Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (36 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

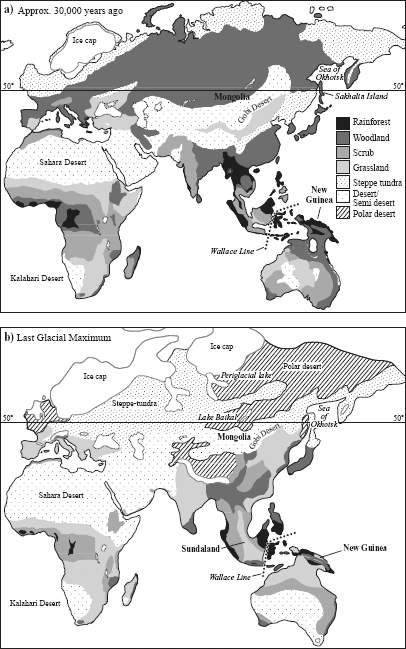

The LGM and its aftermath saw far more dramatic disruption and movement of northern human populations than at any time since. A glance at the world climate map 18,000 years ago begins to give us the reason why (

Figure 6.1b

). Huge areas of land became totally uninhabitable. For a start, the ice caps, some of them 5 km (3 miles) thick, clearly prevented the land they covered from being occupied. These white sheets were not laid evenly across the northern hemisphere. In Europe they mainly affected the central and northwestern regions. The British Isles, then part of the European mainland, were frozen down as far as Oxford in the south. Scandinavia will for ever bear the scars of the glaciers in its lakes and fjords and in the crustal depression now known as the Baltic Sea. Northern Germany, Poland, and the Baltic states bore the southern edge of the ice sheet, which extended north-east around the Arctic Circle across Finland and Karelia, into Archangel, and as far as the northern Urals. Farther south in Europe, mountainous regions such as the Pyrenees, the Massif Central, the Alps, and the Carpathians were ice-bound (sse

Figure 6.2

). As we shall see, however, Eastern Europe came off rather more lightly than the west.

Figure 6.1

World habitat changes at the LGM. Around 30,000 years ago (a), a huge open conifer woodland stretched from the Pacific to the Arctic and Atlantic coasts, allowing hunters to expand. At the LGM (b) this was reduced to a thin tongue of steppe tundra still occupied by hunters. While most of the world saw loss of habitable land Southeast Asia or Sundaland saw a dramatic increase.

Asia fared rather better than Europe. Most of North and Central Asia remained ice-free (see

Figure 6.1b

). Just to the eastern side of the Urals, a large cap covered the Tamyr Peninsula and spread some way to the south. The other part of the continent which could have sported an ice cap was the huge Tibetan Plateau much farther south, its great elevation making it a very cold place. Even here there is some doubt of the extent of ice cover, since surprising forensic evidence of the presence of humans in Tibet dates back to the LGM.

4

North America was particularly severely affected, with Canada, the Great Lakes, and the north-eastern states – in other words the entire northern two-thirds of the continent – weighed down by two massive ice sheets that connected on the east with the Greenland ice cap. Alaska, on the other hand, was then connected to Siberia by a huge ice-less bridge of now submerged land, Beringia, and to some extent shared Asia’s freedom from ice. The largest of the two American ice sheets, the Laurentide in the east, left its vast imprint as a deep dent in the Earth’s crust in the form of the great inland sea now known as Hudson Bay (see

Figure 7.4

).

In some places, in both Eurasia and America, huge lakes (known as periglacial lakes) surrounded the ice caps. The best-known remnants of these lakes are the Great Lakes of North America. The ice sheets themselves were not static, but flowed like the glaciers they were. Not only did these frozen rivers grind out new valleys and fjords, they also obliterated much evidence that humans had ever lived in the north.

Ice was not the only barrier to human occupation during the big freeze. The world’s deserts expanded to an even greater extent.

Around the ice caps, huge regions of North Eurasia and America became polar desert in which only the hardiest of plants and animals could survive. In Europe, the polar desert stretched east from the southern edge of England and due east across northern Germany, to the south of the Finno-Scandinavian ice sheet. The whole of the region from the Levant and the Red Sea to Pakistan, normally pretty dry, became a continuous extreme desert. Southern Central Asia, from Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan by the Caspian Sea in the west, through Xinjiang (north of Tibet), to Inner Mongolia in the east became continuous desert either side of the 40th parallel. This desert, which effectively replaced Guthrie’s Mammoth Steppe heartland, also split North and northern Central Asia from the whole of East and Southeast Asia.

Ice-age refuges

Africa’s human population suffered, as their forebears always had during every big freeze of the previous 2 million years. The Sahara expanded to cover the whole of North Africa; the Kalahari spread over most of south-west Africa; dry, treeless grasslands covered most of continent south of the Sahara. The great rainforests of Central and West Africa shrank into small islands in Equatorial Central Africa and the southern parts of the West African Guinea coast. In East Africa, the expansion of the dry savannah again separated humans in East Africa from those in South Africa. Only scrubby refuges surrounded by dry grassland were left as islands for the hunter-gatherers (see also

Figure 1.6

).

With North and Central Europe taking the lead along with America in building ice castles, we might wonder what happened to anatomically modern Europeans. Did they all leave or die, to be replaced later with another batch from the Middle East? Our cousins the Neanderthals had already disappeared 10,000 years before the LGM (see

Chapter 2

). Well, the archaeological record tells us that the pre-LGM Europeans hung on in there, but as happened in

Africa, their range contracted southward to three or maybe four ice-age temperate zones. The genetic trail also tells us an enormous amount about the origins and human composition of these glacial refuges, but first we shall go into the archaeological record to paint in some background.

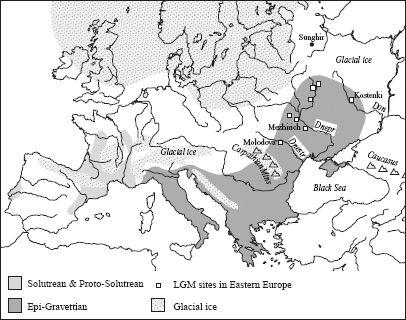

Most of Northern Europe was unoccupied at the LGM. There were three main refuge areas of Southern Europe to which the Palaeolithic peoples of Europe retreated (

Figure 6.2

). From west to east, the first consisted of parts of France and Spain either side of the Pyrenees, in the Basque country, characterized by the finely knapped stone ‘leaf points’ of the Solutrean culture (named after a French village called Solutre). Receiving, perhaps, their technologies from north-west Europe, this south-western refuge was culturally distinct from other southern refuges, whose stone technology is described more generally as Epi-Gravettian. The second refuge area was Italy, with more or less continuous local occupation. The third was the Ukraine, a large area north of the Black Sea defined by two great rivers, the Dnepr and the Don, and separated from the rest of Southern Europe by the Carpathian Mountains, which were partially glaciated at the LGM. Two other regions of Central Europe have some claim to small-scale occupation at the LGM. These were western Slovakia, just south of the Carpathians, and the Dnestr River basin of Moldavia, just east of the Carpathians on the north-west coast of the Black Sea.

5

Figure 6.2

European refuges at the LGM. Cold and loss of habitat forced humans down to refuges in south-west France and Spain, Italy and parts of the Balkans, Slovakia and Moldavia. The Ukraine, in Eastern Europe, paradoxically continued to thrive. (Shaded areas show maximum extent of cultures between 15–20,000 years ago.)

The Eastern European sites were home to the final flowering of the Upper Palaeolithic mammoth culture. As the LGM reached its climax, one focus of activity shifted away from western Slovakia, mainly eastward towards Moldavia and the Ukraine, but also south into Hungary. It is in the Ukraine and farther north up the rivers Dnepr and Don into the Russian plain, however, where we find the best record of continuous human occupation – even expansion – in Eastern Europe during the Big Freeze.

6

Genetic continuity and the last glaciation

Can the genetic record tell us more about the ebb and flow of populations in the real human sense of where they

came from

and

went to

, rather than the inferred cultural picture of what they

were doing

, as the cold grip of the ice took hold? Genetic tracing can and does fit the archaeological record of that time rather nicely, but it also tells us something much more relevant and general to European roots: that 80 per cent of modern European lines are essentially derived from ancestors who were present in Europe before the Big Freeze.

In

Chapter 3

we saw how the important European maternal clan

HV spread from Eastern into Northern and Western Europe, perhaps heralding the beginning of the Early Upper Palaeolithic 33,000 years ago. The HV clan is now widespread and fairly evenly distributed in Europe. H is the single, commonest line of all. It was not always so, and a specific sister cluster of the H clan, V, who were probably born in the Basque country, tells us why.

7

The archaeology shows us how the south-western refuge of the Basque country drew cultures and presumably people down from north-west Europe during the lead-up to the LGM. Since Western Europe is separated from Italy by mountains, we would expect the reverse process after the ice age as people re-expanded again from the Basque country and north along the Atlantic coast. This is exactly the picture left by the post-glacial spread of the maternal subgroup V, which has its highest frequency, diversity, and age in the Basque country, falling off as one goes north and only present in rather low frequencies in Italy. V arose in the Basque country shortly after the LGM. Her pre-V ancestor has been dated to 26,400 years ago, long before the LGM. Pre-V is still found farther east in the Balkans and Trans-Caucasus, consistent with her ultimate eastern origin. Even the post-glacial dates of expansion of V (16,300 years in the west) fit this scenario. Exactly the same pattern was seen for the Y-chromosome marker Ruslan, who we saw had moved into northern Europe from the east and found his home in Northern and Western Europe (

Chapter 3

). The present-day picture shows Ruslan at his maximum frequency of 90 per cent in the Spanish Basque country, with the next-highest rates in Western and Northern Europe.

8

Italy, on the other hand, capped as it is by the Alps, was less a refuge for northern populations than a temperate region of continuous occupation by Mediterranean folk present from before the LGM. This is reflected again in the high proportion (over one-third of the total) of persisting preglacial mtDNA lines found in that region. We can see from these examples that the refuge zones are

characterized by dramatic expansions of lines born locally in the refuge zones during the LGM, and also by high rates of persisting lines left over from the preglacial period. The latter pattern is certainly a feature of the Ukraine refuge, which as predicted by the archaeology retains 31 per cent of its preglacial maternal lines. A slightly less convincing case can be made for south-eastern Europe and the Balkans, which retained 24–26 per cent of preglacial lines.

9

I should clarify that just because 20–34 per cent of modern European mtDNA lines have been retained from before the LGM, that does not mean that the rest of the lines found today had to have entered Europe from outside after the LGM. No, they were mostly locals. Of all modern European lines, 55 per cent originated in the period just after the ice age (the Late Upper Palaeolithic) but these, like the V haplogroup, probably derived from pre-existing European lines and simply reflect the post-glacial re-expansions from the refuges – in other words, new shoots off an old stock. Real fresh immigration into Europe from the Near East during the Neolithic period (from 8,000 years ago onwards) perhaps accounts for only 15 per cent of modern lines.

10

An interesting recent discovery about the genetic make-up of the south-eastern European region has to do with Adam’s markers in Romania. The Carpathian Mountains were glaciated at the LGM and thus formed an effective, jagged barrier between south-eastern Europe and the regions bordering the Black Sea. This barrier splits Romania in two from top to bottom. Without their ice, the Carpathians hardly constitute an insurmountable physical barrier today, but they still mark a clear genetic boundary. This is revealed by Y-chromosome markers characteristic of north-eastern Europe and the Ukraine occurring at higher rates to the east of the Carpathians, while the markers more characteristic of Central Europe are found to the west. But this micro-regional boundary is very much obscured by the great dominance of the main Eastern European Y lineage M17, which may characterize the original preglacial

Eastern Gravettian intrusions from the east. This lineage is found at very high rates throughout Eastern Europe – from Poland, through Slovakia and Hungary, to the Ukraine. M17 is still found at high frequencies among the Slavic peoples of the Balkans, which could support the existence of the Balkan ice-age refuge.

11