Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (41 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Thus was it ‘proved’, by the criteria of the time, that humans had entered the New World before 10,000 years ago. The old theory, of a more recent colonization, was overturned, and ‘the rest is history’ as far as many American archaeologists are concerned. But all was not quite as it should be in a nicely rounded drama. In the cycle of theories, this was the ‘good guy’ phase: authoritative dogma overturned by careful observation and persistence after frustration and denigration. In due course, the wheel would turn.

Subsequently, Clovis points were turned up throughout the continental United States. The conviction grew among American

archaeologists that these stone tools were the signature of the first human colonization of the Americas. After all, surely these first explorers were expert Upper Palaeolithic big-game hunters who had followed the mammoth trail across Beringia from Asia in the waning years of the last glaciation?

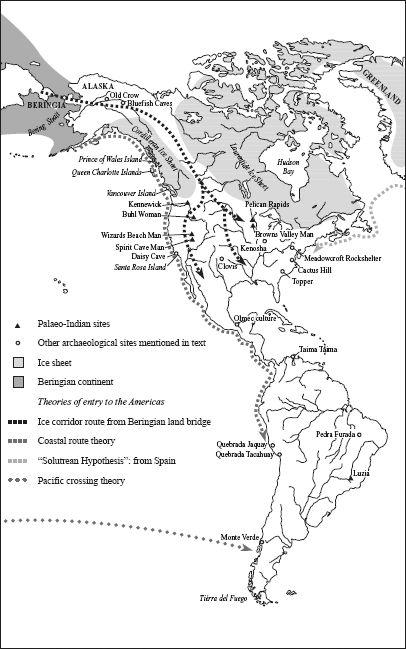

In 1964, American geochronologist C. Vance Haynes collected and linked together the dates of various Clovis-point sites using the new technology of carbon dating. These dates bracketed the earliest Clovis points to 11,000–11,500 years ago, and none was more than 12,000 years old. This latter age was significant for geologists, since they believed this was after the time when a corridor opened up between the two great melting ice sheets of North America and allowed passage from Alaska through Canada to the rest of the Americas (about 12,000–13,000 years ago). These two ice sheets, the Laurentide lying over Hudson Bay to the east and the Cordilleran covering the Rockies to the west, were so large that, on the evidence available in the 1960s, they seemed to span the continent.

5

(

Figure 7.1

.)

The Clovis-first theory had now matured into a complete and established orthodoxy. The argument went that humans could not have come into America before the Clovis points made their appearance because the way through was blocked by ice. All the Clovis dates pointed to a beginning that coincided with the opening of a vast corridor through the ice running from north-west to south-east from 13,000 years ago. Before this corridor opened, went the argument, no-one could have traversed the ice-sheets. Never mind that, even when it was open, the ice corridor was several thousand kilometres of barren Arctic desert and a lake requiring many packed lunches to traverse – this was the grand theory into which all elements could be fitted. The architects of the theory now became its high priests, and the theory was ripe for the next phase in the cycle of attack and defence of the new status quo. That attack and the fierce defence have now lasted over thirty years.

The strength, and at the same time the chief weakness, of the Clovis-first theory was that the earliest Clovis point had to be just after the opening of the ice corridor, and the ice corridor had to be just before the earliest Clovis point. Like a house of cards, nudge a key structural element and it will fall down. The key element was the insistence on the dates limiting the earliest entry to the Americas to after the opening of the ice corridor. If the occupation of North or South America could be pushed back just a few thousand years to a time when the corridor would have been closed, the theory would fall. In that case, the first entry would have to have been much earlier – before the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), and probably before 22,000 years ago.

Pretenders, heretics, or scientists?

Seen in this light, new pretenders bearing dates more than 1,500 years before Clovis would in effect be suggesting entry to the Americas before the ice age rather than after, a radically new theory. Although it would be marginally less persuasive, any evidence of occupation in South America, even slightly before Clovis and with different adaptive technology, would also make it unlikely that Clovis points identified the entry of the first Americans.

There have been plenty of new pretenders over the past few decades, whether we are talking about new archaeological sites with pre-Clovis evidence, or their advocates. In one review from 1990 I counted eighteen contender sites. This is a conservative estimate, perhaps half, of the total challenges mounted over the past two decades. Most of these pretenders have been routed by defenders of the Clovis-first orthodoxy in skirmishes characterized by attacks on scientific method, context, and observation. Only a few have survived the ‘critical’ broadsides fired by defenders of the orthodoxy, but they are still embattled. The most persistent and serious pretenders are the sites of Monte Verde in northern Chile and Meadowcroft Rockshelter in south-western Pennsylvania (see

Figure 7.1

). New recruits have joined their ranks, namely Cactus Hill in Virginia and Topper/Big Pine in South Carolina.

6

Figure 7.1

Theories of entry to America. At the LGM, access to the Americas was blocked by ice. Two window periods existed, one just before and one just after the LGM, when the Beringian land bridge was open and access was possible through the ice corridor or along the west coast. Also shown are other theories and sites mentioned in text. For clarity, present-day coastline shown.

The history of these claims and refutations is revealing of academe. The weapons of argument used by the defenders certainly appeal to scientific method, careful observation, avoidance of known sources of error, balanced logic, and reason; but the tactics of appeal are clearly biased, selective, petty, personal, and confrontational. In other words, the method of defensive attack is ‘sling enough mud in the form of possible errors or what if’s, and the good evidence all becomes tarred with the bad and can be dismissed’. This is reminiscent of a stock courtroom drama, where the witness is discredited by the clever, aggressive lawyer. That is, however, an adversarial, not a scientific approach. Furthermore, unlike the judge, archaeologists are not required to come to closure of a case or theory. They can and should remain open to different interpretations of the evidence. The ‘truth’ – whatever it is – is not on trial. Clovis-first and its defenders, however, may well be.

There is no particular a priori reason to think that America was first colonized after the last ice age rather than before, since sea-locked Australia, New Guinea, and even the Bismarck Archipelago and the North Solomon Islands were all colonized well before the LGM. On the other hand, there is every reason to assume that evidence is generally clearer the more recently it was set down, and that the global effects of the ice age destroyed much good evidence in North America. The fact, therefore, that there are a lot of Clovis points lying around from a few thousand years after the LGM, in good context, as opposed to the less well-provenanced evidence from before the LGM, does not

prove

that Clovis was first. It merely

disproves the preceding orthodoxy of the nineteenth century, that America was not colonized until 10,000 years ago. We should expect the preglacial evidence (if any) that questions Clovis-first to be weaker than Clovis itself.

Monte Verde

We can illustrate some of these points with the history of the Monte Verde controversy. Tom Dillehay of the University of Kentucky has been involved in the excavation of Monte Verde site in southern Chile since 1977, and he and his colleagues have amassed a considerable arsenal to use against the Clovis-first citadel. While there is some evidence for a very early occupation of Monte Verde, with split pebble tools dating to around 33,000 years ago, the ‘best’ evidence is dated much more recently. The site is a peat bog and has preserved a number of organic and other remains suggestive of human occupation: a footprint; wooden artefacts; structures that may be parts of huts; hearths; the remains of palaeo-llamas and mastodons, including cut bone; and seeds, nuts, fruits, berries, and tubers. Radiocarbon dating of the organic remains has yielded dates from 11,790 to 13,565 (average 12,500) years ago. Simple stone tools such as flakes and cobbles were also found.

7

Monte Verde lies 12,000 km (7,500 miles) south of the Alaskan ice corridor and, with an age of around 12,500 years, appears to antedate any Clovis site by a millennium. This raises the logical question of how anyone could have passed through the ice corridor after 13,000 years ago and still had time to travel so far south and then change culture.

8

This looked like powerful ammunition to use against the Clovis-first orthodoxy. Predictably, the Clovis-first camp fought back. To break the resulting deadlock, an independent set of referees was brought in.

In 1997 an invited group of the foremost Palaeo-Indian specialists, including sceptics such as Vance Haynes, gathered in Kentucky to hear Dillehay’s presentation, and then visited Chile for a site

inspection and further presentations. Each member of the group was handed a detailed site report published by the Smithsonian Institution. The group’s consensus report, published later that year in the academic journal

American Antiquity

, concluded that the site was an archaeological site and that the dates of occupation were around 12,500 years ago. A further article in

American Antiquity

by dating specialists, including Vance Haynes, confirmed the dates, freeing them from any suspicion of contamination with older carbon sources.

9

Then something happened which revealed the dispute in its true colours. This was now an academic turf war, with no place for the open-mindedness, objectivity, and reason expected of scientific peer review. Just when the Dillehay camp thought that the matter was closed, the wall of scepticism broken, and Monte Verde finally accepted by the establishment, a private archaeological consultant, Stuart Fiedel, published a long and stinging critique of the entire site report. Media drama intensified. Unconventionally, Fiedel chose to make his attack not in a peer-refereed academic journal but in a popular magazine,

Discovering Archaeology

.

10

The journal also ran responses from Dillehay’s group and supporters, as well as further sceptical comment and what amounted to a partial retraction by Haynes. This time the reaction came not just from the Dillehay supporters but from the establishment, in particular from

Archaeology

, the high-profile, high-circulation organ of the Archaeological Institute of America. The strength of the reaction is evident from the following extracts from both publications. First, from

Discovering Archaeology

:

If the case for the new idea or theory is deemed convincing, then the old paradigm quietly dies and the particular scientific field is better for it. In point of fact, however, and particularly in archaeology, it seems this admittedly idealized sequence of events rarely comes to pass. Instead, the whims of personality and pride are

frequently injected into the process, acrimony and

ad hominem

attacks set the tone of the debate, and objectivity is submerged in personal polemics. For these reasons, paradigms, especially old ones, die harder than Bruce Willis. This is clearly the case with the ‘Clovis-first’ or ‘Clovis primacy’ model, which is now more than 50 years old. (James Adovasio, ‘Paradigm-death and gunfights’

11

)

[Fiedel] blankets the whole in a patina of almost-conspiratorial mistrust and accusations, layered with all too-frequent snide remarks (e.g., ‘Dillehay’s Hamlet-like agonizing’). In that, he does his critique no favors. More to the point, the most useful, productive, and constructive procedure (and certainly the most open and fair minded) would have been to first send Dillehay a draft of the criticism for comment and clarification of what were the trivial/editorial problems, and then once the minor problems were dispersed with and the major issues clarified, submit the piece to a rigorously peer-reviewed academic journal. Fiedel did not do so. (David Meltzer, ‘On Monte Verde’

12

)

And from

Archaeology

:

Fiedel’s review is clearly biased and negative in tone. He ignores material that does not support his critical thesis and takes the more negative or improbable of alternative views of each case that he discusses. (Michael Collins, ‘The site of Monte Verde’

13

)

I’m irked at the carping tone of Fiedel’s commentary, and the ferreting out of meaningless conflict in interpretation over two decades of reporting on Monte Verde. Fiedel cops an attitude which, in my opinion, is entirely inappropriate. For my money, the Monte Verde research team should be celebrated, rather than henpecked, for their willingness to publish their findings in great detail and to share their misgivings about their own data . . . I think its [sic] a cheap shot to dredge up preliminary assessments

and press reports to attack the Monte Verde project. I still think its [sic] a good thing to change your mind (so long as you’re honest about it). I question Fiedel’s decision to rush his manuscript into print without first passing it by Dillehay and his colleagues for comment. Picking up on my earlier theme of self-criticism, its clear that the mishmash of Fiedel’s shotgun criticism could have been winnowed down through frank person-to-person communication with the Monte Verde principals. Once this interchange had occurred, we could have been presented with a concise summary of the real issues, unclouded by the chaff and attitude . . . Ambushing the Monte Verde team in this way inevitably raises questions over Fiedel’s motivations. Was the critique primarily concerned with clarifying the pre-Clovis possibilities at Monte Verde? Or was this just another carefully timed headline-grabber? Handled the way it was, who knows? (David Thomas, ‘One archaeologist’s perspective on the Monte Verde controversy’

14

)