linked with Europeans, two young men found a skull in the Columbia River at Kennewick, Washington State. American physical anthropologist James Chatters was called in by the coroner and was able to retrieve more of the skeleton. Embedded in the pelvis was a stone spear tip typical of the location and the period 4,500–8,500 years ago. The obvious antiquity of the leaf-shaped serrated stone point prompted the coroner to order radiocarbon and DNA studies.

50

From the start, it was obvious that the skull did not look like a typical modern Native American. This man, who had died aged between forty and fifty-five, had a long narrow skull with a narrow face with a jutting chin, and looked more like a European than the broad-faced, broad-headed individual that might have been

expected. James Chatters’ professional reconstruction (see

Plate 26

) looks strikingly like Patrick Stewart of

Star Trek

fame, although maybe it is the baldness of the reconstruction that enhances this impression. The trouble is that Kennewick Man was not Caucasoid. Some of his features can be described as Caucasoid, and others as Asian. The features that make Kennewick Man look like a European were seized upon by the press – and by white supremacists eager to claim that America had been colonized by whites a long time ago.

Kennewick Man’s teeth were Sundadont, suggesting Southeast Asian origins, and his eye sockets were also unlike those of Europeans or modern Native Americans. Intensive studies of combinations of his skull features revealed that the extant modern populations he most resembled were the Ainu and South Pacific peoples, including Polynesians.

51

Most striking of all was how unlike any peoples of the past 5,000 years he was. A lot of other things were learnt about Kennewick Man. He had suffered many injuries and bone fractures, and had enjoyed a diet rich in marine protein, such as salmon.

Radiocarbon dating confirmed the age of the skeleton to be 8,400 years.

52

The skeleton was then impounded by the US Army Corps of Engineers and became the object of a legal tug-of-war between different advocacy groups. In spite of this, several DNA labs attempted to extract DNA from the bones. For technical reasons, and contamination by modern DNA, they were unsuccessful, which is regrettable.

A successful DNA extraction and analysis could have provided us with any of several different results, most of which might not have answered everyone’s questions. Mitochondrial DNA, although it is useful for tracing movements of peoples, is but a small fragment of our genetic heritage. It does not tell us what we should look like. But it can often tell us where our maternal ancestors came from. For example, if in the unlikely possibility that uncontaminated Kennewick mtDNA had shown him to belong to one of the typical

European clans and to have close type matches in modern Europeans, that

would

have been some evidence of direct European input into North America. Most other possible outcomes are more likely to have been generally confirmatory of a Native American maternal origin, but this would not have proved that there had been no European colonists over 9,000 years ago. The lack of numbers of successful uncontaminated extractions is one of the many problems of studying ancient DNA; if uncontaminated DNA can be extracted, it is still only a single sample which tells us little about the rest of the population or their history. For these reasons, large-scale mtDNA studies of modern populations are generally much more informative than one-off ancient DNA investigations.

As if to tickle up the link between Kennewick Man and Europeans, his location on the Columbia River in Washington State near the American north-west coast put him near one of the two regions where the X group had been found, in particular near the Yakima tribe.

The Solutrean hypothesis

The idea of Europeans and European technology crossing the Atlantic in prehistoric times is not new, and was around long before Kennewick Man was found. One of the best known of such theories is called the Solutrean hypothesis (see

Figure 7.1

). Denis Stanford, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution, has been particularly identified with it.

53

The story goes that, at the height of the last ice age or maybe a little later, some hunters from the south-west European refuge area bordering France and Spain (see

Chapter 6

) took to their boats. They made it all the way from the European Atlantic coast, round the north Atlantic, to the east coast of America, where they became the Clovis people. The culture in the southwestern European refuge around the time of the LGM is known as Solutrean, and is famous for its beautifully worked bifacial points.

Solutrean points are argued to be a rare invention and similar to Clovis points or their precursors such as those found at Cactus Hill.

In support of the Solutrean theory is the habit, present in cultures both sides of the Atlantic, of driving herds of game over cliffs. This is hardly strong support since there is evidence for this practice even among pre-modern humans in China. It is also claimed that the highest concentration of the oldest Clovis points, which is said to be in the south-east USA, points to an Atlantic landing of immigrants. There certainly are problems with this theory, the most important of which are practical. The Solutrean cultures came before Clovis – and, as Vance Haynes so clearly demonstrated, Clovis did not appear until well after the LGM. If makers of Solutrean points had ventured round the northern Atlantic rim at the LGM, they would have to have skirted a coast that was ice-bound all the way round to New York.

54

Unfortunately for such wishful theories of Europeans having an early stake the Americas, as opposed to the view of them as much more recently responsible for the rape of the beautiful New World, the genetic story has no supporting evidence to offer. Rather the opposite, according to Atlanta geneticist Michael Brown, of the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. Confirming that the American X line was indeed a single fifth American cluster, Brown and colleagues estimated the age of arrival of the founder at 23,000–36,000 years ago, far too early for the Solutrean hypothesis or any other post-glacial entry. X was easily as ancient in America as were any of the other four founders. Five daughter X clusters had spread over North America into the different regions of the Great Lakes and West Coast both around the 50th parallel at around the same time.

55

There is no doubt that the American and European X lines have a common X ancestor, but they may have split from this ancestor as long ago as 30,000 years. If there had been a recent but pre-Columbian European admixture in the Americas, it should reveal

itself in Native Americans with typical European X subgroups or other commoner modern European lines, since X is quite rare in Europe. They are not to be found in America. The American X is therefore most likely to have arrived from Asia, the same way as the four other mtDNA founders (see

Figure 7.3

).